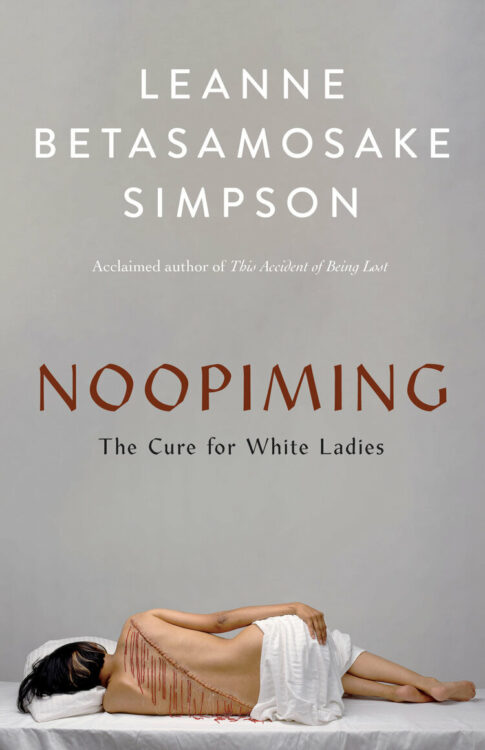

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson has been described by CBC Radio’s Rosanna Deerchild as “a wealth of stories, and ways to tell them.”

Simpson is a Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg scholar, activist, musician, artist and author. Whether she is writing poetry, short stories, essays, novels or songs, the member of Alderville First Nation is regarded as one of the most compelling Indigenous voices of her generation.

In her work, Simpson deals with ideas of Indigenous environmentalisms and land-based knowledge, resurgence and resilience, and Indigenous futurities. She holds a PhD from the University of Manitoba and currently teaches at Dechinta Centre for Research and Learning.

This semester, Simpson will bring that incredible voice to McGill as the inaugural Mellon Indigenous Writer in Residence.

Promoting Indigenous scholarship and community building

The Writer in Residence program is one of the initiatives funded by the five-year US$1.25-million grant by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation in June 2019 to support McGill’s Indigenous Studies and Community Engagement Initiative (ISCEI). The ISCEI promotes the growth of the Indigenous Studies Program in the Faculty of Arts, and aims to serve as a nexus for Indigenous scholarship and community-building and to facilitate communication and collaboration both across units at McGill, as well as in partnership with Indigenous communities.

This semester also marks the launch of the Mellon Indigenous Artist in Residence program, featuring Caroline Monnet, an Algonquin-French multidisciplinary artist from Outaouais, Quebec.

“This is the inaugural year for the new annual Mellon Indigenous Artist- and Writer-in-Residence programs supported by the grant,” says Jessica Coon, Associate Professor of Linguistics and Director of the ISCEI. “These programs bring creative professionals to McGill to share their expertise, engage with students and faculty members, and to increase knowledge of and exposure to Indigenous art and writing among the campus community and the general public. We are excited to be able to launch these programs despite the challenges of being online, and are so honoured that Caroline Monnet and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson will be joining our community this semester.”

“While COVID delayed the Mellon Indigenous Writer in Residence program by a year, we are lucky to have Leanne Betasamosake Simpson bringing her insights into the power of art and storytelling at this culturally and historically fragile time, and thrilled that she is initiating the residency program,” says Tabitha Sparks, Associate Professor, Department of English, and Associate Dean, Research and Graduate Studies, Faculty of Arts.

Prior to her beginning as Mellon Indigenous Writer in Residence, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson spoke with the Reporter.

You are the inaugural ISCEI Writer in Residence. How important is it for McGill – and other institutions – to have initiatives like this?

It is very important right now for universities to support the Black and Indigenous faculty, staff and students they currently have, and it is also very important to be hiring more permanent Black and Indigenous faculty across disciplines and providing them with the support and influence they need to make systemic changes that will enhance research and learning for students. Artistic practice, including writers also contribute to knowledge production and so having positions like Writers and Artists in Residence not only support individual artists particularly in pandemic times, but also enhance the academic environment with different forms of knowledge and practice.

What do you hope to accomplish during your residency?

