Under the radar, underappreciated and indispensable: Campus wouldn’t run without McGill’s building directors – and they’re mostly volunteers

By James Martin

McGill’s Facilities Operations and Development unit simply can’t be everywhere at once. That’s where the humble building director (BD) comes in, acting as the on-site eyes and ears for all things brick and mortar. There are 97 BDs across McGill’s two campuses, and most of them are volunteers juggling an unrelated full-time job.

There is no typical BD. Some are profs, while others work in administration. Some of their buildings are dedicated to teaching, some are filled with high-tech research labs. But talk to enough building directors and three common themes emerge: (1) Being a BD is a rewarding gig, despite the fact that (2) their efforts largely go unnoticed unless there’s a problem.

Oh, and: (3) They were bamboozled into accepting the position.

“It’s no big deal.”

“You just have to keep track of the keys.”

“A few hours a month, tops.”

Remember these useful phrases in case you someday need to convince an unwitting colleague to become a BD.

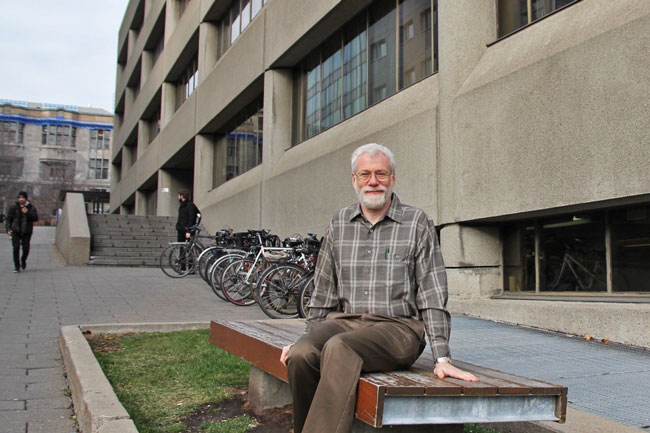

“I got fingered, it’s as simple as that,” recalls Dominic Ryan, a physics prof who does unpaid double-duty as the building director for the Ernest Rutherford Physics Building. “The person who was doing it was going on sabbatical and just needed someone to step in.” Ryan chuckles. “He never came back.” That was more than 20 years ago.

When asked to estimate how many hours of his week are spent doing BD duty, Ryan makes a sound more laughter than number. “There’s always something happening,” says Ryan, who joined McGill in 1986. “This morning, for example, I was dealing with the rebuild we’re doing on the washrooms on the main floor because there’s a leak between the walls that’s affecting the lab below.” His mandate as building director is, to put it charitably, flexible. Although he doesn’t allocate space, or manage construction projects, or oversee safety issues, Ryan regularly weighs in on all those subjects, and more.

“It’s sometimes difficult to avoid having input,” he says. “Or receiving input, depending on your point of view.”

If harsh cold breaks a pipe, as happened last March, Ryan is called in to keep people informed, interface with work crew, dealing with timing on water cuts, re-piped from Administration Building, several water shutdowns, scheduling interventions. Working with the Fire Prevention Office, Ryan organizes and trains a crew of emergency evacuation volunteers. (Those are the people in fluorescent vests you see during a fire drill.) If a construction project requires temporarily cutting the electricity, it falls to Ryan to give notice to everyone in the building – or to push back when he knows that even a brief 6 a.m. blackout could cost a grad student an entire week’s worth of lab experimentation. (It’s happened before.) And whenever a new prof is hired, it inevitably means customizing a lab to fit their specific research needs – considering that half of the Faculty of Science professoriate was hired in the past 10 years, this is not a rare occurrence – and that means Ryan is called into “everything from working out what the researcher needs, design meetings, meetings with project managers, figuring out what makes sense, what doesn’t make sense….”

Rosemary Cooke, too, is familiar with the wide range of BD activities. While working in the McGill Secretariat, she “sort of evolved” into being BD for the James Administration Building. She maintained that sideline for two and a half years, until she became the director of the Faculty of Dentistry. After a brief respite from double-duty, she again assumed the BD mantle in September 2014, when the Faculty moved into its new facilities on three leased floors of a non-McGill building located across the street from the Roddick Gates.

“I got it all,” Cooke says of her time as the James BD. In addition to the core duties – yes, keeping track of keys actually is part of the gig – she received a baptism by fire that included everything short of actual fire. In February 2012, for example, student protestors staged a five-day occupation of some sixth floor offices. (At least she didn’t have to deal with the 2013 broken water main, which caused major flooding to the James and other buildings on lower campus; by then, Cooke had passed the BD baton to colleague Lydia Martone.)

Although building directors are often required to come up with contingency plans on the fly, Cooke explains that a big part of the job is simply educating people about what does, and what does not, fall within the BD purview. “We’re not necessarily responsible for everything in the building,” she says. To aid in this educational outreach effort, here is a pop-quiz. Which of the following items are the responsibility of the building director?

1. Heating? ☐ Yes ☐ No

2. Air conditioning? ☐ Yes ☐ No

3. The microwave in the lunchroom? ☐ Yes ☐ No

Answers:

1. Yes

2. Yes

3. If you even think about saying the words “The microwave’s broken” to a building director, you will get an earful about how equipment is your unit’s responsibility, not the BD’s. And your soup will be cold.

