By Julia Solomon

Scholars from around the world are queuing up to study Kitab fi al-adwiyah al-mufradah, a rare medieval pharmacology manuscript housed in the Osler Library of the History of Medicine

Deep within the collections of McGill University’s Osler Library, Kitab fi al-adwiyah al-mufradah — or “The Book of Simple Drugs”— is carefully stored in a dark, climate-controlled room. For an ancient volume that has crisscrossed the globe, passed among many hands, and served as a scholarly resource for some eight centuries, it must seem a pampered life. Despite the quiet surroundings, this unique manuscript is currently generating quite a buzz among researchers from many disciplines and countries.

Abu Ja’far al-Ghafiqi, one of the foremost physicians and scholars of the 12th century, composed this remarkable Arabic text on simple drugs; scholars commonly refer to the work as simply the “Herbal” of al-Ghafiqi. An Andalusian, al-Ghafiqi has long been

recognized by medical historians as the greatest botanist and pharmacologist of his era. He is particularly noted for his exhaustive knowledge of synonyms for plants in many languages, including Greek, Syriac, Latin, Berber, Spanish and Persian. The Herbal is arranged alphabetically according to an ancient notation no longer used in Arabic and contains information on both the identification of medicinal plants and their uses in treating conditions as varied as warts, ulcers and infertility.

The McGill copy of the Herbal dates to the 13th century, and was probably created in Baghdad by a person of high rank. The manuscript contains 367 elegant colour illustrations, mostly of plants, but with the occasional weasel (its stomach repelled vermin), hare (to treat ulcers and kidney stones) and beaver (for the anti-toxin properties of its testicles). Some 90 of these illustrations are particularly important because they depictplants that were unknown to the Greek botanist Dioscorides, whose groundbreaking first-century pharmacopoeia was widely used even in al-Ghafiqi’s time. Though as many as five other copies of the Herbal are referenced in various sources, most of those are incomplete at best (or lost entirely), making McGill’s manuscript the oldest extant copy with illustrations.

Sir William Osler, renowned physician and dedicated collector, sought out this manuscript early in the 20th century through contacts in Persia, though he never realized the full value of his purchase. “Osler acquired the al-Ghafiqi along with another manuscript, believing that he was buying a two-volume Arabic translation of a work by Dioscorides,” says Pamela Miller, History of Medicine Librarian at the Osler Library. Osler paid 25 pounds for the two volumes. It was not until after his death that the truly rare and precious nature of his find came to light.

* * *

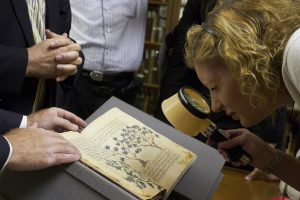

When Miller takes the al-Ghafiqi manuscript out of its cool, dark resting place for viewing, her affection and respect are obvious. Gently paging through the 475 entries, she stops at illustration after illustration, pointing out details in the complex drawings. Some, like wild asparagus and buttercups, are familiar to modern Western

eyes. Others are rarer and more stylized. All are impressive in their detail and thoroughness.

Miller points out features of the text and illustrations, including the high-quality paper, still supple all these centuries later. “At that time, Europeans were still using parchment, which was much more expensive,” she points out, while most of the Middle East had already made the switch to paper. Miller also remarks about the spacing of the text around the illustrations — an indication that they were probably penned later, possibly not by the person who hand-lettered the text — and stylistic differences among the illustrations, which point to the likelihood of more than one artist being involved. With art historians, pharmacists, specialists in ancient texts and other researchers flocking to the Osler library, it’s likely that many of the questions about this manuscript will be answered before long.

* * *

An exploration of the recent flurry of scholarly interest in the al-Ghafiqi manuscript quickly leads to Adam Gacek, faculty lecturer at the McGill Institute of Islamic Studies and former longtime head of the Islamic Studies Library. Gacek chuckles with delight when asked how he became interested in the Herbal. “To tell the truth, it all started with a single word: kabikaj,” he says. Gacek is an expert on ancient Islamic texts, which are sometime inscribed with this word in their first pages. He had devoted some time to studying the roots of the word, which refers to a plant with toxic and medicinal properties, but also sometimes invoked in Islamic texts as a being. So you can imagine his surprise and excitement when, one day, on a tour of the Osler Library collections, he came across an illustration of kabikaj (Rannunculus asiaticus) in the al-Ghafiqi manuscript. (Gacek’s current theory about the inscription of this herb in texts: What likely started as a tradition of pressing an actual kabikaj specimen within the pages of a book — possibly to repel vermin with an appetite for book paste — evolved to simply invoking the protective properties of this plant.) His discovery sparked an enduring interest in the text, and the desire to share it with other scholars. So was born the McGill Ghafiqi Project.

For the Ghafiqi Project, Miller and Gacek collaborated with many scholars across the university, including Jamil Ragep, director of the Institute of Islamic Studies and Canada Research Chair in the History of Science in Islamic Societies, and Faith Wallis, a medical historian in the Departments of History and Social Studies of Medicine. In August 2010, the members hosted a workshop that brought worldwide experts from many disciplines together to study the remarkable manuscript. The team of scholars emerged from the workshop with both momentum and a mandate. Their goal is to produce a three-volume work

derived from the Herbal: a facsimile of the original manuscript, a translation and a collection of scholarly commentary. This new flurry of interest is deeply satisfying to the guardians who have tended the manuscript so carefully since it came into McGill’s possession nearly a century ago.

“We are thrilled at the response that we have received from international experts in the fields of language, art and science,” says Pamela Miller. “This manuscript is a tangible witness of the transmission of knowledge across cultures, and it highlights the central role played by pharmacology down through the ages.”

The Ghafiqi Project workshop was funded by an anonymous gift in memory of the late John Mappin, a Montreal book dealer and collector, and by the McGill Institute of Islamic Studies.