By McGill Reporter Staff

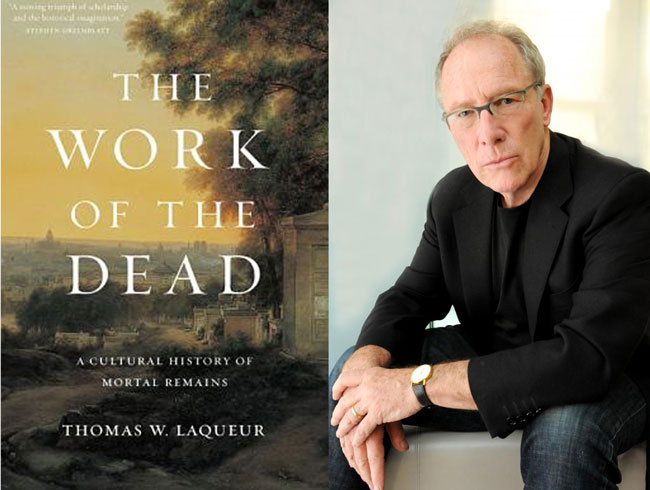

Thomas Laqueur, award-winning historian and author, will deliver the 2017 Cundill Prize Lecture in History on Nov. 15 at 5 p.m. at the Faculty Club (3450 McTavish Street).

Laqueur was the winner of the 2016 Cundill History Prize for his book The Work of the Dead: A Cultural History of Mortal Remains, which offers a compelling and richly detailed account of how and why the living have cared for the dead, from antiquity to the twentieth century. The book draws on a vast range of sources – from mortuary archaeology, medical tracts, letters, songs, poems, and novels to painting and landscapes.

In advance of his lecture, Laqueur spoke to the Reporter about everything from the possibility of people living for 500 years and the changing definition of death through history.

Wednesday, Nov. 15, 5 p.m. Faculty Club (3450 McTavish Street), Leo Yaffe Billiard Room. Get more information about the lecture. Free and open to the public; however, RSVPs are encouraged. Please reserve seating by email.

“When is someone dead?” used to have a clear answer. Now it seems much less so; one can be brain dead but still alive for the purpose of harvesting organs for donation for example. What happened?

Before the eighteenth century, the answer in the west and elsewhere was “when the soul left the body.” The big change when death came to be construed biologically: “when the smallest physiological support of life was gone.” That was the conceptual beginning of our modern way of thinking. Its practical beginning was the advent of the new technologies that sustain the Intensive Care Unit – ventilators, feeding tubes, defibrillators- in the 1960’s. All of these allowed us to maintain the support of life from outside the body so to speak. So now the question is when to stop.

But in a way the most recent definition of death “brain death” – is also very old fashioned. Almost all cultures have held that breath is what makes inert matter live; God breathed life into clay is more or less the story everywhere. Brain death really means that someone is judged, because, of the state of the brain, to be eligible to take a test that shows whether she will ever be able to breath again. If she fails that test she is dead. So the words of King Lear over the body of Cordelia – And thou no breath at all? Oh, thou’lt come no more/Never, never, never, never, never – still express what we understand death to be.

Some biologists are sure that in the not too distant future human life can be greatly extended; 500 years is easily in sight. Assuming they are right about our ability to slow aging dramatically, will living so long fundamentally change what it is to be human?

I believe that being mortal is the fundamental condition of being human. This is what makes it so difficult for us to imagine what an afterlife – at least an embodied afterlife in which we retain our individual corporeal identities – would be like. My guess is that extending life to something like 500 years might make it possible for us to imagine new possibilities – more careers in a lifetime, more books read or movies watched – but we would still be mortal creatures. I suspect that life extension would be a kind of ageing in slow motion. I am not as thrilled as some are by the prospect.

You teach a course about death and dying in historical and contemporary perspective. Why do young people, so far from their own ends, want to take it?

I teach the course with a doctor. Many of our students are pre-meds who realize that they will have to think about end of life issues in their professional lives. But others take it I think as a way of confronting the sorts of big issues that students attend college to confront: the relationship between biology and culture; the differences between secular and religious ways of thinking about death – we have many devout students from many religious traditions; and the meaning of life itself.

Your book is called The Work of the Dead. The title seems absurd; the dead don’t work. What could you possibly mean?

Of course, the dead do not literally work in the sense we learn in a physics book although if you believe, as I don’t that, the revenant can wreak havoc in the world they have purportedly left, then I suppose they can even do that. But still the dead work for us, the living. We need them more than they need us. The history of the work of the dead is a history of how they dwell in us – individually and communally. It is a history of how we imagine them to be, how they give meaning to our lives, how they structure public spaces, politics, and time. It is a history of the imagination, a history of how we invest the dead – the dead body – with meaning. It is really the greatest possible history of the imagination. To be specific, we need the fragments of the dead in the September 11 monument for it to do the cultural work that it does; we visit cemeteries because there are real bodies there. The poet Federico Garcia Lorca once said that “nowhere are the dead more alive than in Spain.” We need not dispute national rankings to get the general point.

This is my take on immortality. As you can see, outlook is more positive. Homo Immortalis Omnipotent Living in “Infinite Space-Time”! No more “human created secondhand God’s”! The function assigned to GOD is now available through understanding the Universe we are part of. We will be the Engineers of our own body chemistry, in the Infinity of Space-Time we can live forever. Biotechnology will control the “aging process” (we don’t wear out, but are DNA programmed to age), and “involuntary death” will not exist any more. Science, Gene Engineering, Nano Technology, Epigenesis, Astrophysics etc. and Extra Terrestrial Migration will allow… Read more »

I believe you when you say that a 500-year lifespan doesn’t thrill you. What rather than bumping 85 years up to 500, what about adding just 10 years? (10 healthy youthful years!) On your 80th birthday, would you gladly take a guarantee of healthy living until age 92? And then, on your 91st birthday, would you turn down the chance to live healthfully until age 110? Now you’re 109. Two choices: 1 more year to live, or 15 more. (again, in perfect health)?

Et cetera.

I, for one, would feel no compunction on accepting all 500 years right now.