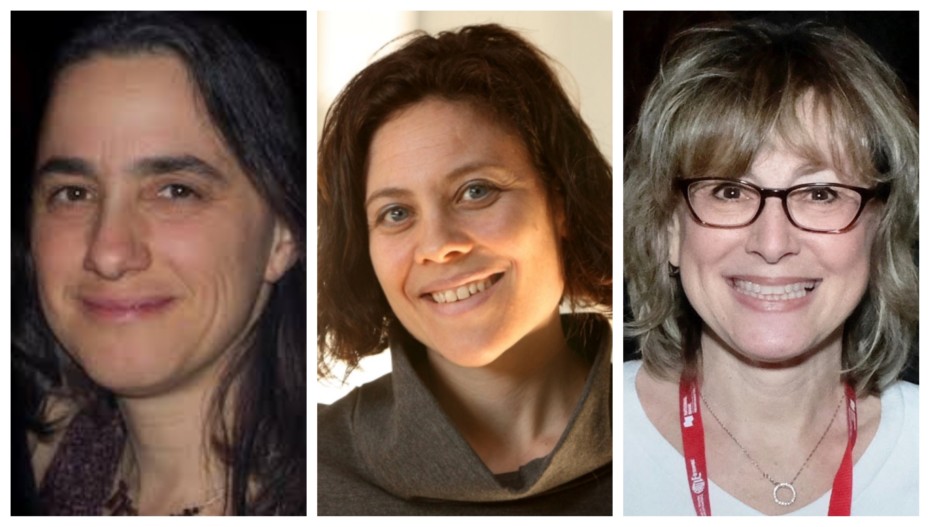

In light of the shocking reports on long-term care facilities in Quebec and Ontario, the Reporter consulted three McGill experts from the School of Social Work – PhD Candidate Susan Mintzberg and Associate professors Tamara Sussman and Shari Brotman.

In this Q&A, our trio of experts look at a broad gamut of issues related to senior care in Quebec, including the current state of affairs and what can be done to improve the situation.

How is the pandemic impacting the physical and psychological health of seniors – especially those in long-term care?

Seniors’ health is at the heart of this pandemic. Canadians have been devastated by the daily news about the ongoing crisis in long-term care. Only 4 per cent of seniors, however, reside in long-term care facilities, while most older citizens must fend for themselves, outside of the media spotlight.

Whether living in long-term care homes, retirement homes or their own homes, COVID-19 is taking a toll on seniors in multiple ways. In many instances, professional services have been cut or reduced, support from family, friends and home care workers is not possible, and seniors’ general well-being, both physical and psychological, is at risk.

It is worth noting that there has been little discussion about seniors who themselves are caregivers, volunteers or front-line workers. Some seniors are even coming out of retirement to provide assistance. In addition, many seniors have been caring for a spouse or relative for years while others have unexpectedly needed to become caregivers to family members as a result of COVID-19, often with little to no outside support.

Perhaps the most important consequence of this pandemic related to seniors, is that it has exposed concerns about how we care for our older citizens, an issue that has been ignored for far too long.

How important is it that family caregivers are now allowed in Quebec senior homes? What roles/gaps do they fill in the healthcare system?

It is critically important that family caregivers have been allowed back in. When they were removed from seniors’ long-term care homes at the start of this pandemic, the assumption was that they were visitors who needed to be kept out in order to limit the risks. But they are so much more. Family caregivers are the invisible frontline workers in our healthcare system. As we saw right at the beginning of this pandemic, when we pulled the plug on families, the ship began to sink.

Our government must now face the fact that families have an essential role. They often provide the personalized care that our system is not equipped to offer. This includes linguistic, cultural and mental health support. Families know the everyday needs of a relative, which can make the difference between accepting and benefitting from help, or not. Unfortunately, many family caregivers across the country continue to face hurdles that keep them from providing this essential care to their loved ones in seniors’ homes.

What about family caregivers who themselves are seniors? Are they being allowed to take care of their spouses? Are there added precautions to protect them?

Senior caregivers are not only allowed to take care of spouses and other relatives, but many have no choice but to provide support in the community as home care services are now limited or cancelled due to COVID-19.

Exacerbating the challenge, family caregivers in the community are not recognized as essential workers and thus, to date, have not been given any personal protective equipment. They must try and locate limited protection, such as masks, on their own or go without. This increases the risks, especially if the spouse or family member they are caring for falls ill with or shows symptoms of COVID-19.

