One of the essential, though sometimes under-appreciated, tasks for researchers is to disseminate their work and expertise to a larger audience – whether it be through traditional or social media. In Quebec, the ability to communicate in both official languages only broadens that potential audience.

Speaking French also enhances collaboration – especially outside of Montreal – by opening the doors to numerous professional opportunities.

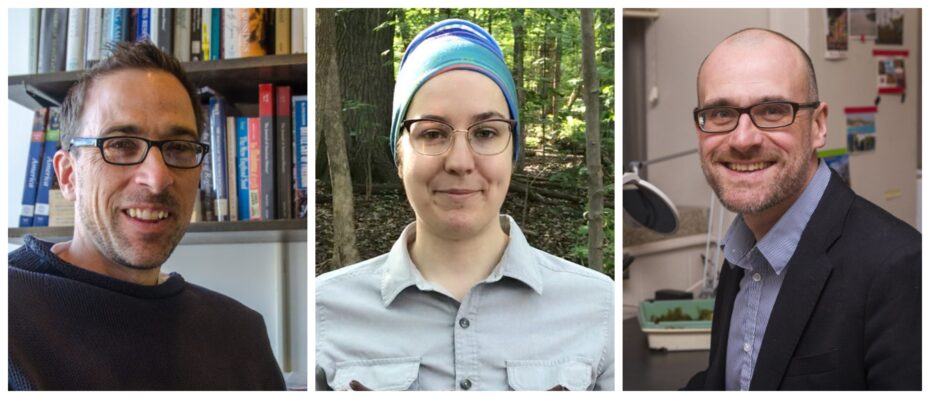

Kirsten Crandall, Andrew Gonzalez and Jason Opal are three McGill researchers who are using French to enhance and disseminate their work. All three are anglophones who took very different paths in learning to speak French. But today, all three are reaping the benefits of being bilingual.

Andrew Gonzalez: Biologist adapts to new environments

Born in London, Andrew Gonzalez grew up in Kent, in the southeast of England. “It is a beautiful part of the world that is often called the Garden of England,” says Gonzalez, the Liber Ero Chair in Conservation Biology. “It was a perfect environment for a budding biologist.”

On top of benefitting from Kent’s fertile landscape, Gonzalez also profited from a home life that was equally stimulating.

“Almost everyone in my family is a language teacher. So, everyone speaks three languages or more,” he says. “My father is Spanish and my mother is English. When they met their common language was French, so I grew up hearing my parents speaking French to each other at home, even though they spoke English to me. As a child, that home environment trained my ear for French and gave me a head start at school.”

Immersive experience

After earning his PhD at Imperial College in London, Gonzalez took a teaching position at the University of Paris VI. Calling it a “severe test” of his French, Gonzalez had to prepare lectures in ecology and evolution to undergraduates.

“I plunged into learning the technical and scientific terms of my field and learned to prepare good presentations in French. Those first lectures were terrifying because nothing prepares you for that experience,” he says. “It was a steep learning curve but within a few months, I had enormously enriched my understanding of French, the skills required to teach science in French, and how to communicate well with the students who also wanted an approachable professor.”

Commentator on issues of biodiversity

Gonzalez came to McGill in 2003. As with any move of that scope, there were adaptations to be made. Nineteen years later, the process is still ongoing.

“When I moved to Quebec, I had to quickly adapt my French; that meant adapting my ear to an unfamiliar Quebec accent, and sometimes a new vocabulary, when working with representatives of the ministries of the Quebec government, town mayors, or when working with conservation NGOs and other organizations wanting to work with me as a biodiversity scientist,” he says. “I am still learning to do this well. I would say that I still miss references that are associated with common idioms or sayings.”

Gonzalez is regularly called upon to comment on news related to the biodiversity crisis. “During my time at McGill, I have had the opportunities to speak about science on French radio (RDI) or TV or speak to journalists writing for French-language newspapers, such as Le Devoir or La Presse,” he says. “Here the challenge is to speak in plain terms and remove the technical jargon that can sometimes get in the way of the fascinating, or terrifying, discovery that the research has revealed.”

Most recently, on March 3, L’actualité published an interview with Gonzalez on the challenges of protecting biodiversity.

Use it or lose it

Gonzalez says the key for anyone looking to learn French, or any language, is to use it regularly and in as many different contexts as possible.

“I liked to listen to the radio, or watch my favorite movies in French. Finding a willing francophone friend to force you out of your comfort zone, both with your spoken and written French also helps,” he says. “At one point, I translated several chapters of Darwin’s On the Origin of the Species from French back to English, to expose myself to the challenge of translation. Learning this way can be hard, and progress can feel slow. But, I found that my learning proceeded in jumps, both in ability and confidence. In the end, it was the diversity of learning experiences and communication opportunities that transformed my ability to work in French.”

