by Jennifer Towell

Interview with Shree Mulay

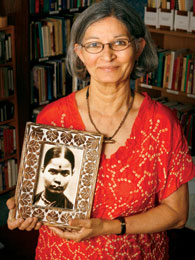

Owen EganShree Mulay, Director of the McGill Centre for Research and Teaching on Women since 1996, is a professor in the Faculty of Medicine whose main research interest is women's reproductive health. A founding member and past president of the South Asian Women's Community Centre in Montreal, Professor Mulay has maintained a lifelong concern for poor, uneducated and immigrant women. She has also been a mentor to other women working in science. Her work has been recognized by numerous awards, and she is a frequent media commentator on women's issues.

How did you become interested in women’s issues?

Growing up in India, I was acutely aware of the downtrodden position of women. My grandmother was widowed at 28 and left to fend for herself and her three daughters when distant relatives bilked her out of a home. She may have been illiterate, but she was highly intelligent and determined that her children would receive an education. Her daughters and granddaughters were expected to study hard—which we all did! However, education was no guarantee we would not face discrimination as women at personal and political levels.

Two other women have had a very important influence on me. Madeleine Parent, a trade union organizer and a feminist from Quebec, invited me to become involved with the National Action Committee for the Status of Women, which opened my eyes to what concerned women from across Canada.

Ursula Franklin showed me that no matter what you do as a scientist, you have to be true to your own values. She has been an ardent advocate for peace, and I take inspiration from her engagement with so many issues.

As a medical researcher, you take into account the female perspective. Describe your motivation and your work.

For a long time, females were considered to be unsuitable as research subjects by male scientists because their “messy” cycles had to be taken into account.

What has shaped my research questions most is whether what I was doing had any impact on women’s health. For the past few years, I have reoriented my research to reflect socially relevant issues, namely women’s experiences with sterilization, sex-selective abortions and new reproductive technologies.

The contrast between the experiences of women from developed and developing countries is huge. I am concerned about clinical trials on contraceptives in countries such as India, and the pressing need to develop ethical guidelines for these trials.

What other major issues are you researching?

I work with colleagues in India to study the impact of liberalization of trade regimes on access to health services and medicines. I also work on a long-term follow-up of children exposed to methyl isocyanate in their mothers’ wombs when gas leaked from the Union Carbide factory in Bhopal, India, in 1984—the world’s largest industrial disaster. We work with the Sambhavna Clinic, which provides free medical care for victims of the Bhopal tragedy.

You advocate strongly for women in science. Why is this important?

Ursula Franklin has a great line about this; she asks us to imagine working with only half a brain! Any society that relies exclusively on those who carry the XY chromosome is missing a great deal. Women have to participate in science not just for their own good, but also to ask questions which have been unformulated because of gender biases.

We have come a long way since the exclusion of women from the scientific endeavour. There is greater acceptance of women as scientists; slowly but surely, the barriers are coming down.