I have an up-coming book deadline for a co-written project with Robyn Maynard called Rehearsals for Living: Conversations on Abolition and Anti-Colonialism. I will be working on that project during my residency.

You are a writer, a poet and a musician. Do you have a preference or a facility for specific genre? Or is it a question of you preferring a specific genre to express or explore specific subjects?

Genres don’t make a lot of sense to me. In many ways, the themes I explore in my academic work are the same themes that I explore in fiction and performance. Genres, like disciplines, are rooted in western thought and practices. My body of work comes from a different place, and I want my creative and intellectual thinking to do different work in the world.

Could you expand a bit on this and tell us more about that “different place” from which your writing comes? As well, could you tell us more about the “different work” you want your work to do in the world?

The spine of my practice is the land, and Michi Saagiig land-based practices. That is a very generative space for me whether I’m doing academic or creative work. Nishnaabeg intellectual and storytelling practices don’t conform to western disciplines or literary genres. Our world, and our knowledge is organized differently. Ethically and politically, this is my first concern.

I recently watched Dionne Brand’s NFB documentary where she is in conversation with poet Adrienne Rich. Brand talks about writing to her people. I think there is something similar in my work – I write to and for Nishnaabeg and Indigenous peoples first. Of course, non-Indigenous audiences are welcome to read and engage as well, but this sets up a different writing and a different reading experience. My work refuses, rejects and critiques, but at the same time I hope it gives glimpses of how to live otherwise, and how to build otherwise.

Are there recurring themes or overarching topics in the stories you tell?

I think most of my work in one way or another interrogates or perhaps refuses colonialism, heteropatriarchy and capitalism. There are themes of reciprocity, relationality, world building, flight and fugitivity in my work. I am most concerned and interested in the present.

Writers are often told to “write what you know.” How much do your own personal experiences inform your writing?

Personal experience is one source of information amongst many. I like to layer meaning which requires a layering of knowledge. Oftentimes personal experience might be the original source of inspiration, but that leads to research or imaginings, or thinking through things with other writers, artists and thinkers.

Have you always been drawn toward writing? Was there a specific moment when you knew you wanted to be a full-time writer?

Writing is one of the things I’m drawn to, but it certainly isn’t the only thing. It is exceedingly difficult for Black and Indigenous writers to be full time writers in Canada, and so like a lot of other writers, I do a lot of other things – like teaching, for instance to pay the bills. Stories and storytelling have always been very precious to me. Stories have most often brought me joy, meaning and insight. I think I hold storytelling and oral practice very close to my heart.

Do you have any mentors or people who inspired you to follow this path? Any other writers in your family?

My family is a family of storytellers. I’ve had lots of people of all ages who have supported and encouraged me in my life, and I think that’s actually been more important to me than actual mentors.

Do you work on one project at a time or do you have several going at the same time? What projects are you working on at present?

I generally have several things going on in my life at the same time. In writing, particularly if it is a longer form project, I generally only generate new writing on one project at a time. I may be editing, or doing research for another project, but I find it difficult to generate multiple new works at once.

I understand that you are quite concerned with promoting other Indigenous writers and their works. How would you describe the Indigenous literary landscape at present and are there specific writers you would recommend? Why is it important for people to read more Indigenous writers?

The Indigenous literary landscape has really come into itself in the past few years, with writers winning major literary awards, putting their books out with big publishing companies and having a presence at Writers festivals and in the literary world. Queer and Trans Indigenous writers have really produced a powerful body of work in the past few years, and Indigenous writing has much more visibility than it did when I started writing. This year, I found Christa Couture’s How to Lose Everything moving and insightful, as is Mojave poet Natalie Diaz’s Postcolonial Love Poem.

Black writers are also really gifting us with some amazing works right now. I really loved emerging poet Junie Désil’s eat salt | gaze at the ocean. Black Writers Matter, edited by Whitney French is also a terrific read, as is Until We Are Free: Reflections on Black Lives Matter in Canada edited by Rodney Diverlus, Sandy Hudson and Syrus Marcus Ware.

Learn more about Leanne Betasamosake Simpson and her work online. She will deliver an online lecture titled A Short History of the Blockade: Beavers, Affirmation and Generative Refusal on February 4, at 10 am. Get more details and register online.