By Billy Shields

There are over two million drivers aged 65 and up on Canada’s roads. Yet the science of evaluating motorist fitness is inexact — and that’s not good for the many safe drivers who rely on their cars to be independent. Researchers in McGill’s School of Physical and Occupational Therapy are part of a nationwide project to better decide which drivers get the green light.

Imagine living in a country where you had to get a medical exam to keep your licence to drive. After five years, you’d need another doctor’s note, and then another, and another. And what if there wasn’t consensus about whether things like blood pressure, cognitive faculties or reflexes were the best predictors for driving ability, anyway?

Would it surprise you to learn you live in that country already?

Enter Isabelle Gélinas, an associate professor in the Faculty of Medicine’s School of Physical and Occupational Therapy (SPOT). Gélinas is overseeing the Montreal site of Canadian Driving Research Initiative for Vehicular Safety in the Elderly (CanDRIVE), a groundbreaking study that promises to create new metrics to precisely gauge motorist fitness — a crucial breakthrough for seniors who depend on staying on the road to connect with the world and enjoy life in later years. CanDRIVE is a five-year, pan-Canadian multicentre longitudinal study. For the Montreal site, Gélinas is working with SPOT colleagues associate professor Nicol Korner-Bitensky and assistant professor Barbara Mazer, as well as research associates Minh-Thy Truong and Felice Mendelsohn Wise, and research assistants Rivi Levkovich and Susie Schwartz. The project is now in its second year.

According to Transport Canada, almost 2.8 million Canadians aged 65 and older hold a driver’s license. Yet the science of determining a driver’s competence remains extremely inexact. Given that in 25 years about one-fifth of Canada’s drivers will be more than 65 years old, there’s an increasing urgency to refine the evaluation process. The researchers aim to develop assessment standards that would help general practitioners keep safe drivers on the road. CanDRIVE researchers also hope to offer up customizations to the licensing process — such as day- only or no-highway driving — and minor accommodations for seniors who could retain safe driving skills by making changes in their driving style.

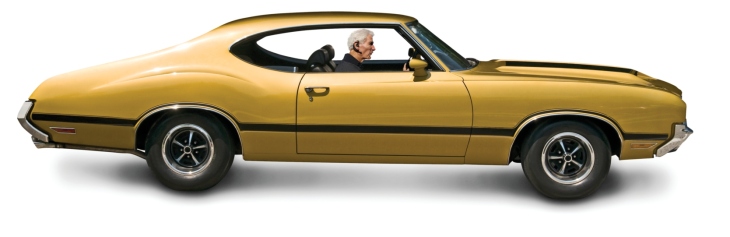

“We do change with age, but most seniors are good drivers, adjust their driving and keep up with changes,” Gélinas says. She explains that an average driver’s crash-per-kilometre ratio generally makes a U-shaped graph, with high ratios at the beginning and end of one’s driving career. While the poor performance of young drivers is often explainable by distractions and inexperience, she says, aged driving is a more complex phenomenon. Some studies demonstrate that a driver’s crash-per-kilometre ratio doubles after age 70, but Gélinas is quick to note this is often the result of accumulated conditions that are not necessarily due to the number of years on a person’s odometer: Declines in visual attention (not eyesight, but how well one pays attention to visual stimulus in the environment), longer reaction times and declining motor functions all can contribute to a driver’s performance. When seniors become unfit to drive, she explains, “it’s not because you’re old, it’s associated medical conditions” that people traditionally infer are due to old age.

The McGill researchers are working with more than 100 Montreal drivers aged 70 and older in an effort to graph driving performance across a wide swath of the senior population. (Overall, the study involves almost 1,000 participants in seven test cities: Hamilton, Montreal, Ottawa, Thunder Bay, Toronto, Victoria and Winnipeg.) CanDRIVE participants must be at least 70 years old, live in Canada for at least 10 months of the year (no snowbirds allowed), and be free of certain serious health conditions such as macular degeneration. A few times a year, researchers test the seniors on a host of data points including physical, behavioural, cognitive and clinical factors. There are two shorter follow-up appointments.

The researchers also use an in-car recording device (ICRD) to collect detailed data about the drivers’ everyday habits. With a global positioning system aerial that sits near the windscreen, the ICRD records the types of roads a driver uses, braking habits, and even whether the driver gets into an accident in a shopping centre parking lot — a potential red flag in driver fitness.

General practitioners asked to fill out forms from Canada’s provincial licensing agencies increasingly turn to occupational therapists like SPOT research associate Felice Mendelsohn Wise for advice on what to look for in driver fitness evaluations. “Seniors shouldn’t be targeted because of age. It’s not age itself that makes a driver unsafe,” she says. “There are conditions that can com- promise our strength, conditioning and reaction times. It’s very difficult to say why someone can’t continue to drive. We have people in their nineties who are enrolled in the study and are so sharp.” (A driver can go even beyond their nineties — there are seven centenarian drivers in Quebec — and still retain enough mental and motor skills necessary to drive.)

Potential drivers with mild cognitive impairments (known as MCIs), such as memory loss, are in an especially precarious position in Quebec, she said, because the services available to assess their driving fitness are scarce. “If you have an MCI there’s nowhere public for those people to get this assessment,” she says, adding that private assessments for MCI patients can cost upwards of $500.

So far governments have been encouraging. Recently the Canadian Council of Motor Transportation Admin- istrators, comprised of federal and provincial driving safety researchers, launched a task force calling for this sort of research. Getting the study off the ground hasn’t been easy, as research assistant Rivi Levkovich noted during a visit to the Kirkland CanDRIVE centre. She looked at the ICRD she planted in the steering column of a navy blue Ford Taurus SEL. It’s one of more than 100 such small boxes that have been installed in Montreal- area cars.

One of the biggest obstacles the study hit may offer an unscientific argument for keeping seniors on the road — researchers struggle to keep up with the participants. Many seniors in the study are so active and so mobile that they leave the ICRD behind when they change cars. “You have no idea how many times a senior citizen buys a new car,” Wise laughs. “And every time they do, we have to de-install the device and reinstall it into the new car.”

CanDRIVE is principally funded by a $1.1-million grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The universities participating in CanDRIVE are Lakehead University, the University of Manitoba, McGill University, McMaster University, the University of Ottawa, and the University of Victoria. The University of Michigan and Monash University (Australia) are also partners.