Kirsten Crandall: Bilingualism enhances opportunities

The field of biology is challenging enough without having to learn scientific terms in another language. But for PhD student Kirsten Crandall, the extra effort to learn to speak the language of a biologist in French is not just a luxury, but a necessity.

“A lot of my research happens outside of the island of Montreal, and as you go further away from the island, you begin to realize there aren’t as many anglophones,” Crandall said. “If I remained on the island of Montreal and I only spoke one language, my opportunities would be far more limited.”

Early exposure to French

Crandall – a joint PhD candidate in Biology at McGill and at the University of Ottawa – grew up in an English-speaking household on Montreal’s mostly anglophone West Island, as well as the mostly francophone suburb of Vaudreuil-Dorion. Crandall was functionally bilingual since her preschool days, having had the opportunity to take many of her elementary, high school and CEGEP classes in French.

“I went to a private school which focused on doing specifically a 50/50 day of French and English,” Crandall said. “From kindergarten to grade six, it was 50 per cent English, 50 per cent French, and then afterwards, you pick the extent of how much French you’d like to keep in your curriculum.”

While she did bachelor’s and master’s studies at McGill, her course work was mainly done in English, though when she became a PhD student, she began working with French-speaking environmental groups and private companies.

“I was working with a lot of people who spoke only French, or who were bilingual and preferred to be spoken to a written in French, and so that’s sort of where it came back into my research at my work,” Crandall said.

Opening doors

At that time, she also understood the importance of becoming more comfortable with talking biology in French.

“Most of the places that I would look for in a future career are going to be in a mainly French domain,” she said. “I saw that it would be very beneficial for me to start learning all the French terms, and also just being a lot more comfortable with describing my research in both languages.”

Using French on a daily basis, both at home and at work, has not only helped her build confidence, but has opened doors that would otherwise be closed to her.

“If I wanted a government job within Quebec, but I didn’t know French, I wouldn’t be able to have that job because it’s a requirement,” Crandall said. “Same thing for the Canadian government. You have to be bilingual. I knew that if I was most likely going to be staying here long term, which is probably the case, that if I want to make sure I have as many opportunities as possible, I definitely should pursue strengthening my French in order to make sure it’s the best it can possibly be.”

Jason Opal: All in

Unlike either Gonzalez or Crandall, Jason Opal learned French relatively late in life. In 2009, Opalwas living in Maine with his wife when he was hired by McGill. He started taking French lessons right away.

“I was coming to McGill with tenure, and my wife was pregnant with our first child, who I knew would be going to school in French. It seemed to me essential to learn French for the long-term – just for living. I didn’t think of it in terms of scholarship, I thought of it in terms of my kid’s school, speaking to my neighbours, getting the car fixed kind of thing,” says Opal, an associate professor in the Department of History. “For me my initial motivation was family oriented and it grew outward. I didn’t want to be isolated here. I know you can do it, but I wanted to be comfortable where I lived.”

“I was 33 or 34 at the time and I had grown up as an army brat (my father was a doctor in the army) in the U.S. where a second language is pretty perfunctory. Learning French was a major challenge.”

In the classroom as a teacher and a student

Arriving in Montreal in 2009, Opal redoubled his efforts. On top of his duties as a new professor, he took French classes at McGill, hired a tutor, and studied at least an hour every night. “I was all in,” he recalls. “I listened to French music while reading the lyrics and I annoyed my colleagues to write emails in French. I did everything I could.”

Slowly, the hard work began to pay off. Within two years, Opal was asked to be on a dissertation committee where all the meetings were in French. “I was over my head for another year after that,” he says. “But that’s how you learn, right? You have to be just a little bit under water.”

The real turning point came in 2014, when Opal, his wife and his two children spent the summer in Paris while their home underwent renovations.

“In Montreal, you are surrounded by French, but in Paris you are immersed. But by the end of our stay I was [no longer self-conscious about making grammatical errors],” he says. “I think it is tough for academics. We don’t want to make mistakes. But the point is, you have to communicate. You don’t have to be Molière, you just have to communicate well – and people really appreciate the effort.”

“A million ways French has enhanced our life here”

Not only do francophones appreciate Opal’s efforts, they seek out his expertise. In particular, during the last U.S. election, Opal was a frequent media commentator – including on French TV and radio.

As well, it has enhanced his outreach activities. Until the onset of the pandemic, Opal spoke regularly at a francophone CEGEP. Discussing his research in what he calls “my schoolboy French,” Opal says “it opened McGill as a possibility to francophone students. Some of them would email me afterward asking about application process.”

But the biggest payoff to learning French has been at home. “There are a million ways it has enhanced our life here. But, the most dramatic is with our kids,” he says. “Both our children are going to school in French and it has been a real confidence boost for them. It has been such a great opportunity for us to be bilingual. It is hard to imagine our lives if we didn’t speak French.”