McGill researchers are one step closer to fighting bacterial infection—from the inside out.

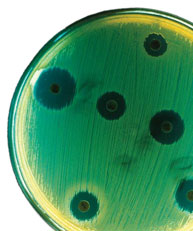

Joint research between McGill and Oxford University uses population evolution and ecology to interpret the spread of bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, dubbed “superbugs” for their tenacity. The team applied the “source-sink” theory to explain how antibiotics and disinfectants are failing in hospitals.

Andrew Gonzalez, Canada Research Chair in Biodiversity and associate professor of biology, explains that certain hospital environments, such as water reservoirs, represent excellent “source” areas for bacteria to thrive. It is the steady supply of bacteria from these source environments that allows them to infect humans. Antibiotics and hygienic practice, however, should make hospitals inhospitable “sinks” for bacteria: More microbes should drain from the “sink” than are replaced from the “source.”

Yet superbugs thrive. The secret to their success: Superbugs need not wait for a fortuitous genetic mutation to adapt to hostile forces like antibiotics. “They can double their population very fast because useful DNA can be transferred quickly in a simple organism,” says Gonzalez.

Within that transferred material, Albert Berghuis, Canada Research Chair in Structural Biology, and his research team in the Departments of Biochemistry and Microbiology & Immunology have observed how one superbug, Staphylococcus aureus, disarms the antibiotic Synercid using an enzyme that detoxifies quinupristin, one of the antibiotic’s component drugs.

“It is only a matter of time before a superbug will be resistant to all antibiotics,” warns Berghuis. His team will focus next on developing a compound to replace quinupristin in Synercid, and explore whether a similar modification in other drugs might further slow bacteria resistance.

“There is a small selection of drugs that still work against superbugs, but bacteria are very resourceful,” says Berghuis. “What we observed is only one trick they use to develop resistance, but if we keep on winning these battles, I think we can stay ahead.”

This research is funded by CIHR and the Canada Research Chairs program.