The Arctic: the vast space at the Earth’s summit that strikes the imagination with its breathtaking views and legendary animals like the polar bear. The Arctic is also an inhabited space and has been home to a host of indigenous peoples for thousands of years. Today, it is home to almost four million habitants representing a very diverse population.

For some years, though, the Arctic Ocean has been the topic of discussion everywhere because of the unprecedented changes taking place there. In fact, global warming is occurring in the Arctic at an accelerated pace, resulting in a multitude of physical, ecological and social consequences. The ecological impacts have social repercussions and vice-versa. For example, the loss of the sea ice cover can affect the migrations and movements of whales, which, in turn, could make it more difficult for Inuit hunters to track them. The melting of the ice cover could also lead to greater marine productivity and, consequently, to more abundant fisheries.

The region is also seeing an industrial boom as more industries yearn to get their hands on heretofore untapped resources. While there are economic spin-offs associated with these activities, there is also the risk of oil or gasoline spills, as well as the threat of chemical and noise pollution.

Wide-spread impact

All these social-ecological changes have major ramifications for the communities in the Arctic that depend on and benefit from the native ecosystems in numerous ways, be it for the food (fishing, hunting, picking of plants and berries), the water or intangible aspects such as identity and culture. The benefits that humans derive from nature are known as ecosystem services.

All humans also benefit from the Arctic, sometimes without even realizing it. For example, the permanent ice cover of the Arctic Ocean produces a cooling effect that helps regulate the global climate. The loss of this cover will, therefore, have ramifications worldwide.

Adapting and building resilience to the changes in the Arctic require an understanding of the mechanisms involved, particularly the social-ecological relationships through which impacts of a physical or ecological nature have social repercussions. Studying social-ecological dynamics is no easy task and requires reconciling disciplines that often operate in a vacuum, such as biology and ethnography.

Collaborative research

This was the challenge that I set for myself in undertaking my doctorate. The objective of my doctorate was to study how the Arctic marine ecosystem is changing and what the ramifications – current and future – are for the coastal communities.

My focus was ecosystem services, with a view to establishing a connection between ecological and social changes. My research was confined to the Kitikmeot region of Nunavut, where the population is primarily Inuit (90 per cent) and growing (50 per cent of the population is under 25 years). My ultimate objective was to make recommendations for the sustainable management of this rapidly changing marine region of the Canadian Arctic.

Since the very nature of my research was interdisciplinary, my project combined different methodologies and types of knowledge, ranging from biological sampling to interviewing local fishermen and Inuit Elders. My research was done collaboratively so as to address local concerns and incorporate local knowledge.

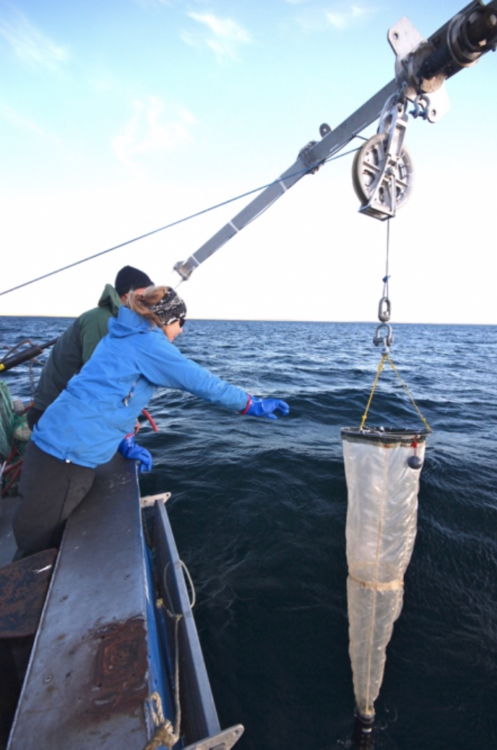

When I began my doctorate, the R/V Martin Bergmann was the vessel from which I started collecting samples in order to study the marine ecosystem. It served as my on-board scientific research platform for the collection of zooplankton, those microscopic animals that, on their own, have a biomass far greater than whales across the oceans. In the summer, Arctic char feed extensively on the zooplankton and the samples I collected helped me to investigate how lower levels in the marine food web influence affect the Arctic char fisheries.

My doctorate experience went beyond just doing research. I established connections with the local residents by taking the time, over the years, to cultivate relationships within the community built on trust. This picture shows some of the traditional foods, of which I was able to partake, including caribou stew, musk ox chili, grilled fillet of Arctic char, maktaak (fresh narwhal, bottom right) and bannock, the traditional bread. This photo at left is of the traditional meal we organized for the participatory workshop.

I left Cambridge Bay in February 2019, with a heavy heart after my last visit as part of my doctorate. After working closely with the community for four years, I realized that I had been on my own journey. Studying the changes in the Arctic was transformative for me personally. Learning to look at my research problems through the lens of the regional inhabitants and from a reality and knowledge base different from my own gave me new insights. Like the importance of reviving Inuit culture to better protect the environment and seeing how inextricably linked the two are.

I came to appreciate the incredible resilience of the people and the value of speaking with the Inuit Elders to understand the resilience of the past in order to better strike a path of resilience in the future. I am extremely grateful to the people of Cambridge Bay for opening their doors to me. Thank you. Quanaqutin!

Read the public report prepared by Marianne Falardeau

Watch the short film Hivunikhavut – Our Future produced by Falardeau that looks ahead to the future of the Kitikmeot Marine Region of Nunavut by 2050.