Adding insult to injury, despite ramped-up testing by the government, many family caregivers still do not qualify or have access to tests, putting both themselves and those with whom they have contact at greater risk of becoming ill.

We all read some tragic accounts of seniors languishing in long-term care facilities because family caregivers were denied access to them in the first two months of the pandemic. What kind of impact does a prolonged period of stress and anxiety have on seniors and their families?

The media has kept us well informed about the devastating impact this has had on so many Canadians. We regularly hear accounts of seniors rapidly deteriorating within weeks, or even days, after being cut off from their families. Many have died, testing negative for COVID-19.

This is a stressful period for everyone. Seeking comfort in loved ones who can provide a feeling of safety and reassurance is essential. Having separated countless vulnerable seniors from their families, often with little or no opportunity for communication, has caused immeasurable, and often irreversible, damage to all.

Mental health and physical health go hand in hand. It is not surprising, therefore, that seniors who find themselves alone, possibly confused, maybe feeling abandoned, and certainly afraid, will experience stress, anxiety and depression. As their mental health deteriorates, so too will their physical health. Many seniors are dying of a broken heart, while their families, unable to reach and comfort them, are left with the long-term wounds of knowing they could not be there when it most mattered.

With Canadians impacted in numerous ways by the COVID-19 pandemic, it is imperative that our governments and healthcare system prepare for the mental health pandemic that is sure to follow.

What has the COVID-19 pandemic exposed about long-term care homes in Quebec and how our seniors are treated? Is this a situation that has arisen because of the pandemic, or does it go farther back than that?

The Canadian Armed Forces released a scathing review of the conditions that soldiers witnessed when they were deployed to assist in long-term care homes in Quebec and Ontario. Ontario Premier Doug Ford responded with surprise and suggested he had inherited this situation from the previous government while Quebec Premier François Legault indicated that these problems are known and longstanding and that they result from a shortage of workers. Both reactions are concerning as it should not have taken a pandemic nor a military report for our provincial governments to acknowledge and take action regarding the conditions in long-term care homes.

This is especially disturbing given that frontline workers have been shining the light on this situation for decades. Senior care is underfunded and lacks the needed support… out of sight, out of mind. Underpaid staff, insufficient workers, inadequate training, unacceptable living conditions, insubstantial communal space, unpleasant food, impossible circumstances, and the list goes on. Those working on the ground have tried to expose this reality, but those working at the top have chosen not to listen. We are now paying a very high price for top-down management that failed to pay attention to what has been so obvious for so long.

Furthermore, this problem goes beyond long-term care. Services to seniors across the continuum of health and social care, including home care, transportation, and community programming have been neglected and underfunded for decades. As a result, services have become increasingly inaccessible and inequitable, particularly with respect to marginalized older people such as those from immigrant and Indigenous communities.

What kind of changes must be made to correct the situation in the long term? Are we talking about a complete overhaul of the system?

Despite the shortcomings, there is no need to reinvent the wheel. Many reliable, compassionate, dedicated individuals devote their careers to caring for seniors. As social workers whose research focuses on speaking and connecting with those who live and work in these realities, we are keenly aware of how much valuable insight is available.

If we paid more attention and listened to the voices of our front-line workers, family caregivers and, most importantly, seniors themselves, we could ground change in the perspectives of affected people and communities, allowing for the development of new policy and programs that better address a wide diversity of seniors’ realities.

The first change that needs to occur is increased recognition and compensation for those who spend each day caring for seniors. This includes PABs, dietary and recreational aids, cleaning staff, family caregivers, etc., who work so hard and provide 80 per cent of the care, yet who have often been made invisible. Next we need to acknowledge that family caregivers are not simply visitors, but essential workers who help to sustain senior care. They need to be recognized, supported, and valued, not just psychosocially, but in ways that encourage and strengthen them.

We need to invite all of these people to the table when decisions are being taken and policies are made. If we don’t listen to those on the ground, how can we properly understand what needs to be done in order to improve the situation? Perhaps most importantly, is that as a society we must remember this crisis so that we hold our governments accountable to make changes, even long after the pandemic is over.

In some cultures, seniors are held in high esteem and taken care of as they grow older – often living with their children. Is it fair to say that for many in North America this is not the case? Why is that?

It is widely believed that ethnocultural minority communities are more likely to refuse formal services and to care for family members at home. Yet, this is a stereotype that results from a lack of understanding about the factors which contribute to the choices made by these communities. This, in turn, leads to inadequately adapted services. For example, it is common for service providers to assume that ethnocultural minority family members prefer to provide care, overlooking the wider social issues that place families in that position.

