By Caroline Guay

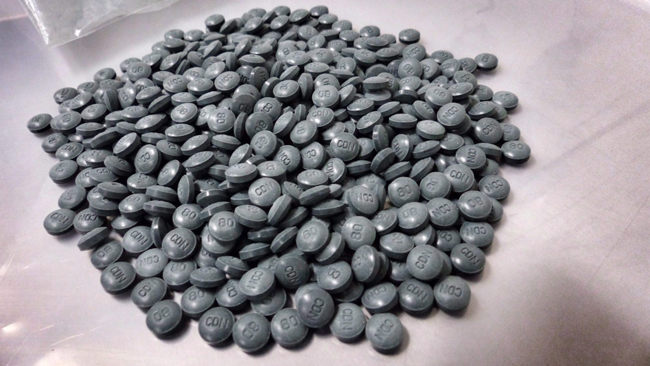

The headlines about the fentanyl crisis are alarming; poisonings caused by this synthetic opioid, which is 100 times more potent than morphine, have claimed hundreds of lives across the country. No longer just a west coast phenomenon, this public health crisis is now in our own backyard; in Montreal, there were 12 deaths caused by fentanyl poisoning in the month of August alone, and more than 90 so far this year (according to CBC news).

Odourless and tasteless, fentanyl is hard to detect, and is often mixed with other drugs, such as cocaine and heroin, without the user’s knowledge. “Traces of fentanyl have even been found in marijuana,” says Doctor Hashana Perera, the Director of McGill’s Student Health Service. “A quantity as small as a grain of salt can kill.”

It’s a sobering reminder that no street drug can ever be considered “safe.” For Dr. Perera, raising awareness of the risks is critical to prevent these poisonings from happening in the first place. “As fentanyl can be present in a variety of recreational drugs without a user intending to take it, disseminating this information to the student population will be a key piece to fentanyl prevention strategies,” said Dr. Perera. “This will allow students to make safer decisions.”

This is why McGill Student Health Service has worked hard to ensure that Naloxone – an opiate antidote – is being made available across campus, and that a broad range of student support staff have been trained to administer it. According to Dr. Perera, security agents, Floor Fellows, Residence Life Managers and the McGill Student Emergency Response Team (MSERT) were trained last week, and training is being organized for Macdonald Campus Security staff and Night Stewards in the days and weeks to come. “All of the groups were very engaged, and everyone is committed to this initiative – it was really nice to see,” said Dr. Perera.

“The Office of Student Life and Learning has generously provided us with the funds to purchase the nasal spray format of Naloxone, which is safer and easier to use,” Dr. Perera said. “We have distributed Naloxone kits to the aforementioned groups and will be monitoring their use.”

Along with the kits, anonymous reporting cards are provided in order to track how, when, and in what circumstances the kits are being used. Names are not required; only the group identification of those involved (for example, “Floor Fellow,” “Security Staff” or “Student”). The card would need to be remitted before another kit is provided to the volunteer.

While volunteers have been trained to administer Naloxone in the case of a poisoning, they are not expected to manage completely on their own. One of the first things they are trained to do is to call 911, as a poisoning victim still needs immediate care after the dose of Naloxone has been administered.

Although the Health Service has been monitoring the spread of fentanyl for the past year and sought to begin the rollout of the Naloxone program earlier, it had to wait until the Quebec government changed the rules to allow non-medical professionals to administer Naloxone.