By Patrick McDonagh

In health care, information is crucial: The data shared by doctors and nurses determine a patient’s diagnosis and care. McGill researchers with the hSITE Strategic Research Network are using new technologies to improve the speed, accuracy and efficiency of medical services.

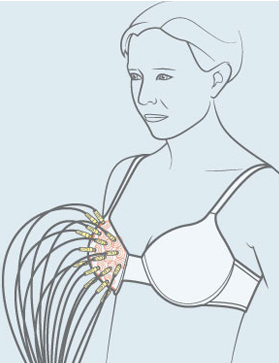

Physicians at the Cedars Breast Clinic of the McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) had an unusual order: they wanted to be able to detect the small lumps that might be signs of breast cancer without resorting to uncomfortable, and radioactive, mammograms. A team led by McGill professors Milica Popovich and Mark Coates, from the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE), in collaboration with Université Laval professor Leslie Rusch and the MUHC clinicians, delivered the “tomo-bra,” prototypes of which are currently being tested on volunteers. Worn like a bra, the device uses an array of microwave antennae to send and receive low-energy signals that produce a scan – a tomograph – of the breast tissue, enabling clinicians to spot changes in tissue density that could indicate a tumour. “The mammogram is uncomfortable, to say the least; it hurts. But the tomo-bra involves no discomfort or pain,” says Popovich, who has experienced both. While the tomo-bra would not replace mammography, it does create more diagnosis options. As Coates says, ”Because there is no need to worry about ionizing radiation, women who have a high risk for breast cancer could use the tomo-bra monthly as an early-warning system telling them if they should follow up with a mammogram.” Frequent exposure to ionizing radiation can lead to cancer.

The tomo-bra evolved within the Healthcare Support through Information Technology Enhancements Strategic Research Network. Based at McGill, hSITE has been funded since October 2008 by a $4.8 million grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), along with almost $3 million of cash and in-kind support from partners in industry and health care. The network was set up to help develop the information and communications technology (ICT) components needed to enhance efficiency in health care clinical environments. To do this, hSITE researchers consulted with clinicians to understand their needs and develop the tools to address them. “The best way to make our research useful is to work with people who have problems that need solving,” says David Plant, hSITE’s scientific director. “When we launched hSITE, it was avant-garde to connect health-care practitioners to ICT researchers developing wireless applications.” Today, many products of hSITE research are being used in partner hospitals, with some being prepared for further commercialization.

In addition to Plant, Coates and Popovich, McGill is represented in the network by ECE professors Tho Le-Ngoc and Fabrice Labeau. The network includes another 18 researchers in eight other Canadian universities, along with partners in industry – including IBM, Telus Health, which develops information technologies for health care applications, and ParaMed Home Health Care, an industry leader in home and workplace health-care services – as well as health-care providers, including the MUHC, Toronto’s University Health Network and Mount Sinai Hospital, Calgary’s Ward of the 21st Century, and Ottawa’s Élisabeth Bruyère Hospital.

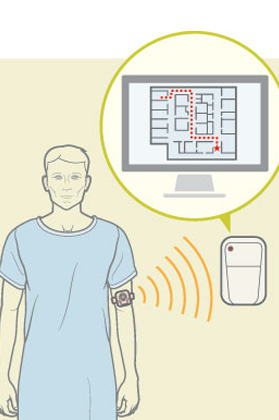

One of the technologies far beyond the prototype demo phase is a patient-tracking system developed by Tho Le-Ngoc and his team. The research team consulted closely with medical staff at the Royal Victoria Hospital (RVH)’s Division of Geriatrics Medicine to build a tracking system for patients who may wander from the acute care ward. The patients carry a small tracking device that can be worn as a watch, pinned on as a badge, or simply placed in a pocket. Consequently, staff can locate them if they roam – and the device can also trigger locks on certain doors as patients approach them. The same technology can track wheelchairs and other equipment, enabling staff to retrieve equipment when needed. It has also been used in the RVH Emergency Room to examine workflows, helping clinicians to devise the most efficient layout of ER equipment to speed up the delivery of health care.

Le-Ngoc’s team has also worked with RVH Emergency Room physicians to create a wireless connection for the vital signs monitor. “Right now the nurse reads the monitor’s output and records it on paper before uploading it into the system,” Le-Ngoc explains. “So two problems can occur: first, the data may not be correctly transcribed, and second, hours may pass between recording the information and putting it into the system.” The team has upgraded the monitors by designing attachable hardware that enables nurses to connect to the monitor via their smartphones and then upload the patient’s vital information directly to the network. “Not only is this fast and efficient,” says Le-Ngoc, “but it could be very useful when monitors are used at a distant emergency site. For example, if paramedics need to send patient information – such as blood pressure, pulse, blood oxygen levels and so forth – from a car accident site to a hospital, so the staff there can prepare to receive the patient.”

All these bits and bytes travelling over wireless networks pose a new challenge: How to manage these data? “Acquiring all the signals from all the patients in a hospital and transmitting them to a central server imposes an immense load on the hospital’s wireless network,” says Fabrice Labeau. “But not all this information is relevant or time-critical.” The system must somehow understand the particular relevance of each one and prioritize it appropriately: Emergency signals must take priority over routine monitoring signals. “For instance, electroencephalography (EEG) monitoring creates a lot of data,” says Labeau. “There could be anywhere from a few to a few dozen electrodes attached to a patient’s skull, all emitting signals.” If a patient experiences a seizure, the signal changes and clinical staff are alerted. One of Labeau’s PhD students, Hoda Daou, developed a programming technique that allows for the simultaneous compression of the EEG signals and monitoring of their regularity, thereby allowing emergency signals to still take priority.

Much of the research performed under the hSITE banner has tremendous commercial potential, making it attractive to the network’s industry partners. IBM donated its costly WebSphere software to Le-Ngoc’s team to use as a reference for the development of the patient tracking system. According to Don Aldridge, a research executive at IBM, Le-Ngoc’s project provided the company with “a real-world test environment for our then-nascent tracking technologies.… This project now serves as a key reference for IBM as we deploy similar solutions in hospital settings globally.” Other industry partners proposed avenues for research. Telus Health, for instance, worked closely with University of Toronto researcher Joe Cafazzo to investigate communications issues related to the transfer of patients between clinicians, and the technologies developed from this research may lead to commercial health care apps.

While the hSITE network will close shop at the end of 2015, the connections it has made will endure, and research will continue. The RVH Geriatrics team is considering implementing Le-Ngoc’s tracking system after it moves to its new facilities in 2015, and Coates and Popovich plan to continue testing and refining the tomo-bra at the MUHC until a prototype is ready for commercialization. In addition, Le-Ngoc and Labeau have developed international collaborations in China, building on their hSITE work to find ways to help Chinese researchers devise techniques for managing huge data loads from home-care monitoring – a growing issue in that country.

“One of hSITE’s most riveting outcomes is that we’ve gained the trust of health-care practitioners and can work closely with them,” concludes Plant. “It isn’t easy to take engineering innovations past the lab’s testing and measurement equipment and into real health-care centres with real patients.” Much of the challenge lies in forging the first links. “I know from experience that trying to establish a collaborative relationship cold, by yourself, is uphill work,” says Coates. “Just finding the right person to talk with, the person who might be interested in doing something with you, is difficult. But being part of this network is a tremendous asset. hSITE has brought together people from different communities and established a lot of communication.”

Other hSITE partners include Alberta Health Services, BlackBerry, QNX, Avaya, Carleton University, the University of Alberta, the University of Calgary, the University of Ottawa, the University of Victoria, the University of Waterloo and the Ottawa Hospital.