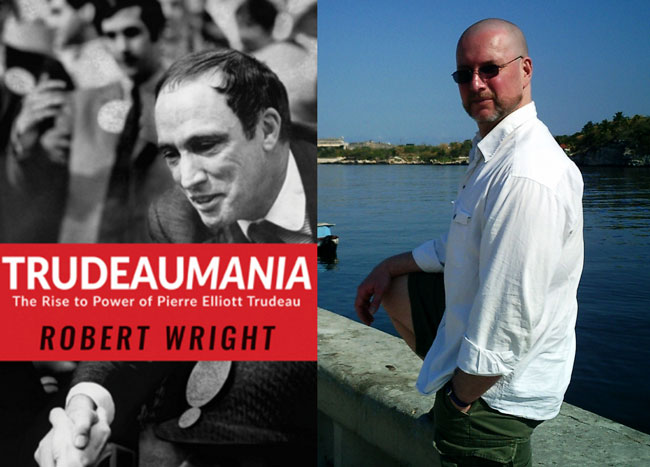

To celebrate the publication of his latest book, Trudeaumania: The Rise to Power of Pierre Elliott Trudeau, historian and bestselling author Robert Wright joins MISC Director, Andrew Potter, for a conversation about Pierre Trudeau and the incredible period leading up to the decisive election of 1968.

In advance of the event, Wright spoke to the McGill Reporter about Pierre Trudeau “the visionary” and compares his rise power to Justin Trudeau’s victory in the 2015 federal election.

The discussion will take place on Oct. 28, from 5 to 7 p.m.; Hotel Omni Mont-Royal (1050 Sherbrooke Street West). Get more information and RSVP to misc.iecm@mcgill.ca.

How did the first incarnation of Trudeaumania in 1968 differ from Trudeaumania 2.0 in 2015?

Well, the main difference is that everyone knew in the spring of 1968 that Trudeau would win the general election, and handily. Liberal Party polls showed him leading with 52 per cent of the popular vote after he won the party leadership, and throughout the campaign his numbers never fell below 45 per cent. So, barring something utterly unforeseen, his victory was a fait accompli. Even his opponents sensed this.

Not so Justin Trudeau in October 2015, when the three main parties were neck and neck just weeks before Canadians went to the polls. For Justin, Trudeaumania broke after the election, as Canadian media sought new narratives for his come-from-behind victory – and, of course, as the outside world discovered that Canada had elected a warm and sexy Gen-Xer bearing the most famous surname in Canadian politics.

What was the public mood like in Canada in 1968?

In a word, anxious – extremely anxious. In less than a decade, Quebec’s Quiet Revolution had completely changed the national conversation about Canada and its future. By the mid-1960s virtually all of Quebec’s nationalist elites – in politics, media, the universities – were advocating a complete overhaul of Canada based on the idea of deux nations. In 1968, the FLQ was in its fifth year of separatist violence. In 1967 René Lévesque had quit the provincial Liberal party to pursue sovereignty-association, and in the fall of 1968 would launch the Parti Québécois.

So by the time Prime Minister Lester Pearson announced his retirement from politics in December 1967, the country was en route to a full-blown national-unity crisis. Trudeau’s campaign team would sloganize his idea of “the just society” but the 1968 election was really about one issue: how many nations is Canada?

What accounts for Pierre Trudeau’s extraordinary appeal in 1968?

Trudeau entered federal politics in 1965 at the age of 46 with the goal of “saving Canada.” It may sound apocryphal but this was the language he actually used. And as one of Quebec’s leading theorists of federalism he carried with him to Ottawa a full-blown program of political and constitutional reform that he had been fine-tuning for well over a decade. Canada was not two nations, he said, but a country of equal citizens and equal provinces. And like all Canadians, French Canadians’ birthright was the whole of Canada, not just the “ghetto” of Quebec. What was needed was a charter of human rights that would protect minority-language rights across Canada and thus take the fuse out of Quebec separatism.

In 1968, Trudeau’s plan to save Canada was enormously appealing to an anxious electorate. Everything, including the hype of Trudeaumania, followed from that. Well before Canadians had fallen for Trudeau’s blue eyes and telegenic smile, in other words, they had fallen for his ideas.

It is has been three decades since Pierre Trudeau retired from public life, yet Canadians still debate his legacy with an unparalleled intensity. Why does he continue to cast such a long shadow over Canadian politics?

I think there are two main reasons. The first is that Pierre Trudeau was a true visionary, which, for better or worse, we seldom see in Canadian politics. Our most successful Canadian prime ministers have tended to govern in a bland managerial style. Think Mackenzie King, Jean Chrétien or even Stephen Harper – successful leaders who led Canada without lofty political philosophies or grandiose dreams. Pierre Trudeau was not like that at all. He was never satisfied merely to manage Canada. As one of his aides said during the 1968 campaign, Trudeau thought Canadian politicians had spent far too much time squabbling about taxes instead of thinking about how to make Canada “a swell place.”

The second reason follows from the first. Pierre Trudeau was, and remains, a polarizing figure. He was beloved by those who shared his lofty ideals, and loathed by those who thought his dashing style smacked of arrogance and managerial incompetence. Today, Pierre Trudeau’s fans take great pride in his achievements, and particularly in the Charter. His critics, meanwhile, fume that we are still cleaning up the mess he left after sixteen years in power.

Oct. 28, from 5 to 7 p.m.; Hotel Omni Mont-Royal (1050 Sherbrooke Street West). Please RSVP to misc.iecm@mcgill.ca