A historic collaboration of scientists around the world, with contributions by a McGill physicist, has lifted the veil on a cosmic mystery by proving the existence of black holes.

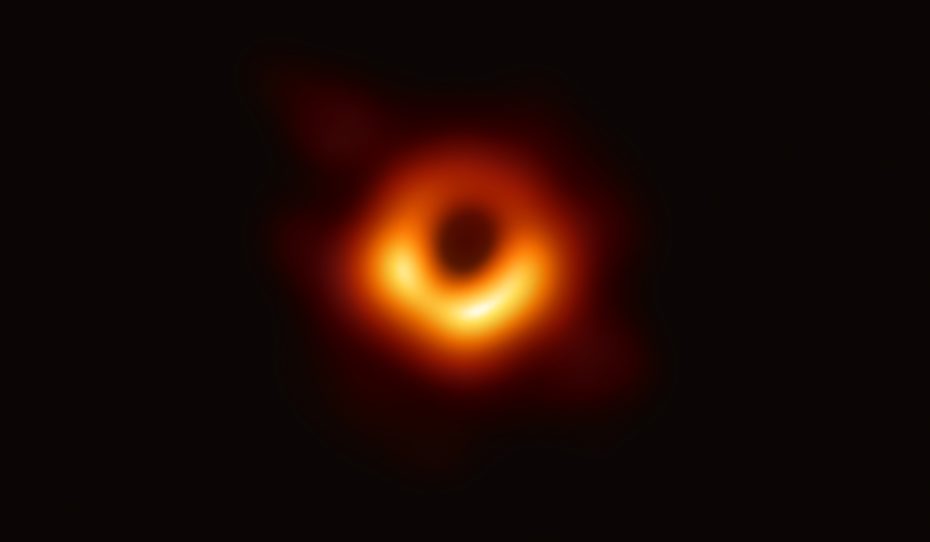

The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) — a planet-scale array of eight ground-based radio telescopes forged through international collaboration — was designed to capture images of a black hole. Today, in coordinated press conferences across the globe, EHT researchers reveal that they have succeeded, unveiling the first direct visual evidence of a supermassive black hole and its shadow.

This breakthrough was announced today in a series of six papers published in a special issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters. The image reveals the black hole at the centre of Messier 87, a massive galaxy in the nearby Virgo galaxy cluster. This black hole resides 55 million light-years from Earth and has a mass 6.5-billion times that of the Sun.

Professor Daryl Haggard of the Department of Physics and the McGill Space Institute in Montreal contributed to two of the publications released today, as a member of the EHT’s Multi-wavelength Science Working Group. “The warping of spacetime around the massive black hole in M87 is so extreme that light captured by the EHT is showing us the space in front of and behind the black hole at the same time,” Haggard said. “Theorists predicted what this would look like – a concept simulated, for example, in the movie Interstellar – but we’re seeing it in real life for the very first time.”

Einstein’s prediction

The EHT links telescopes around the globe to form an Earth-sized virtual telescope with unprecedented sensitivity and resolution. The EHT is the result of years of international collaboration, and offers scientists a new way to study the most extreme objects in the Universe predicted by Einstein’s general relativity during the centennial year of the historic experiment that first confirmed the theory.

“We have taken the first picture of a black hole,” said EHT project director Sheperd S. Doeleman of the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian. “This is an extraordinary scientific feat accomplished by a team of more than 200 researchers.”

Black holes are extraordinary cosmic objects with enormous masses but extremely compact sizes. The presence of these objects affects their environment in extreme ways, warping spacetime and super-heating any surrounding material.

“If immersed in a bright region, like a disc of glowing gas, we expect a black hole to create a dark region similar to a shadow — something predicted by Einstein’s general relativity that we’ve never seen before,” explained chair of the EHT Science Council Heino Falcke of Radboud University, the Netherlands. “This shadow, caused by the gravitational bending and capture of light by the event horizon, reveals a lot about the nature of these fascinating objects and allowed us to measure the enormous mass of M87’s black hole.”

Multiple calibration and imaging methods have revealed a ring-like structure with a dark central region — the black hole’s shadow — that persisted over multiple independent EHT observations.

“Once we were sure we had imaged the shadow, we could compare our observations to extensive computer models that include the physics of warped space, superheated matter and strong magnetic fields. Many of the features of the observed image match our theoretical understanding surprisingly well,” said Paul T.P. Ho, EHT Board member and Director of the East Asian Observatory. “This makes us confident about the interpretation of our observations, including our estimation of the black hole’s mass.”

Global network of telescopes

Creating the EHT was a formidable challenge which required upgrading and connecting a worldwide network of eight pre-existing telescopes deployed at a variety of challenging high-altitude sites. These locations included volcanoes in Hawai`i and Mexico, mountains in Arizona and the Spanish Sierra Nevada, the Chilean Atacama Desert, and Antarctica.

The EHT observations use a technique called very-long-baseline interferometry (VLBI) which synchronises telescope facilities around the world and exploits the rotation of our planet to form one huge, Earth-size telescope observing at a wavelength of 1.3mm. VLBI allows the EHT to achieve an angular resolution of 20 micro-arcseconds — enough to read a newspaper in New York from a sidewalk café in Paris.

The telescopes contributing to this result were ALMA, APEX, the IRAM 30-meter telescope, the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope, the Large Millimeter Telescope Alfonso Serrano, the Submillimeter Array, the Submillimeter Telescope, and the South Pole Telescope. Petabytes of raw data from the telescopes were combined by highly specialised supercomputers hosted by the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy and MIT Haystack Observatory.

Achieving “the impossible”

The construction of the EHT and the observations announced today represent the culmination of decades of observational, technical and theoretical work. This example of global teamwork required close collaboration by researchers from around the world. Thirteen partner institutions worked together to create the EHT, using both pre-existing infrastructure and support from a variety of agencies. Key funding was provided by the US National Science Foundation (NSF), the EU’s European Research Council (ERC), and funding agencies in East Asia.

“We have achieved something presumed to be impossible just a generation ago,” concluded Doeleman.”Breakthroughs in technology, connections between the world’s best radio observatories, and innovative algorithms all came together to open an entirely new window on black holes and the event horizon.”