Story by James Martin

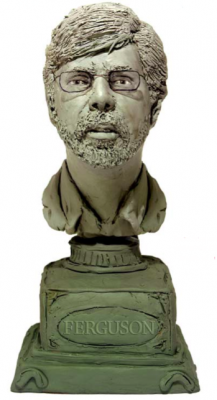

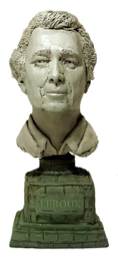

Sculptures by Karen Caldicott

As a vibrant site of traditional artistic practice, you might think the Schulich School of Music is the odd man out in McGill’s research-intensive environment. The school’s composers want to change your tune.

Ludwig van Beethoven loved red wine, long walks and jotting down ideas. His famous sketchbooks — actually collections of some 8,000 loose pages — show how the composer worked out complex musical ideas. But all those semi-legible scribbles weren’t composing, says Sean Ferguson. They were research.

“When you’re actually writing a piece, that’s artistic practice,” says Ferguson, who was appointed dean of McGill’s Schulich School of Music in May 2011. “But the work leading up to writing — developing new strategies and techniques, like the sketches where Beethoven takes a motive and figures out all the ways he can transform it — that’s artistic research.”

The music school is home to eight composers, including Ferguson. Just like their colleagues in the sciences, they often approach musical composition by asking a question. It could be a question about harmony: How can music be written so the audience hears exactly what the composer intends? Or ways to use new technologies: How can sounds be spatially projected over loudspeakers so that concertgoers experience a new immersive virtual environment?

“Compositional research can be contributing to new technology,” says Ferguson. “It can involve psychology and perception. It can be cultural studies. It can be artistic research in the sense of developing new ways of thinking about harmony or form or melody.”

As the former director of McGill’s Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Music Media and Technology (CIRMMT), Ferguson has extensively collaborated with scientists and engineers on projects like the real-time manipulation of instrumental sound in concert or creating new digital instruments that transcend physical limitations. Those high-tech collaborations have given him valuable insights into how other people see composition within the University.

“It’s not always easy for people to understand artistic research,” he says. “One of the things that’s been good for me is collaborating with people outside music. I’ve learned how they see their own work, and the confusions they have in seeing my work. It’s a valid question: ‘You don’t publish your results in Nature, so how do I know what it is?’ Even composers themselves don’t necessarily agree on what constitutes research in their domain. Artistic researchers can look peculiar from the outside, until you put yourself in their position. Sometimes their work looks like science, sometimes like engineering, sometimes the humanities. And sometimes it is completely unique.”

Ferguson’s own research marries musical creation with new technology, and his compositions have been performed by the Philharmonic Orchestra of Radio France, the Montreal Symphony Orchestra, the Société de musique contemporaine du Québec and Les Temps modernes de Lyon, among others. A big part of his work involves computer-assisted composition. Ferguson named his software Apprentice because he likens his interaction with it to that between baroque painters and their skilled helpers.

“The painter would train the apprentice so they wouldn’t have to spend hours painting fabric folds or some other time-intensive detail,” he says. “In the same way, I could play 200 chords on a piano to judge

which ones are the most consonant or I could train an apprentice to do it for me who would then give me a selection of the most suitable ones — but I still have to listen to those chords myself and make the artistic decisions. It does not compose for me. It’s not a shortcut. You can do things compositionally that you couldn’t do otherwise, but it doesn’t make composing faster. It allows me to expand my harmonic language beyond a small repertoire of chords that I return to all the time. It allows for more diversity.

“I could listen to hundreds and hundreds of chords, but it would be exhausting,” he adds, “and after a while they would all start to sound the same!”

Philippe Leroux, who joined the faculty as associate professor of composition in the Department of Music Research in September 2011, is also interested in new technologies. The French composer is world-renowned for his works using live electronics and multi-channel audio. His music has been performed at festivals around the world and he’s received commissions from the French Ministère de la Culture, the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France and Südwestrundfunk Baden-Baden, among others.

One of Leroux’s research interests is in the activity of composition itself. In France, he collaborated with anthropologist Jacques Theureau and musicologist Nicolas Donin on a Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/ Musique project. Theureau and Donin studied Leroux’s every artistic move — for 18 months — while he composed Voi(rex), a piece for a soprano, six instrumentalists and live electronics.

The study broke down Leroux’s creative practice into cognitive ergonomics, from his initial idea to write a voice-centered piece to preparation (making sketches, compiling lists of material, organization), to writing the score, to, finally, tweaking the composition during rehearsals. Leroux is fascinated not only by the insights into his creative process, but by the surprising, nonmusical applications of this knowledge. Jacques Theureau had previously studied nuclear plant security systems, professional ping-pong players and fishermen in Brittany — seemingly strange bedfellows that find common ground in basic processes of human activity — and his work with Leroux was later used to create, of all things, a production protocol for the Renault auto factory.

“It was amazing,” says the composer of this unexpected throughline. “A lot of people don’t think contemporary music is very useful to society — but beyond the artistic benefits it brings it can even be used to make cars!”

