By Mark Shainblum

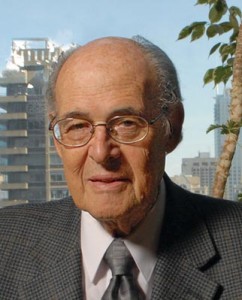

Ronald Melzack is an emeritus professor of psychology at McGill who revolutionized the study and treatment of pain. His historic partnership with Patrick Wall of MIT led to the 1965 publication of the Gate Control Theory of Pain, which overturned the then accepted view of pain as a primitive and static danger warning system. Instead, Melzack and Wall argued that psychological factors and environment play a large role, and that pain is subjective and ultimately at the mercy of the brain. Melzack has been honoured with a Killam Prize and is an Officer of both the Order of Canada and the Order of Quebec. On April 29, 2009, he was inducted into the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame, in recognition of his “outstanding contributions to medical science and the improved health and well-being of people everywhere.” From his office in the Stewart Biology Building, Melzack reflected on his career—and the future of pain relief.

How did you first get interested in the question of pain?

It was an absolute fluke. [McGill psychology professor] Donald Hebb was doing research on dogs raised in relative isolation. He was particularly interested in their problem-solving ability. They were well fed and well looked after, but they didn’t have the life experience a normal dog would have. So when these restricted dogs were let out of their cages, as they were running around, they would sometimes bash into a low-lying water pipe that happened to be in the room. They didn’t make a peep, and I thought, “These dogs don’t seem to be feeling pain normally.” Until then, it never entered my mind that pain should be a field I should look into.

Is that when you started to conclude that the accepted view of pain might be wrong?

That’s right. I began to realize that pain is subjective. You may have an injury, but the injury is not the pain. That became my PhD thesis. I had puppies like Hebb’s specially raised for me, and studied their responses to things like showing them a flaming match. These dogs would stick their noses right into the flame, back off for a minute, and then stick it right back in again. A normal puppy wouldn’t let you near him with a flame, and if he did stick his nose in it once, he’d never do it again!

What did this tell you?

I concluded, after this and a lot of other research on the problem, that our brain selects what comes in and keeps other things out. That’s when the idea of a gate came to me. Let’s say your brain rapidly becomes aware of an interesting stimulus. There are large fibres that move information rapidly up to the brain to indicate that something is going on, while other information moves more slowly. If that information is important, the brain will open the gate to allow it in, and shuts the gate to the unimportant stuff. That’s the gate control theory in a nutshell.

What was the prevailing view of pain when you were starting out?

Actually, it’s still the prevailing view, and one that I have been fighting all my life, that there’s a “pain system.” Common sense says that there are pain receptors in your body, in your skin and viscera, and these receptors have a pain pathway, and you can actually stimulate skin and find the pathway that goes up to somewhere in the cortex, which is supposed to be where we feel pain.

And this is wrong?

At one time it was a good idea, but now it is hindering research. It’s simple and easy to believe, there’s lots of technology, lots of research money, but that research is going nowhere in helping us understand chronic pain. And chronic pain is the real problem.

How did you end up at the University of Oregon after finishing your PhD at McGill in 1954?

I was there for three years, and it had a tremendous impact on me. It was all due to a scientist at McGill named Herbert Jasper, a brilliant neurophysiologist and one of the pioneers of EEG [electroencephalography, a neurological diagnostic procedure]. I told him I wanted to do postdoctoral research and learn more about the brain. After thinking a bit, he told me about his friend, Dr. William K. Livingston, who had an excellent pain laboratory at the University of Oregon Medical School. The lab was small, half the size of this room, but some outstanding people went through there and spent a year or two working with him.

It was Livingston who first introduced you to patients suffering from chronic pain?

Yes, he invited me to come with him to a clinic he and a few other doctors ran every Tuesday afternoon. They saw patients who were in terrible, chronic pain, and tried to do whatever they could to help them. He warned me that there wasn’t a hell of a lot they could do, but they tried. That is when I realized that I had no idea what pain really was. When we think of pain we thing of burning our finger on a hot stove or breaking an ankle skiing. But you know that kind of pain goes away. These patients were suffering terrible chronic pain that basically never stopped.

And that’s when you met the famous Mrs. Hull.

Mrs. Hull had a great impact on me. She was a woman in her late 70s with diabetes. She developed gangrene and had to have both of her legs amputated. I liked her; we talked a lot, her and her marvellous husband Willy. I was a bachelor then, and I would take them for afternoon drives on Sundays, and we became quite friendly. She was a highly intelligent person with a good vocabulary, and I began to collect her descriptive words about pain like “burning,” “shooting,” “crushing,” “horrible” and “excruciating.”

And this was the origin of the McGill Pain Questionnaire, the pain rating scale still in use today?

Yes, from Mrs. Hull and dozens of other patients I began to collect these pain words. I’ll read some of them to you: flickering, quivering, pulsing, throbbing, beating, pounding, boring, drilling, stabbing, lancinating, hot, burning, scalding, searing.Later at MIT, I met the superb statistician Warren Torgerson. He had the statistical techniques to really make this solid. We had 102 words to start with, and we ended up with something like 78. And then we asked people to rank the words: How much pain is implied by a word like “stabbing” or “searing” or “smarting”? It had never been done before.

Tell me about your phantom limb patients.

Mrs. Hull is the most vivid in my memory, but there were many others. We had a woman who had her rectum removed surgically because of cancer, but she still felt it. She had a painful phantom rectum. There were men who lost their genitals and were amazed that they felt phantom erections. One out of three women who’ve had mastectomies feel a phantom breast, though it’s usually not painful. They feel the breast, they even feel that it fills the bra cup. There are phantom everythings: eyes, ears, noses, teeth, you name it!

And that didn’t fit the prevailing theory of pain?

It certainly didn’t. But Livingston and I weren’t alone in this area. Dr. Harry Beecher was a U.S. Army medic during World War II, and he was treating soldiers at the Anzio beachhead. Men with terrible burns and bullet wounds would be brought to him, and he’d offer them morphine, and they’d say, “Doc, I don’t feel any pain, I don’t need it.” Harry and I were very good friends when I was at MIT, and we’d talk about this, but he was still stuck with the idea of the pain pipeline. And I’d tell him it didn’t make sense. How can you say that the guy’s got pain without pain? He said it was pain sensation without pain emotion. My response was: But this man’s got no pain. And what about the people who feel pain but don’t have any physical problem that you can find? We need a new theory. Harry was actually very pleased when the gate control theory came out.

So what does the future hold for pain research and pain control?

The future is research on how the brain creates our world: the world we see, hear, touch and feel. Pain is the doorway into that. I mean, right now, I am just a little upside-down person on the back of your retinas. You don’t see me upside down, or jumping around as your eye jerks around. Your brain creates me. Most people don’t want to hear such a thing. They want to think that what you see is what’s out there.

So it’s all subjective?

Everything is subjective. Everything. But people don’t want to hear that.