UNESCO recognizes what McGill geologists have known for over a century:

The Joggins Fossil Cliffs are a world treasure.

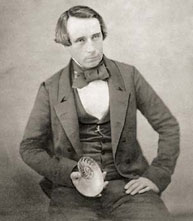

Long before he was principal of McGill University, Sir John William Dawson was a teenage geology buff with an unquenchable curiosity. In the late 1830s the lad ventured into the “remarkable cliffs” of Joggins, Nova Scotia. In his autobiography, Fifty Years of Work in Canada, Dawson recalled that fateful expedition: “I was amazed at the grand succession of stratified beds … and was interested beyond measure in the beds of coal, with all their accompaniments, exposed in the cliffs … and the numerous fossil plants displayed in the beds…. I returned in the evening to the quarrymen’s shanty, thoroughly fatigued, but loaded with fossils, delighted with the knowledge I had acquired, and with my enthusiasm for geology raised to a higher point than ever before.” Over Dawson’s long career, he would return numerous times to the rich area now known as the Joggins Fossil Cliffs.

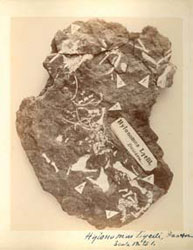

On an 1853 visit to Joggins, Dawson and famed geologist Sir Charles Lyell identified what stands as the oldest known reptile, Hylonomus lyelli, groundbreaking evidence that reptiles, birds and mammals have common ancestry. That discovery, along with a wealth of fossilized amphibians and forests dating from the Carboniferous period (approximately 360 to 286 million years ago), electrified the international scientific community, even earning Joggins a mention in Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. The fossils continue to be studied.

In July 2008, the World Heritage Committee added the Joggins Fossil Cliffs to the list of UNESCO World Natural Heritage Sites. The stretch of coastline is now part of an exclusive club that includes natural wonders like McGill’s Gault Nature Reserve, the Grand Canyon and the Great Barrier Reef. Robert Carroll, curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Redpath Museum and emeritus professor of the Department of Biology, began his extensive research on the Joggins fossils in 1962. His work demonstrated beyond a doubt that Hylonomus was close to the ancestry of both modern reptiles and mammals—providing the primary argument for declaring Joggins a UNESCO world heritage site. Over his decades at McGill, Carroll has led frequent fossil hunts to Joggins, and several of his students have published papers about specimens found there.

“The McGill connection with Joggins is as close today as it was at the time of Dawson,” says Carroll. “And the Joggins fossils remain an extremely important discovery for understanding the evolution of land vertebrates, including the ultimate ancestors of humans.”