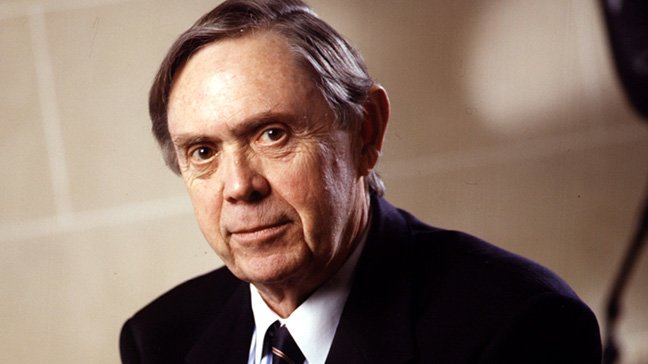

You may be familiar with Donald Johnston (BCL ’58, BA’60, LLD’03) as a former cabinet minister, President of the Liberal Party of Canada, and Secretary-General of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in Paris, or a founding partner of law firm Heenan Blaikie.

Friday, October 18 and Saturday, October 19, offer unique opportunities to hear Johnston as a musical composer – his piece Montreal Montréal has been arranged for the McGill Symphony Orchestra by Marc Beaulieu (BMus ’80, MMus ’97), who adapted and expanded an earlier setting for piano and string quartet by Rafael Zaldivar (MMus ’10, DMus ‘17).

In advance of the concert, we sat down with Johnston to discuss his history in music, friendship with Leonard Cohen, and more.

How did your relationship with music start? Do you have a first musical memory?

When I was young, I was brought up on a small farm in the Ottawa Valley during the War. We had a small piano that my mother played, so I became accustomed to listening to the piano. She learned to play because that’s what entertainment was back in her day – when people sat down in the evening, they often listened to music played by a family member.

I didn’t really take serious piano lessons, except maybe for a couple of years when I was eight or nine years old. It was really when I was getting into high school in Montreal when I started to try to play by ear – basically all my playing is sort of spontaneous from ear. For example, I could read the music when I started playing because it was only within one octave – I’m always impressed with these people who can read scores for the first time!

What role did music play during your later life in politics and law?

Music has been an important part of my life, but not even as much in terms of concert-going and listening to recordings. It’s really just from playing the piano when I could – I think the piano has been very useful for me in terms of bringing people together.

When I went to Parliament in Ottawa, I brought my old Heintzman upright piano into my office. People would come in and we’d sing songs – one of them that came in was a woman that was very important in the Office of the Prime Minister, I think her name was Jane Heintzman. One day, I asked if she was related to the Heintzman family that used to manufacture pianos, which she confirmed! I told her about the piano in my office and said she had to come hear it.

I brought that same piano to the Bank of Commerce building when I worked there, and also brought it to France when I went to work at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). I would have people come in for receptions, and I found several people who were great piano players. You can cross party lines with music!

I once had very senior Russian politicians over at my home in France because Russia was interested in joining the OECD. They were very musical – they sang all these old Russians songs. I had practiced many of these tunes so I could play piano along with my guests! In Paris, whenever I had people from different countries there, if they were interested, we would all play or sing different songs. Waltzing Matilda for the Australians, Wonderful Copenhagen for the Danes…

Even when I was campaigning, I was often playing piano. I would try to play regional songs at different events. People find when they start a leadership contest, you want to try to identify with every region that you go to.

How did your piece Montreal, Montréal come to be?

Montreal Montréal is something I wrote when I was much engaged as a lawyer in the film industry, representing Paul Almond, Genevieve Bujold, and others. In fact, I was a co-executive producer on Oliver Stone’s first film called Seizure. Terrible film, but I have a credit on there anyway!

Paul and I used to talk a lot about film. My recollection is that Paul was working on a film with a North African theme, so I sat down at the piano one day and started to come up with what I thought would be appropriate music for that. I wanted the music to have excitement, be in a minor key and have rather Eastern European and Russian elements – that’s my vision of North Africa. I had someone write down the melody on paper, but because the film didn’t go ahead and I soon went away to Parliament and later to the OECD in Paris, the piece just sat there.

Much later, when I was cleaning out my piano bench in Paris, I found it. I started to play it and the word “Montreal” jumped into my head – I could hear it in the end of some phrases in the melody.

What was it like hearing your piece arranged for the first time?

I found that it captured the mood that I had in mind. The first time it was arranged at McGill was for a goodbye concert for former principal Heather Monroe-Blum. Pianist Rafael Zaldivar [MMus ’10, DMus ‘17] had done an arrangement of the piece to feature himself and Baptiste Rodrigues [DMus ‘13], the Golden Violin winner in 2012 – after the concert, the string quartet that was also playing at the event came up to me and said they’d also like to perform the piece! It took us a while to get that put together, maybe even a year, but we recorded an arrangement of the piece for piano and string quartet in 2014 in the Music Multimedia Room at the Schulich School of Music.

Montreal Montréal was also played in Toronto by a string orchestra called Strings Attached under direction of Ric Giorgi, during a concert at the University of Toronto’s George Ignatieff Theatre. I liked it, but thought there might be some opportunity for brass there too, especially in the bridge. So, I’m excited to hear the orchestral version and see what arranger Marc Beaulieu [BMus ’80, MMus ’97] has done with it. The concert will be my first time hearing this version, but I’ve heard that it sounds quite good!

How did you and Leonard Cohen come to meet?

He and I shared an apartment upstairs from a café on Stanley Street called the Riviera. Afterwards, we stayed in touch once or twice a year by email, even though I didn’t get to see a lot of him.

In 2016, I read about Leonard being ill. I sent him a note and first of all, I got a bounce-back because he had stopped the tour that he was on. After a bit of correspondence, I sent him another note reminding him of our days on Stanley Street in Montreal, and also attached some of my music. It was the recording Montreal Montréal with Zaldivar on piano and Rodrigues on violin.

He wrote back a message that I found very touching, saying “I was able to listen to Montreal, that’s one hell of a piece of music! I didn’t know you were a composer!” That was almost the last I heard from him. That message was from August 30, and he died later that year in early November.

The thing that impressed me so much about Leonard is that wherever I went in France, they knew about him. Also, I discovered that the concert he gave in Slovenia a few years ago was the highest attended concert in the country for the whole year. His music is also generational – when I go to some of the hip-hop stuff, I don’t see many people my age, but at Leonard’s concerts I would!

Thanks to your efforts, Schulich has started a fundraising campaign to help finance the purchase of musical scores for their instrumental and vocal ensembles. Why do you think it’s important for people to support music in universities?

I think it’s very important. I don’t even think we fully understand the significance of music for the human brain, for emotions and everything else. I spoke at a business school in Slovenia several years ago, and the school’s Dean said that they had music as part of their program. They had identified this as helping people learn!

When I started to learn more about McGill’s music faculty as it is today, I was really impressed with it. When I was a student at McGill, I was hardly aware of the music faculty. And now I hear from everybody how good it is. I thought I’d like to help the faculty – I like the people, and there’s great benefactors like Elizabeth Wirth.

Life wouldn’t be very interesting without music. It’s hard to believe how important it is.

Hear the McGill Symphony Orchestra on October 18 and 19 at 7:30 pm. Buy your tickets here.

To donate to the Performance Materials Support Fund, visit the website or call (514) 398-2787.