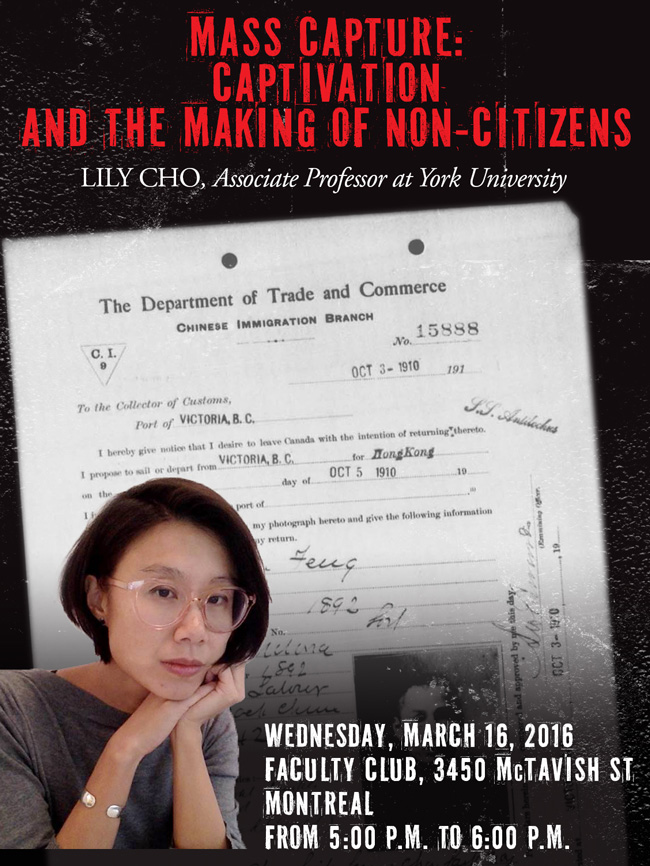

Lily Cho is an Associate Professor at York University. Her book, Eating Chinese: Culture on the Menu in Small Town Canada, examines the relationship between Chinese restaurants and Canadian culture. She is a member of the Toronto Photography Seminar. Her essays have been published in journals such as Interventions, Canadian Literature, and Photography and Culture. She is currently conducting research on two projects. Mass Capture: Chinese Head Tax and the Making of Non-Citizens in Canada examines the relationship between surveillance and citizenship. Asian Values: Fictions of Finance and Beautiful Money explores diasporic movement and theories of value in postcolonial Asia.

Lily Cho’s lecture will look at the Chinese Head Tax levied on Chinese immigrants to Canada between 1885 and 1923 as a practice of “mass capture”. Through an examination of the Chinese Head Tax, Lily Cho will explore the argument that mass capture is a technology that is central to the making of non-citizens in Canada. March 16, 5 p.m., McGill Faculty Club. Get more information about the lecture.

The focus of your research and writings has been the Chinese diaspora, particularly in Canada. Has Chinese immigration to Canada been constant throughout the last century? How come?

While the Chinese diaspora has been a significant presence in Canada, one that precedes Confederation, Chinese immigration to Canada has not been constant throughout the last century. From 1923 to 1947, Canada amended the Chinese Immigration Act to exclude the vast majority of Chinese migrants from entering Canada. That legislation is still often referred to as the “Exclusion Act.” This legislation separated families for decades and exacerbated the isolation of Chinese immigrants in Canada. Notably, this legislation was repealed only months after the inauguration of the Canadian Citizenship Act in 1947. Prior to January 1, 1947, Canadian citizens did not exist. There were British subjects who resided in Canada, but there was no such thing as Canadian citizenship.

With the beginning of Canadian citizenship, there was a national conversation about race and citizenship. In the first months of 1947, there were extensive debates in the House of Commons about the racial and ethnic identity of Canadian citizens. These conversations led directly to the repeal of the Chinese Immigration Act in May, 1947, and an end to the era of exclusion. If you read the debates in Hansard from this period, you will see that parliamentarians really struggled with the place of Chinese people in Canada in those first heady months of Canadian citizenship. I am fascinated by the very particular relationship between Chinese immigration and the emergence of citizenship in Canada.

You wrote a book, Eating Chinese: Culture on the Menu in Small Town Canada, which explores how Chinese restaurants became a sort of liaising force between Chinese immigrants and their non-Chinese neighbours. How important has Chinese food been over the decades to the integration of Chinese immigrants into Canadian society, and developing the unique Chinese-Canadian identity?

Chinese food and Chinese restaurants have been essential to the development of Chinese-Canadian identity. The restaurants have been just as important as the food. They were some of the first gathering places for non-urban communities. They were places of daily ritual and celebration. These restaurants were the site of coffee and eggs in the morning, first dates, lunch after church, and milk shakes after the hockey game. They were also the first place where someone who was not Chinese might have tasted Chinese food. This food – chicken balls, chow mien, ginger beef, fried rice – may or may not have been “authentically” Chinese. For me, its authenticity is not all that relevant. I am much more interested in the fact that this food was on the menu at all, that it was explicitly labeled “Chinese,” and that this Chinese food was juxtaposed on the menu across from food that was explicitly labeled “Canadian.” Chinese restaurants named Canadian food for Canadians. They did so through a remarkably consistent menu that varied little from town to town.

Long before fast food and the industrialization of food service, Chinese-Canadian restaurants offered food served quickly and with striking consistency despite the fact that these were all small businesses that were owned and operated by immigrants from a range of backgrounds and histories. Out of this menu, one that you will still find in any small town Chinese restaurant in Canada, Chinese identity in Canada develops in conversation with Canadian identity.

Could you explain to our readers what the Chinese Head Tax was, how it was applied, and its implications for Chinese immigrants wanting to create a new life here in Canada?

In 1885, Canada passed the Chinese Immigration Act. It was meant to limit Chinese immigration to Canada. A “head tax” of $50 was one of the key features of this legislation. Every Chinese immigrant arriving in Canada would have to pay this tax. This legislation was amended in 1887, 1892, 1900, and 1904 when the tax was raised to $500. This tax was not levied on any other group of immigrants coming to Canada. The tax severely limited economic opportunities for Chinese immigrants and kept many families apart. The era of the tax ended and was replaced with outright exclusion in 1923, thus further devastating many families who had already suffered decades of separation.

Do you see any parallels between the Chinese experience of the early 20th Century and the current migrations from war-torn countries, such as Syria?

I am more struck by the differences than the parallels between Chinese immigrants of the early-twentieth century and current migrations from countries such as Syria. The idea, the figure, of the refugee did not exist in the early-twentieth century. Certainly, people experienced violent political, social, and economic devastation in the early part of the twentieth century. And these experiences led to waves of departures, involuntary migrations, and the desire to be somewhere, anywhere, that might offer the promise of a better life. But, significantly, there were no formal refugees. Even though the suffering that creates refugees is not at all new, the refugee is actually quite new. I am moved and inspired by the work of Canadians who provide refuge, and who understand this country as a place of refuge. This work is ongoing and belongs to us all.

Get more information about the lecture.