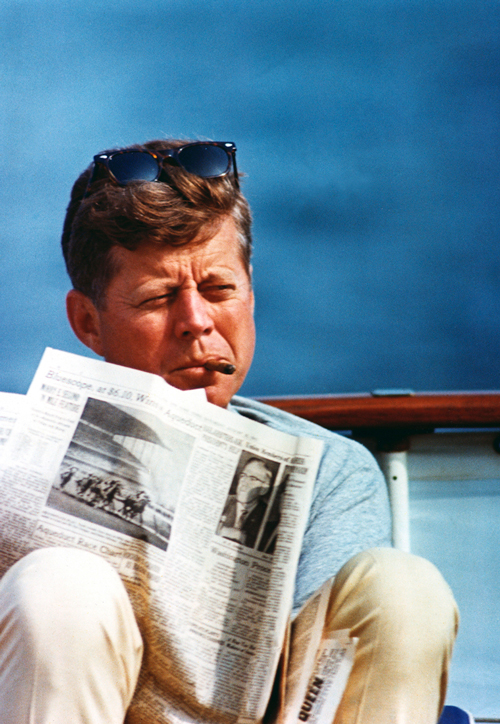

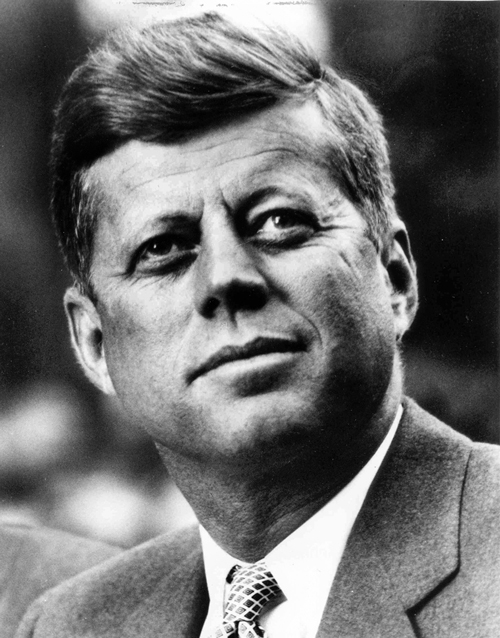

On Nov. 22, 1963, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated while riding in a motorcade in Dallas, Texas, changing the course of U.S. and world politics and marking a generation that had hung its hopes on him. The Reporter asked members of the McGill community to share their memories of that day 50 years ago. Here are there recollections.

****

I was in high school writing a history exam. At the end of it, our teacher announced to the class “…here is something else you can add to your history book…JFK was just shot.” And then on Sunday morning, watching live TV with my Dad, we saw Lee Harvey Oswald, who was being transported by police, get shot by Jack Ruby.

Because of the huge publicity/adoration surrounding JFK and his family which was felt even in Canada, I, too, remember feeling a personal loss.

– Norman Kling, Information Systems Resources

****

I am a McGill alum with a history degree but I graduated in 1992, so the assassination of John F. Kennedy is not something that I directly experienced; however, I do remember researching and writing a history paper on the Warren Commission that opened my eyes to the subject in a deeper way.

Now, as a history teacher, I am revisiting the moment once more. I have asked my Grade 11 students to interview someone who remembers the day. What do they remember? Why do they think the historical moment still has such a hold on us 50 years later? This will be a great opportunity for young students to get involved in an indelible historical moment as it is revisited today.

– James Stewart, BA ‘92, B.Ed ‘94

****

On Nov. 22, 1963. I was a 13-year-old in Vancouver and it was my mother who called my school to report the shooting. Like nearly every school kid in North America, I was sent home, only to receive the news that the President had died. We all watched the events over and over again: Jackie in her pink pill-box hat reacting in horror, cradling her husband’s head in her lap, the motorcade speeding away to the hospital, the Secret Service men running like crazy, guns drawn.

That night I had planned to have a sleepover with another girl on my swim team. We ended up being a whole group of guys and girls in her basement, eating chips, drinking soft drinks and watching the news unfold. We stayed together all night, as some cried, some made useless macho threats against the shooter and some just sat in shocked silence.

That day and night represented to me the crossover into young adulthood, the change from innocence to the cynical and evil world inhabited by adults. The images on our little TV screens brought the whole world in on this tragic event, and marked the dawning of a new digital era where events occur publicly and live.

– Nancy Nelson, Undergraduate Advisor, Biology Dept.

****

I was all too close to it. As a consequence of JFK’s Doctor Draft Decree in 1961, I ended up doing my required two years of military service at the U.S. Naval Medical Center in Bethesda. I checked out early on Nov. 22, 1963, and went to a movie with my wife-to-be at a theatre on Pennsylvania Ave. between the White House and 16th St. Leaving the parking garage in the late afternoon, the attendant broke the news, verified by the Cronkite radio broadcast, and we were devastated. There was the feeling that the world as we knew it was going to be no more without his inspiration.

A few days later I was told I could not access my office or lab at The Tissue Bank of the Medical Center because it would be under high security as the Kennedy autopsy, including the all-important brain part, was going to be done there by experts flown in from New York. Returning to duty the following week, the downcast spirit was present everywhere.

– Ronald D. Guttmann, Emeritus Professor, Faculty of Medicine

****

I was still a graduate student in the Department of Anatomy when my wife called to tell me the news that day. That weekend was spent in front of the TV in horror over the murder of the president, and in real time, the murder of his alleged assassin.

From that day on, I became obsessed with that crime. To this day, with countless books and TV documentaries and state of the art criminology, I remain astounded that no one has seen the obvious; the Zapruder film and the testimony of a witness to the whole shooting, Governor John Connally.

The film is very clear that Connally was not hit by the same bullet that struck Kennedy in the neck. He is hit by another bullet as he turns back toward Zapruder. If this is not obvious to the viewer, why not accept Connally when he says he was not hit by the bullet to Kennedy’s neck, testimony that he gave repeatedly to the Warren Commission and to other inquires. Fifty years on and we still don’t have it right!

– Hershey Warshawsky, Emeritus Professor, Dept. of Anatomy and Cell Biology

****

I spent the morning working in one of the offices on the top floor of Purvis Hall. One of my senior colleagues knocked on the door, and stuck his head in, to announce that Kennedy had been shot. The next two days were spent in front of the TV.

– Antal Deutsch, Emeritus Professor of Economics

****

On Nov. 22, 1963, I was six years old. I have very few concrete memories of that time of my life; just snippets of things, really. But if I have one clear memory of that time: lying on our living room floor watching a news broadcast on television the evening of the day John Fitzgerald Kennedy died.

I remember images from the TV – JFK’s smiling face, a sober LBJ being sworn in. I remember my parents sitting together on the couch, not saying much. I also clearly remember arguing with my older sister about which of the two presidents died – the ugly older one or the good looking younger one.

As I look back at that day, Bev’s refusal to believe that such a vibrant, handsome man could be gone was, in its own small, quiet way, a foreshadowing of the decades of disbelief that followed.

In the 1950s, most Americans believed their government was trying to do good; within a decade that figure had dropped off the map, while today conspiracy groups abound. Some point to 11/22/63 as the trigger of this malaise, and while it may have been, events like the Vietnam war, Watergate, arms for hostages, WMDs, secret renditions, and tapping the cell phones of foreign heads of state suggests that the U.S. government itself – not Oswald – is responsible, not for the death of JFK, but for the death of trust Americans have in their own political institutions.

– Roy Ward, McGill-Queen’s University Press