What are your recollections of the Kennedy assassination? Where were you? How did it affect you? How did it change your world? The McGill Reporter is compiling the recollections of members of the McGill community on a tragedy that marked the world. If you would like to share your thoughts in 200 words or less, please send them via email.

By Doug Sweet

I was sitting and probably squirming on a hard wooden chair in a Grade 4 classroom at Duncan McArthur Public School in Kingston, Ont. It was early on a desultory Friday afternoon in November.

“President Kennedy has been shot in Dallas, Texas,” said the first announcement over the scratchy PA. All of a sudden, we were awake.

My 9-year-old brain started to process this information, through the only filter I had for Texas: Kennedy must have been on a horse and he was now slumped over his saddle, bleeding. Not to worry. The good guy always makes it in the end.

Soon, a second announcement. The President was dead. The good guy didn’t make it after all.

This was much harder to process. Dead? How could a president be dead? I barely knew what a president was.

They quickly sent us home from school that afternoon, without really explaining anything (they were probably more shocked than we were) and I remember walking into our new townhouse to find my mother on her knees in front of the television. Weeping. This perplexed me on two fronts: Dallas, on the black and white tube, didn’t look anything like the western saloon towns I had grown up with in the movies, and, why would my mother be in tears about someone she didn’t even know?

Strangely, we had never talked about it much, until just a few days ago. I knew, through the mists of time, how I had felt at that moment and how the event on Nov. 22, 1963, had affected me in subsequent years.

But what had made her cry that day? I didn’t really know, so I decided to ask. She’s 84 and sharp as a tack. Her name is Peggy. She remembers like it was yesterday.

“I had been in a hardware store,” she said. “Probably buying picture hangers or curtain hangers, because we had just moved in. They had the radio going and there was a news bulletin. Everyone just stopped. We dropped what we had. And we all went home.

“All of a sudden, someone had destroyed our world.”

It was a different world and it had been so fleeting and so special. Just how different was not only hard for a 9-year-old to grasp, but also for someone who is today pushing 60, and who had grown up sheltered in the affluent arms of the Baby Boomer generation.

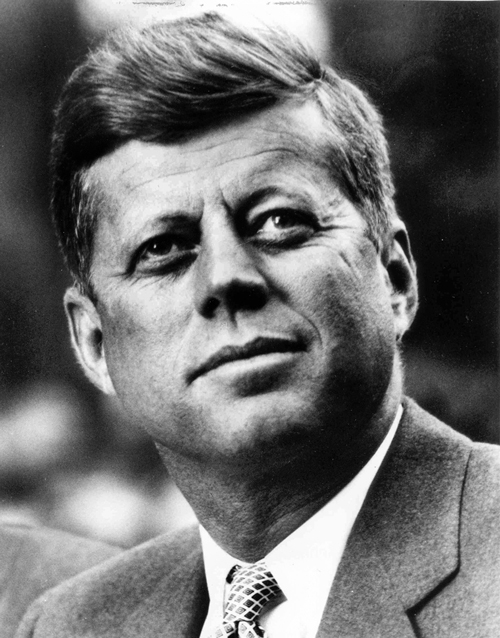

Before Kennedy, there had been no glamour in American politics (or Canadian, for that matter). Perhaps because Franklin Roosevelt had lasted so long in office, only to be followed by such colourless, sexless men as Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower, Jack Kennedy stood out sharply against an otherwise bland canvas.

Kennedy, Peggy said, was “the first one who had been elected on charisma.” He certainly had more of that than his opponent, Richard Nixon, who would go on to spend more time in the White House in a very different era.

And there was Jackie.

“We dressed like her. We did our hair like her,” Peggy said. “It was like suddenly we were all part of a big thing. It was hero-worship like mad.

“They captured something that we had been lacking for a long time.”

For a generation like my mother’s, raised through a Great Depression and a World War, what had been lacking was colour, vibrancy, sexiness and life. “Vig-ah,” to hear Kennedy say it.

Peggy, who was born as the Depression began in 1929, tried to put that in perspective for me.

“I can remember the biggest thing that happened to me when I was just into my teens (as the daughter of an Air Force officer, she was moving from Winnipeg to Halifax). I’d fallen in love with a red coat with a zip-in, zip-out lamb’s wool lining. But it was so expensive.

“It was just before Christmas, and we’d been given seven Christmas trees by people on the base who felt sorry for us.”

There was no coat at Christmas. But in the January sales in Halifax, that coat was on for half-price. It was at Eaton’s.

“And I got that coat. And I wore that coat. I wore it out. You really prized things like that.”

It’s hard to imagine anyone putting such high value on a Canada Goose or a pair of Uggs these days – but that is another polemic for another time.

“The Kennedys came along, the war was over – they were so good-looking … They were not someone we felt belonged to us,” Peggy said.

“I didn’t do any housework or anything that day. I just stayed in front of that television. We had never lived through an assassination. Perhaps because we were able to watch it on TV…

“We felt the world had changed. We were very conscious of evil. We’d had so much faith that things were going to be better. I don’t know why, but we did.”

Faith and hope that were shattered with a gunshot.

This was something I felt more profoundly almost five years later, when Kennedy’s brother Robert was shot in the head in June, 1968, and died in an agonizing pool of blood on the floor of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. I won’t forget that, either, nor the rage that bubbled up when Martin Luther King was gunned down in Memphis only a few weeks before Bobby Kennedy’s death. It was a time of madness.

But the JFK assassination on its own stirred something pretty deep, even in a young kid. All those images. The motorcade. Lyndon Johnson taking the oath of office on an airplane. The funeral and the solo horse. The flag-draped coffin on the caisson. The heart-wrenching salute from John Jr. The eternal flame. Lee Oswald twisting his face in agony as he was shot dead by Jack Ruby. A nation that would never be the same.

If there’s one thing all that did to me, it was to provoke a question that might in turn have steered me to journalism: Why?

Fifty years later, I’m still waiting for an answer.

Doug Sweet is Director of McGill’s Internal Relations Office.

The little-known, but most important clue to the JFK assassination can be found in this Youtube video:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VMuF1u94cic