Amblyopia, the vision disorder colloquially known as “lazy eye,” has been long thought untreatable in adults. New work at the McGill Vision Research Unit (MVRU), however, shows that magnetic stimulation can temporarily reverse the condition.

Amblyopia is characterized by poor or indistinct vision in an eye that is physically normal. The condition is usually the result of the brain not learning to properly adjust to childhood conditions like strabismus (“crossed eyes”) or anisometropia (unequal refractive power in the right and left eyes). If amblyopia isn’t treated by adolescence, it’s been assumed the visual cortex becomes locked in its “lazy” habits—even when the eye condition itself has been corrected.

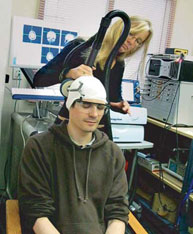

A new study—led by post-doctoral fellow Dr. Benjamin Thompson and MVRU director Dr. Robert Hess—shows that 15 minutes of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), the painless application of rapidly changing magnetic fields to the head, temporarily improved vision in amblyopic eyes. The magnetic fields induce weak electric currents within the brain, which excite neurons in targeted areas. This safe and painless technique has been used to treat Parkinson’s disease, migraines and clinical depression, and to facilitate recovery from stroke. This study marks the first known application of rTMS to amblyopia.

“A very short intervention could improve vision in the amblyopic eye for up to 30 minutes,” Thompson reports. “This suggests that visual loss is not due to loss of brain cells but due to an ongoing suppression of their activity that can be reversed, allowing the potential for rapid recovery of vision.” The team hopes that repeated rTMS treatments may lead to longer-lasting effects. “Our ideas about this age-old problem are currently in rapid transition,” adds Hess, an internationally renowned amblyopia expert. “It was previously believed that treatment of amblyopia in adults was a waste of time.” The results of their study were published in the July 22 issue of the journal Current Biology.

This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR).