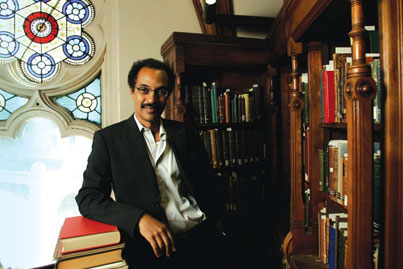

It’s been almost 20 years since a fundamentalist Islamist regime unleashed unprecedented levels of violence and terror on Sudan. Now Khalid Mustafa Medani is exploring the socio-economic conditions that gave birth to this dark period in his homeland’s history and continue to drive the worldwide politicization of Islam in the 21st century.

By Jonathan Montpetit

When an Islamic fundamentalist-backed military regime overthrew Sudan’s democratically elected government in 1989, Khalid Mustafa Medani followed the lead of the thousands of pro-democracy Sudanese activists who had previously toppled military regimes: he took to the streets in peaceful protest. But tear gas, the once-standard response to civil disobedience, soon gave way to unprecedented levels of widespread human rights abuses across the country. “In the north,” Medani recalls, “the new regime established secret prisons—where suspected dissidents were tortured, starved and denied access to legal counsel—and initiated widespread repression of civil society organizations. In the south, aerial bombardments and scorched earth policies claimed the lives of thousands of innocent civilians.”

Soon after the regime came into power, Medani left Sudan to continue his studies, earning a PhD in political science at the University of California, Berkeley. He then joined Stanford University’s Center for International Security and Cooperation, where he continued the research he had begun in Sudan. It was primarily during his time at Stanford that Medani realized the developments he had witnessed in Sudan in the late 1980s—including the pattern of militant recruitment—actually represented “a microcosm of a larger phenomenon concerning the politicization of Islam in Africa and the Middle East.” Consequently, he focused his own research on a number of countries which, in the language of political science, represent “most similar” cases: Sudan, Egypt and Somalia. Having witnessed the potential ramifications of the politicization of Islam in Sudan, Medani keenly realized that “an in-depth comparative study of the economic and social factors driving fundamentalist and militant Islamist movements is essential if Sudan and other Muslim majority countries are to transition into more democratic forms of regimes that uphold and protect the human rights of all their citizens.”

This objective led Medani into what has become one of the most topical fields of academic study: the roots of militant Islam. In 2007, he was among 21 scholars awarded prestigious Carnegie Scholarships from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, a philanthropic organization dedicated to “the advancement and diffusion of knowledge and understanding”; all of the 2007 Carnegie scholars were chosen because their work explores themes relating to Islam and the contemporary world.

“The rise of Islamic movements was important in Sudan and the Middle East and East Africa at the time,” says Medani, now an assistant professor of political science and Islamic studies at McGill, “but I had no idea how important it would become to the world after September 11, 2001. Sudan was the first Arab Sunni country to be taken over by fundamentalists, who overthrew a weak, but democratic, regime via a military coup d’état. Many people in Sudan and the Middle East, myself included, have long been aware of the danger of Islam in its militant form, but—although nobody could have predicted the events of 9/11—most analysts in the United States underestimated how these developments, far away from the West, would eventually engender global potential conflict.”

The Carnegie money—$100,000 (U.S.) over two years—will allow Medani to perform the necessarily lengthy periods of extensive ethnographic fieldwork in Sudan, Somalia and Egypt. Over the course of his almost 20 years of research in the region, Medani has built a wide-ranging network of contacts and informants—including members and leaders of Islamist movements, disenchanted ex-Islamists and government bureaucrats—that will prove crucial to his ability to safely conduct interviews and engage in participant observation. “The Islamist movement is not monolithic in Sudan,” he explains. “Contrary to popular misconceptions, jihadists remain a minority in Muslim countries, so it is possible to conduct this kind of research with a careful eye toward avoiding the dangers that are present. But to do so requires having established long-term trust.”

Medani disagrees with the essentialist, orientalist view that something inherent to Islam drives people to violence. “The notion that Islam stands in opposition to Western values and outside global norms of rationality has been exaggerated,” he says. “There’s a long tradition in the academy of this paradigm, but it’s inaccurate. For one thing, it underestimates historical change—such as the increasingly dense political and economic cooperation between Islamic and Western countries—and the simple fact that the majority of Muslims practice their religion without recourse to violence or even engagement with politics. More crucially, it obscures the very real socio-economic roots of this movement and ignores issues of social inequity and the decline in the quality of life among many Muslims. Such misinformation is leading to a great deal of conflict between the West and Muslim countries, and it is dangerously obstructing any efforts toward international cooperation and security following the tragic events of 9/11.”

Medani is therefore focusing his attention on political economy. During the 1990s he was among the first scholars to stress the link between the expansion of informal economies and informal financial flows (i.e., the black market) and the financing that buoyed the successful rise of Islamist politics. (The Sudanese black market, for one, represents upwards of 30 per cent of that country’s economy—and was essential to bankrolling the 1989 coup.)

Such an approach is not always popular. “When you talk about the socio-economic roots of terrorism,” he says, “many assume that you are, in some way, an apologist for political militancy or even terrorism.” But he is undeterred by such accusations because of his passionate belief that his work will help promote political and cultural pluralism in the Muslim world—and make at least a modest contribution to improving understanding between Western and Muslim communities. Some years ago, Medani told his parents in Sudan that he wanted to write about more optimistic political developments. He has never forgotten their answer: “One should write about what is important to others, and what provides a genuine public service.”

Next: Out of the Classroom