From May 8 to May 12, twenty-five Members of Parliament (MPs) and parliamentary staff representatives, hailing from nine different countries, attended the McGill School of Continuing Studies (SCS) Parliamentary Residency, to learn and discuss, share ideas, and apply new knowledge towards improving their respective parliaments.

Attending Parliamentary Residence awards MPs and parliamentary staff an opportunity to step back from their daily routine and examine the work they do, tweak certain aspects, and ensure they uphold the high standards of any parliamentary democracy.

People working in parliaments play a pivotal role in a country’s governance system. They oversee the executive branch, represent the electorate, and create laws, all to better serve the people. To perform these critical roles, parliamentarians must be well trained to meet the challenges of the day, to offer a fresh approach to solving problems, whether it is a post-pandemic budget crisis, climate change, or conflicts.

This year’s residency

Strong parliamentary training programs, like the one at SCS help ensure that members and staff will be effective, proactive, and responsive. It offers two programs: one for parliamentary staff and the other focusing on newly elected MPs.

“What I take from these gatherings,” says Sven Clement (MP, Luxembourg) “is seeing how different we are and yet we are fighting for the same goal. I find that always very refreshing and encouraging. Having these cross-party, cross-national meetings enables us to see that we are not alone. We become better individually through collective wisdom.”

In parallel to this year’s residency, ten research team meetings were held which included several international instructors and McGill research assistants. Ongoing discussions were held throughout the week revolving around the most recent research projects – Developing an Expanded African Parliamentary Index, Parliamentary Oversight of Public Financial Management in Small Jurisdictions, and Parliamentary Oversight of the Explosion in Post-COVID Canadian Government Spending and Debt.

The first parliamentary residency was held at McGill in 2012 and every subsequent year, except 2020-22, when, due to COVID, it was held virtually. In addition to McGill, residency courses have been offered in Abuja (Nigeria) in 2014 and once in Naivasha (Kenya) in 2018, thanks to two of McGill’s partners – The Nigerian Institute for Legislative Development and The Kenyan Centre for Parliamentary Studies and Training.

The two courses taught at this year’s residency were Contemporary Issues in Parliamentary Governance – for elected members, and Current Trends in Parliamentary Administration – for staff. The residency was interspersed with speakers and distinguished guests complimenting the in-class material.

“The uniqueness of the residency lies in the issues that come out of the training,” says Rick Stapenhurst, PhD, Associate Professor, Administration & Governance domain at SCS. Stapenhurst is a former board member at Parliamentary Centre, member of Transparency International, and North American co-chair of the Research Committee of Legislative Specialists.

“We listen to the participants’ issues, needs, and concerns. We digest what we hear and generate practical research projects,” he says. “It is action learning. We learn from the students. We discuss. They [the participants] produce solutions.”

Public participation and communication

Sam Griffith and Rohan Tyler are part of the parliamentary staff in South Wales, Australia, specifically as members of Scrutiny and Engagement Legislative Assembly. They must be apolitical to provide statistics and other information to help MPs from both parties make informed decisions.

“The residency allows us to step back and reflect on what we do,” says Tyler, “To share ideas with colleagues. It is an awesome opportunity to learn.”

And what does Tyler hope to bring back to South Wales?

“To increase the public participation in law-making process, to connect people directly with committees.”

Griffith added that in South Wales, “We pass legislation too quickly. We need the public to be more involved.” He cited Kenya as an excellent example where the “public are front and center in the political process.”

This type of effective communication between the public and political process is paramount to Lacija Tacer’s (MP Slovenia) vision. She began her career as a musician and a songwriter, to “communicate with people, to make a positive change in society.” Ultimately, Tacer discovered that a formal framework like politics was a more effective tool to make a direct impact. The pandemic opened an unforeseen door.

“Following the pandemic there was a lot of dissatisfaction with the government due to democratic backsliding,” says Tacer. “They got quite comfortable not following legislative procedures and put a lot of pressure on independent media. This resulted in record voter turnout in Parliamentary elections last May as well as the creation of a new political party called The Freedom Movement. I am its youngest member. The party gives a very important role to young people.”

Tacer sees the residency as a good opportunity to “critically assess” her priorities in parliament, “to see what other people are focusing on in their countries and communities.”

Tacer’s willingness to learn, to improve her respective parliament was echoed by other attendees, a refreshing reminder that democracy is a goal, a process.

The importance of inclusion

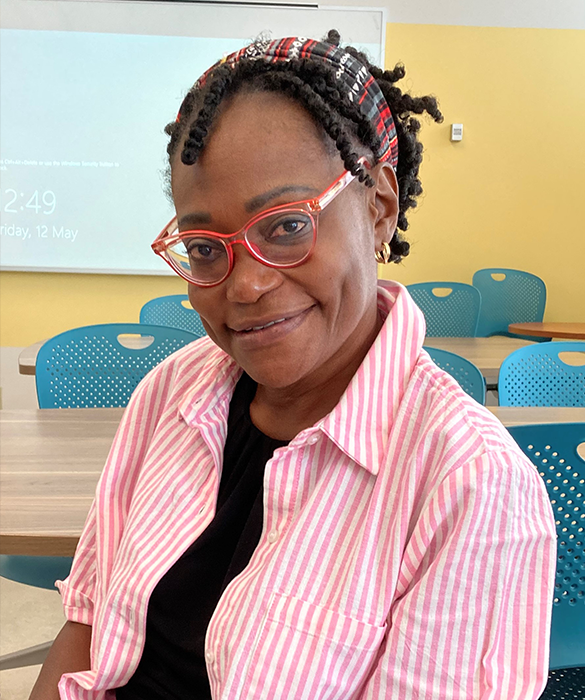

Jacqui Sampson, (Clerk, Trinidad and Tobago) appreciates working for an institution like Parliament, one responsible for the development of her society. Every year Sampson sends a group of staff to McGill. This is the first year she has attended, both as a guest lecturer and a learner.

“During the week, I have been able to question what I’ve been doing. We are performing some things well, but now I know how we can do them better,” she says. “What McGill does is expose you to various options that have been tried elsewhere and worked. You leave here with a tool kit of reforms and measures you are eager to take home and try.”

Sampson praised the residency for being a significant catalyst in improving the accountability of her government back home.

“In 2009, we had around 100 questions a year posed [by MPs to Ministers] in our elected house. In 2019, we saw 600 or more questions.”

Similarly, the number of reports prepared by the oversight committee and presented to parliament spiked from two in 2009 to 80 ten years later.

Professor Stapenhurst visited Trinidad and Tobago in 2015 and carried out an assessment of the country’s parliament and as Sampson notes, “It was not a good one. It was truthful. Our oversight was weak. There was a lack of political will to deepen democracy, to engage stakeholders, and citizens.”

Thanks to his report, four strategic objectives were broken down into different actions. Changes were made.

“This type of research on parliamentary development,” says Sampson, “is what the residency is all about, to develop an understanding that the challenges of governance yesterday are different to the challenges today, such as the importance of diversity and inclusion and the rise of populism.”

Sampson is very grateful to residency programs like McGill’s because they invigorate you and offer ideas on how to deal with all these new issues.

“If you don’t sit back every so often and reflect on inclusion, you could have a less represented democracy and the dangers that brings,” says Sampson. “Parliaments should invest in programs like the McGill SCS Residency and ensure that they send Members of Parliament and staff as often as they can. It’s very important.”