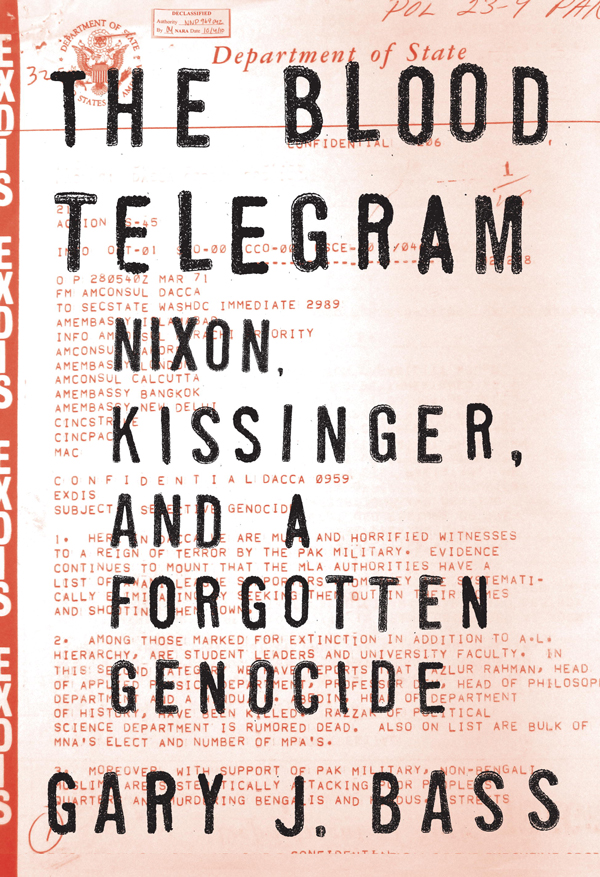

Gary Bass is a professor of politics and international affairs at Princeton University. A finalist for the Cundill Prize for Historical Literature for his book, The Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide. A former reporter for The Economist, he has written often for The New York Times, as well as writing for The New Yorker, The Washington Post, The Los Angeles Times, The New Republic, Foreign Affairs, Foreign Policy and other publications. The Cundill Prize, now in its seventh year, features a $75, 000 U.S. grand prize, the most lucrative international award for a nonfiction book. The winning title will be announced on Nov. 20. Bass took some time to answer Four Burning Questions from the Reporter in advance of the Nov. 20 ceremony.

Please describe what level of dedication it takes to produce such a comprehensive piece of historical literature? What type of regime do you follow?

There are really two tasks, the research and the writing, which together took years. This was an investigation which required digging around in American and Indian archives, lots of interviews with participants in America and India and Bangladesh, and strangest of all, the White House tapes, which capture what Nixon and Kissinger were actually saying when nobody else was around.

The White House tapes are terrible to work with – they’re huge, they’re organized in a frustrating way, there are lots of bleeps of material on ostensible grounds of national security, the sound quality is sometimes bad, the conversations are meandering and messy. There’s an excellent book of fresh transcripts from the tapes made by Douglas Brinkley and Luke Nichter, which just came out, which demonstrates how hard this material is to work with. You have to listen to each sentence over and over again. If I wasn’t totally sure that I had the quote right, I wouldn’t use it. But what you get out of the tapes, in the end, is really worth it. There was no bureaucratic or diplomatic filter, just their raw voices, at the highest level. You hear directly Nixon’s bigotry against Indians, his fondness for the Pakistani military dictator, Kissinger’s remarkably emotional reactions.

I got thousands and thousands of pages of documents from U.S. and Indian archives. The American documentary record is colossal, and the State Department has done impressive work in declassifying papers. India is still much more opaque about its own national security documents than the United States is, but the archivists at the National Archives and the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, both in Delhi, have done remarkable work. You can find amazing things in these Delhi papers, like secret Indian records of how they were sponsoring a Bengali guerrilla insurgency inside East Pakistan.

The interviews were fascinating to do, and were very rich. These people lived it. Because you’re talking about memories from four decades ago, and hindsight can be self-serving, I based the interviews on documentary evidence, and checked their recollections closely against the paper trail before anything went into the book. I tried very hard to talk to Henry Kissinger, to include whatever he wanted to say. I did manage to talk to his White House staffers working these issues, to get the White House perspective, but Kissinger first ignored my requests and then refused.

I had a wise editor once who told me to write for a standard eight hours every day, whether you feel like it or not. Long books are hard because of both structure and line. The writing was structurally complicated because there the narrative jumps back and forth between Washington, Delhi, and Dhaka, and you need to get the interplay of their different perspectives, but you don’t want to retell the same events. There was so much inherent drama and suspense in what happened, and the challenge was to capture that on the page.

What led you to uncover this previously unknown and shocking chapter in American history?

I was doing research for an earlier book in Bosnia after the war there, and randomly brought along a book and read something about this slaughter in Bangladesh, which embarrassingly I knew nothing about. That stuck in my mind, and much later I had the time to do some digging to remedy my ignorance. Kissinger’s version of what happened in his memoirs was obviously incomplete, so I did some more digging, and realized that this was going to require much more sustained work in archives and the Nixon tapes. As it unfolded, it was stunning how much more there was to the real story.

What do you hope readers of The Blood Telegram will come away with when they read it?

For a start, it would be good for people simply to remember this important chapter of the Cold War. Everyone remembers Vietnam or the Yom Kippur War, but not this. It’s notorious and traumatic in South Asia, but forgotten over here. There are massive consequences to this day for a strategic and heavily populated part of the world. Beyond that, every reader will judge Nixon’s and Kissinger’s actions in their own way, and it’s not up to me to dictate what they should take away from it, but at least they should be aware of the core facts, and then we can have that debate properly. Things were always going to be hard in Bangladesh no matter what. It’s hard for countries that have gone through this kind of mass atrocity when their suffering isn’t even remembered, when they feel like they have to struggle just to have their history recognized at all. And hopefully the book can help readers reflect on these enduring dilemmas in foreign policy between realpolitik and conscience, which are salient long after Nixon is gone.

How important is the Cundill Prize and literary awards in general? What kind of effect would winning one have on your work?

They’re always a nice surprise. It’s wonderful and humbling to be on any list with folks like Richard Overy, David Van Reybrouck, and David Brion Davis, and others. Anyone on that shortlist has done years and years of work and it’s good to see the recognition. Writing a long book means a lot of isolation and self-criticism, and you never know if the book will turn out all right, so any sense that the thing has actually reached real people is a relief.

It’s increasingly difficult for serious nonfiction to find its audience. There are lots of books being published, but less and less space for book reviews, and fewer and fewer physical bookstores where readers can browse or benefit from the good taste of a good indie bookseller. Awards are a pleasant way of keeping books from getting lost in the shuffle.

To learn more about the Cundill prize, go here.

To read a Q&A with David Van Reybrouck, another Cundill Prize finalist, go here.

To read a Q&A with Richard Overy, another Cundill Prize finalist, go here.