Interview with the Right Honourable Joe Clark

By James Martin

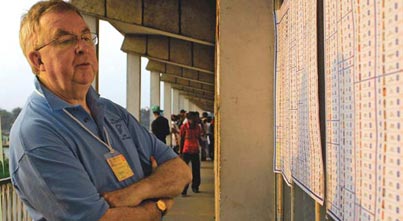

Joe Clark’s deep relationship with the people of Africa began when, as Prime Minister of Canada, he visited Cameroon while en route to the 1979 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Zambia. In 1984, as Canada’s Secretary of State for External Affairs, he was the first politician from a developed nation on the ground during the Ethiopian famine. His unwavering support of economic sanctions distinguished Canada in the battle against apartheid. Now Professor of Practice for Public-Private Sector Partnerships at the McGill Centre for Developing-Area Studies (CDAS), Clark continues his dedication to Africa’s development challenges.

You’ve recently observed elections in Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Nigeria. From the CDAS perspective, does governance take precedence over poverty?

It’s not a choice; you have to pursue both paths simultaneously. When the DRC election results were coming in, the CBC asked me—to my surprise—”Look at all the money the UN is spending on this election. Why aren’t you curing poverty?” Well, you can’t cure poverty in the midst of conflict. The only long-term response to conflict is to have institutions that can be accepted in the community and add some stability.

Now, obviously, if those institutions are only used to enrich the powerful, that’s counterproductive. But what, in fact, is quite consistently happening is that when those institutions work, poverty alleviation becomes a policy priority. If you leave the violence and try only to deal with the evidence of the poverty, that poverty will persist. If all you do is create an electoral system, and don’t have a society deal with its real issues, then that electoral system is not much use. The two must go together. And there’s an obligation to be sure that the things we’re doing in the name of governance work.

What steps can be taken to better ensure that success?

It’s very important to incorporate indigenous models. One of the people CDAS works with is Howard Wolpe, who heads the Africa Program of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. His thesis is that Western models are too much based on conflict among interests, whereas the society in Africa is much more cooperative. That’s among the issues we want to look at during a conference we’re holding in mid-March.

While I was in the DRC, I worked with Apollinaire Malu Malu, the extraordinary priest and civil society activist who became the chair of the electoral commission of DRC. He’s coming to McGill as a visiting fellow during the Fall 2008 semester; he’ll be networking with various organizations—including the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) and Elections Quebec—and NGOs, giving public and classroom lectures and, very importantly, recording his experience in running the DRC election.

Why is it so important for Malu Malu to tell his story?

The Congo elections were one of the most trouble-free elections that I’ve ever seen. It’s been 40 years since they’ve had an election, they’ve just come through an internal conflict that took more lives than any conflict since the Second World War, and yet they brought themselves together. There were killings—not as many as one feared, but any killing is too many, obviously—but the system worked very well. This was because it was designed by a transition government that had no incumbent, so the electoral law was written for the simple purpose of conducting a fair election—and the transition government was carefully constructed from the actual militia leaders and political leaders of the groups that had been killing one another. The success was also because of Malu Malu’s extraordinary skills. His record of how he did it will be important historically, and also in terms of governance now that DRC has had elections but is a long way from being a whole state. And it will be a very useful model for other developing countries.

In 1960, then British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan talked about the winds of change blowing through Africa. He might have foreseen a higher velocity of wind, but there has been extraordinary positive change—including the kinds of breathtaking political decisions we’ve seen in the DRC.

The McGill Centre for Developing-Area Studies receives funding from McGill University and CIDA.

Next: Turning Point 1963