We hear increasingly about the difficulties of veterans trying to return to ordinary life after a stint in the military. Associate professor of social work Myriam Denov is involved with a group of former soldiers whose re-entry into society is nothing short of miraculous.

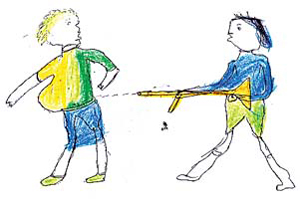

Denov works with children in Sierra Leone who have been both perpetrators and victims of violence in armed conflict. Many were abducted, forced into armed groups and ordered to murder, rape and torture “enemies,” mainly civilians. The young people— girls as well as boys—were often fed powerful drugs to gear them for combat.

Since the decade-long civil war ended, these youth have had “enormous issues of guilt and shame to deal with,” says Denov. “Many communities rejected the children. They couldn’t go home so they migrated to urban areas where they could remain hidden.”

For some, life is still harsh. Denov, whose book Child Soldiers: Sierra Leone’s Revolutionary United Front will be released in January 2010, has met many former child soldiers. “I came across a slum community in Freetown where I found the worst of the worst-off living on the streets; no family, no support system, no school. They’ve remained in semi-militarized structures because it’s all they know. It’s incredibly grim.”

But not all stories are bleak. “Girls are doing a good job bringing up children born of rape. And there are cases of young people who have carved out a new niche.” She cites a group who worked cooperatively to set up a motorbike taxi business, even organizing unions. “They are learning to use political means and to get what they need in non-violent ways. It does give you hope.”

Professor Denovʼs research is funded by SSHRC.