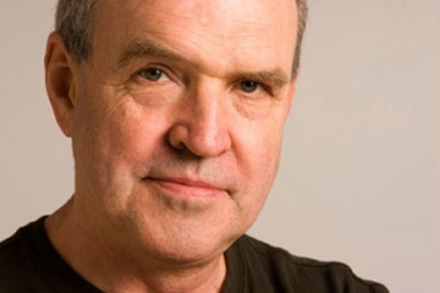

On Saturday, Oct. 19, well-known writer and architecture critic, Witold Rybczynski (BArch’66, MArch’72, DSc’02) will deliver the 2013 Beatty Memorial Lecture.

On Saturday, Oct. 19, well-known writer and architecture critic, Witold Rybczynski (BArch’66, MArch’72, DSc’02) will deliver the 2013 Beatty Memorial Lecture.

In the lecture, titled Architecture and the Passage of History, Rybczynski explores the intimate but unusual relationship between architects and the past. He shows how – and especially why – architecture since the Renaissance has been characterized by recurring historic revivals. Using examples of work by contemporary Canadian architects, he demonstrates how even modernist architects cannot avoid connecting with the past, and why this is a good thing.

A two-time McGill graduate, Rybczynski is the author of such celebrated books as Home, The Most Beautiful House in the World, and a biography of Frederick Law Olmsted, A Clearing in the Distance, for which he was awarded the J. Anthony Lukas Prize. In 2007, he received the Vincent J. Scully Prize from the National Building Museum. He lives in Philadelphia, where he is professor emeritus at the University of Pennsylvania. Rybczynski’s most recent book How Architecture Works: A Humanist’s Toolkit (Farrar, Straus & Giroux) was published last week.

In advance of his lecture, Rybczynski spoke to the McGill Reporter about his Beatty Lecture.

The 2013 Beatty Memorial Lecture; Saturday, Oct. 19; 10 a.m. – noon; Pollack Hall (555 Sherbrooke Street West). Admission free but registration is required. Seating is first-come, first-served. For more information, please contact Lorraine Torpy by email or by phone at 514-398-3992, or visit the website.

Your lecture is titled “Architecture and the Passage of History.” Since everything has a history, what makes architecture special?

If you want to see how people dressed in the Roaring Twenties you go to a costume museum, and if you want to see an antique car you go to a car museum, but if you want to see an old building, just walk down the street. Unlike most human artifacts, like dress, or cars, or ocean liners, buildings have extremely long lives, measured in centuries.

We don’t just look at old buildings, we work in them, live in them, study in them; they are not museum pieces but a part of our everyday lives. If we really like a building, we repair and restore it, or carefully adapt it to a new use. Except for a brief moment when it’s brand new, every building becomes a part of history. Thus, every building represents at least two moments in time: the present, when we–the users–experience it, and the past, when it was built. And some buildings also establish links to an even more distant history.

Can you give an example?

Sure. My first freshman class at McGill was Economics 100 with Cyril James in Moyse Hall in 1960. At that point, the Arts Building was more than a hundred years old, so it was both a reminder of the historic origins of the university and an important part of my student life.

The main architectural features of the Arts Building are a lantern and a Doric porch, which are derived from the cupolas of Renaissance domes, and from ancient Greek temples. This interweaving of temporal and cultural connections is what makes architecture so fascinating. Consider the Peace Tower on Parliament Hill in Ottawa. For most Canadians it is a contemporary symbol of our federal government. That’s why it’s on the twenty-dollar bill. At the same time, when it was built in the 1920s, replacing an earlier tower that burnt, it was intended as a World War One memorial – hence the name. Lastly, the tower is designed in the Gothic style, creating an inescapable connection to the clock tower of the Houses of Parliament in Westminster, the model for our political system.

But surely the High Gothic style is just a Victorian relic?

The Canadian Gothic revival, of which the Peace Tower is striking example, lasted from the late 19th to the early 20th century. But Victorian High Gothic was simply one episode in a very long history. Since the Middle Ages, there was never a time when Gothic was completely out of fashion. You can find Gothic revival town halls in Belgium, Gothic palazzos in Venice, Gothic castles in Scotland, and Gothic parish churches everywhere.

In the early 1900s, there were many Gothic skyscrapers, and during the first half of the twentieth century, built Gothic revival buildings universities appeared on Canadian and American campuses. Recently there has been a renewal of Collegiate Gothic at Oxford, Cambridge, and Princeton, and Yale is in the process of building two residential colleges, both Collegiate Gothic.

Are you suggesting that architects should build in historical styles?

Not necessarily, it’s simply one option. But since historic revivals have occurred regularly over the ages, there’s no reason to expect that they won’t continue. The great British architect, James Stirling, once said, “Architects have always looked back in order to go forward.” Sometimes even a glance is enough. In my lecture I describe the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. It’s a thoroughly modern building, but it looks back, literally, across the Rideau Canal at the Gothic revival Parliamentary Library. The Great Hall of the National Gallery is a simplified glass version of a Gothic chapter house, and the exposed structure of the Gallery’s facade faintly recalls Gothic buttresses.

These historical allusions add a rich dimension to the architecture that would not have been there if Moshe Safdie had simply made the National Gallery a glass box. Buildings that dispense with history altogether can be exciting when they are brand new, but a hundred years later, when architectural fashions change, it’s a different story. Not far from the National Gallery is the National Arts Centre, a building of the 1960s, built in the concrete Brutalist style that was then popular among architects. Its design makes no reference to the neighbouring Chateau Laurier nor to the old Union Station, both fine buildings that are redolent with historical memory – fairytale castle, Roman bath. The rather forbidding Arts Centre, on the other hand, makes no reference to anything but to itself. One can only ask: What were they thinking?