Many decisions made by ethnocultural minority families regarding care have more to do with mistrust and discrimination experienced in society and in healthcare settings than with their own cultural values. There are no shortage of examples including: a lack of language and cultural interpreters in seniors’ facilities; over-reliance on family members to give information rather than communicating directly with the older person; insufficient food choices; failure to recognize diverse religious beliefs; inattention to cultural safety for Indigenous Elders; and a total absence of networking with ethnocultural minority, LGBTQ, immigrant and Indigenous organizations who can offer recommendations about equity, diversity, and inclusiveness.

All cultural groups want to properly care for their seniors and need to know that they can rely on the appropriate support to ensure their well-being. As a society we have an obligation to provide equitable care for all.

This is an extremely stressful time for many seniors. As caregivers, what kind of emotional support can we give them?

When it comes to support during the pandemic, we are all in this together. Fear, anxiety and solitude are impacting everyone. We all seek reassurance, and for seniors who are often most isolated, this is especially important. Many people, including seniors, are using technology to reach out to family and friends in new ways that allow them to stay in touch. For those who do not have the possibility of accessing devices, alternative forms of connecting such as porch visits, sending notes and phone calls allow for continued support.

We have heard many heartwarming stories about family caregivers who have found creative ways to overcome communication barriers. Sometimes the smallest gesture can make a world of difference. Letting seniors know you are thinking of them and that they are not alone, may not seem like much, but can have significant impact on their mental health and overall well-being.

In the context of COVID-19, how important is it that we have conversations about death and end-of-life care with our seniors?

Conversations about death and end-of-life care are difficult to have, even at the best of times. Unfortunately, there is still much taboo around this subject and many families, seniors, and even health providers avoid such discussions. Yet, these are important conversations to be having in order to offer care that aligns with a person’s wishes and beliefs.

This is especially relevant in the context of COVID-19 when family caregivers may not be present at the end of life, and medical decisions about ventilators, and other heroic measures might need to be made quickly. As well, with nurses and other staff now helping families to be virtually present, having information about what comforts a person, such as playing special music or having their feet rubbed, can help to provide support to seniors and family at the end of life.

Although bringing up these issues can be challenging, it offers relief for families knowing they can make informed choices and comforting suggestions when the time comes. Tools are available to help families initiate these conversations such as the Speak Up Campaign and The Conversation Project.

Families are left to cope with grief in strange ways nowadays with restrictions imposed on funeral homes and burial sites. In the long run, how does that impact family relations?

It is not so much about the impact on family relations as it is about how social distancing and restrictions on gatherings will affect the grieving process for families who have lost a relative during the pandemic. Rituals around death exist in every culture and provide much needed comfort and support. Without direct contact to family and friends, this difficult time becomes all the more challenging. People have found new ways of coming together, such as having Zoom Shivas in Jewish communities, but nothing can replace the compassion we receive from direct human contact. Sadly, under the current circumstances, many families must grieve individually while waiting to be able to reunite at some point in the future.

Making this even more difficult is the reality that for numerous families, they must live with the fact that they could not be present at the final stages of life. Having been absent during this significant time complicates grief in ways that will have long term consequences. Families are now reliant on front line workers to provide comfort to their relatives during those last days of life and relay information or details about the final moments that might help them mourn their loss.

Finally, as testing becomes more available, it is crucial that the government and healthcare system ensure that those who show no symptoms but have been in contact with or cared for someone with COVID-19 can easily access testing. This would allow grieving families to know whether or not it is safe to come together and provide much needed comfort during this emotional time.

Susan Mintzberg is a PhD Candidate in the McGill School of Social Work. Her research explores the role of family caregivers in mental healthcare with a focus on collaboration between family members and service providers. This work evolved from ten years of practice with individuals and families in community mental health.

Tamara Sussman an is Associate Professor at the McGill School of Social Work. Drawing on over ten years of experience working with adults and families managing health related issues in both hospital and community settings, Sussman’s program of research focuses on how health services and systems impact older adults and their family members.

Shari Brotman is an Associate Professor at the McGill School of Social Work. Brotman has worked extensively, as an educator, researcher and practitioner in the fields of gerontology and anti-oppression social work practice. Her scholarly activities centre on questions of access and equity in the design and delivery of health and social care services to older adults from marginalized communities (LGBTQ and immigrant), and their caregivers.