Here’s another pro-tip: Although your Facebook friends may cry “TMI” when it comes to scatological status updates, a BD is cut from different cloth. “I’ve been in buildings where toilets have backed up and nobody said anything because they just assumed that the building director would take care of it,” recalls Cooke. “But if the director doesn’t know, they can’t do anything about it. Too much information is better than not enough.”

“I think the building director role can be misconceived as someone who is in control of a situation,” agrees Donald Nycklass, the associate director of Facilities Management for Student Housing, “whereas they’re really mediating the situation using the information that they have.” Because of the sheer scope of student housing – there are 38 different buildings, ranging from the four large halls overlooking Molson Stadium and the three converted hotel hi-rises to dozens of smaller row houses and apartment-style buildings – Nycklass oversees three full-time, not volunteer, building directors. Their basic concern, however, is the same as any other BD: Keep the infrastructure functioning with minimal inconvenience to the residents.

Nycklass and his team are responsible for controlling who comes into the residences, and giving students ample notice when there will be water and electrical shutdowns or interruptions. (Or, in the case of an extreme interruption, such as the fire that broke out in an upper wing of the Royal Victoria College residence this past February, finding temporary accommodations for displaced students.) Nycklass relies on a mix of hi-tech (Facebook, e-mails) and old-school (putting up posters in elevators, knocking on doors) to get the word out. Considering that, on any given week, there’s some kind construction or maintenance in one of the 35 student residences, there’s always a word to get out.

“It’s not always easy,” says Nycklass. “It’s important to remember that residence is home for the students, so their needs are from six o’clock at night to 10 in the morning – that’s the opposite of when most other buildings on campus are being most heavily used. And, because this is someone’s home, we can’t wait a week for something to turn around. It has to be a same-day or next-day thing. You have to do your thing and fit it in with their thing. It’s not always easy to be the mediator.”

Marilena Cafaro understands those mediation challenges. She is another full-time building director, overseeing the Faculty of Medicine’s 26 buildings. In addition to the big iconic buildings, like McIntyre Medical or the Genome Building, the Faculty works in several repurposed Square Mile mansions, as well as rented facilities in the downtown core.

“The biggest challenges are the continuous maintenance issues, including renovations and different projects,” says Cafaro, a civil engineer who formerly worked as a project manager in the construction industry. Whether it’s a major job like overhauling the McIntyre ventilation system, or routine maintenance, there is always something going on. “If it’s not one building, it’s another,” she says. “When you have contractors in the building at the same time as students and staff, it can be disruptive. That’s the biggest challenge: getting major infrastructure projects done without interrupting studies, teaching and research. It can be pretty hectic. You try to control the noise. If there’s construction going on in the building, and you’re not noticing it every single day, that means things are going smoothly.”

Cafaro notes that the Faculty of Medicine’s many heritage buildings, such as Davis House and Hosmer House (both former private homes now used by Physical and Occupation Therapy) are a double-edged sword: gorgeous buildings that, by dint of their advanced age, require perpetual maintenance. But, as Dominic Ryan can attest, a building need not be a great beauty in order to be a perpetual construction zone. Nobody would rank the Rutherford Building, built in in 1976, among McGill’s architectural gems. “But it’s solid and really functional,” says Ryan, and that means it gets put through its paces.

“It was built at a time when people didn’t worry if the concrete was an inch thicker than it needed to be,” he says. “You can put a couple of tonnes on a few square feet on any floor in the building.” A solid building is particularly necessary when your residents’ stock-in-trade includes things like two-tonne electromagnets, or ultra-high vacuum systems, or huge optical tables. Or when the only way to fit an oversize dilution fridge into a basement lab is to dig a 12-foot hole through the floor and the bedrock beneath the building. “It works,” he says. “And you can do a lot in a building that works.”

It is exactly those kinds of projects, says Ryan, which benefit from having an on-site building director. “Being a faculty member, although it sucks time, means I can interface effectively between the researcher, who needs a lab renovation, and Facilities, who are understandably trying to avoid spending too much money on lab renovations. I have some understanding of the science involved, so if someone proposes cutting a certain corner, I can say, ‘That might not look important, but it is important.’ I know everyone, so I have a good sense of what matters.”

That kind of engagement is also important to Rosemary Cooke. Just as the new Dentistry facilities were designed to bring people together by combining classrooms, clinics and social outreach under one roof, she finds that her BD duties help her to be even more engaged with students and staff in a way she doesn’t get from her “general budgeting and HR stuff” duties as director.

“It keeps me in touch with everything going on in the faculty,” she says. “That’s helpful, because the further up you go, the more you get disconnected – and you have to keep that connection. Before this, I used to run the CFI program and worked closely with the researchers. I really enjoyed seeing what they were doing, so this also kept me in touch.”

“I keep doing it because I can’t get out of it!” quips Ryan. “At this stage, I feel like I’m doing something useful because I have a lot of information I can bring to bear. There a lot of people in facilities and operations and construction that I know well and work well with. Tony Vacarro’s group [Building Operations, Facilities Management and Ancillary Services] are a great group to work with. I can pick up the phone and say, ‘Right, I’ve got this problem…’

“Solving problems is fun,” he adds. “Dealing with blocked toilets is not fun.”