Of course, it can be used to make music, too: Leroux used the project’s data to create a new piece, Extended Apocalypsis, which was premiered in autumn of 2011 by the Athelas Sinfonietta in Copenhagen, during the Integra Festival that brought together research centres, ensembles and composers from around the world.

“The first thing for me, always, is to try to compose good music,” says Leroux. “And, at the beginning of the 21st century, to compose good music requires new tools.” To that end, he’s keen to collaborate with researchers in McGill’s Music Technology Area.

“Electronics have changed how we listen to music, and also our composition concepts. Now, for example, we can repeat sounds infinitely. Or we can play much faster than a human could. Or we can change a sound little by little, a slow and imperceptible continual transformation. Those are completely new things. Before, we couldn’t ask a violinist to repeat the same notes for two days. When a sound is infinite, it changes our relationship between music and memory; that has to change our points of reference. It’s interesting to examine that path, to show the possibilities of electronics to extend the instrument’s possibilities — and the instrumentalist’s possibilities.”

Denys Bouliane is also looking to take composition into the future, but not necessarily through technological innovation — or even by looking forward. The associate professor of composition in the Department of Music Research is concerned about what he terms the “symbolic value” (as opposed to market-driven, monetary value) of music. “If we want to prepare for the future, we must give meaning to music,” he insists. “With all the greatest respect to Mahler or Mozart, who I teach very happily, I ask, ‘Why are they great masters?’ How did the form of Mozart’s music represent the political and social ideas of his time? How did Mahler transform the formal structure in his 10 symphonies to reflect the dissolving social order of Vienna?

“Then, for my own work, how can I reformat the musical language to express things in a fresh way — but still communicate with listeners? Universities are one of the few places left where you can think about music in these not necessarily commercial terms.”

Bouliane is preoccupied with questions of cultural identity. As a Québécois who spent half his life in Europe — he was based in Germany for almost 20 years before returning to Quebec — he’s been asking himself difficult questions. “Where do I come from? What do I stand for? Do I have roots anywhere?” Music, naturally, is his main tool of inquiry. But, whereas his German colleagues could draw upon centuries of tradition, Canada’s musical history is short. So he’s inventing his own.

He’s five years into an ambitious project: a nine-opera cycle that tells an alternative history of Canada and North America by speculating on what 500 years of a real crosspollination between First Nations and European culture and music might sound like. In Bouliane’s version, Jacques Cartier and his band of 16th-century explorers landed on the shores of Anticosti Island, located in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, “with an attitude, not to conquer, but to learn.” (In reality, Cartier sailed along Anticosti’s shores in 1534, but doesn’t seem to have ever set foot on it.) The explorers and the island’s Mi’kmaq residents go on to make beautiful music together, figuratively and literally, “while learning to share a fabulous transcendental secret.”

“Of course, in my story everyone’s favourite mode of expression is music,” chuckles Bouliane. He has immersed himself in studying authentic First Nations musical traditions, as well as the Portuguese sailing songs favoured by Cartier’s crew and other European music of the time. Now he’s combining that meticulous research with a deep understanding of how real-life musical evolutions work, to create a “syntactical functioning musical language” that can change as he recounts key moments in the history of his mirror-world. In early 2011, Bouliane achieved an impressive hat trick when the first three instalments of his Anticosti cycle were each given major world premieres. The Montreal Symphony Orchestra, under Kent Nagano, performed Vols et vertiges du Gamache for orchestra with Schulich colleague Matt Haimovitz as cello soloist; the Orchestre Métropolitain, with Yannick Nézet-Séguin, performed Kahseta’s Tekeni-Ahsen ; and Tekeni-Ahsen, for quintet and real-time electronics, was presented during the live@CIRMMT concert series under Bouliane’s baton.

“This hybrid music I’m creating is not about being right,” he says. “It’s my reinterpretation from two different perspectives. The point is to re-evaluate what musical culture is, but without just quoting First Nations music — that wouldn’t be respectful or imaginative.” Instead, he’s thoughtfully intertwining distinct strands of cultural and musical DNA, then growing them in neverheard directions.

“It’s a touchy thing,” he admits. “I don’t like cultural tourism or cafeteria-style picking of elements: ‘Let’s take an Indian drummer, a South African singer and a Montreal jazz player and improvise for an hour.’ That’s not what this is about. I’m trying to take the spirit of rhythms and forms and make them inhabit the work from the inside.” On top of that, he’s extrapolating historical events into a rich fiction that includes an imagined pen-pal correspondence between Jacques Cartier and the French satirist François Rabelais, and a Freemason-worthy conspiracy theory that recasts key historical figures as secret Anticostians. There’s an epic love story, too.

“It’s a crazy, crazy thing,” he admits with a laugh.

“Composers aren’t just the lunatics who dream of a better world,” he adds. “Scientific research is about discovering new things and pushing the boundaries. That’s exactly what we’re trying to do, too: to go where nobody has gone before musically. If everyone in the world did music the same way, by god it would be boring!”

Funding sources for this research include the Canada Foundation for Innovation, the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Société et culture, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Canada Council for the Arts.