The Douglas Eating Disorders Program takes aim at anorexia and bulimia

By Neale McDevitt

You’re standing somewhere in the middle of a rooftop and you’re asked to put on a blindfold. Then you’re told to take three steps forward. Like most of us, you’ll be somewhat apprehensive, even frightened, even though you know that you’re nowhere near the edge.

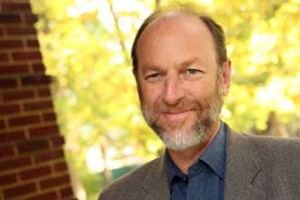

“That’s how people with anorexia nervosa feel,” said Howard Steiger, Director of the Eating Disorders Program (EDP) at the Douglas Mental Health University Institute. “They know they’re thin, but they are terrified that at any moment they could fall over that edge and become fat.”

“People think that anorexics look in the mirror and see a fat person, but they don’t. To over-simplify it, this is a weight-gain phobia problem, not a perception problem.”

The EDP is Quebec’s largest program specializing in the treatment of anorexia and bulimia. Depending upon the severity of each case, patients are treated through out-patient clinics, day hospitals, day programs or within the admission unit.

nd the demand is great. Steiger estimates that upward of 90,000 Quebec women between the ages of 12 to 30 are affected by eating disorders, from full-blown cases to less severe forms that still require treatment.

Faced with these numbers, the EDP waiting list is always in excess of 250 people. “We do a very careful triage,” said Steiger, “so someone with an extremely urgent condition will be seen immediately. But less urgent cases have to wait.”

That’s where the EDP outreach program comes into play. “We can’t treat everyone in Quebec, so we also do as much knowledge transfer as possible with first- and second-line clinicians in the community,” said Steiger. “That way, people on our waiting list can still get informed care.”

The third branch of the EDP mandate (the first two are patient care and teaching) is research. While the group does some work in anorexia, the bulk of their research is centered upon bulimia.

On the surface it may seem like this multi-directional approach would diffuse the focus of the people working at the EDP. Steiger is quick to point out that, in actual fact, this three-pronged approach makes the best use of the group’s talents. “Our philosophy is very much to erase the distinction between care, research and teaching. By being active in research, we stay plugged into new information and we generate new information. That translates into better teaching and, most important, improved patient care.”

Different disorders, similar concerns

Although they express themselves in different ways, both anorexia and bulimia involve intense over-valuation of concerns with eating, weight and body image. In the treatment of either, clinicians must help people re-evaluate the importance they place on things like controlling their weight and their belief that they have to compensate for every calorie they ingest.

The differences seem to lie in the personality traits of the patients. Anorexics are often anxious perfectionists who want to control their environment and who have strong tendencies toward obsessive compulsive behaviour. Bulimics, on the other hand are more prone to impulsivity or dramatic reactivity which, in turn, spurs them on to the cycle of binging and purging. In many ways, the anorexic has the extreme self-discipline coveted by the bulimic.

So what triggers an eating disorder? Contrary to popular misconceptions, the socio-cultural pressure to be thin is only one of the contributing factors. Even more important is the way we are genetically hard-wired and the interaction of our genetic make-up with societal pressures. Simply put, some people are biologically susceptible to developing an eating disorder that, in many cases, is triggered by a traumatic event like childhood abuse or stressors that, though less traumatic, have an equally profound impact.

“Right now we’re looking a lot at the relationship between the serotonin system and eating disorders,” said Steiger. “Serotonin plays an important role as a neurotransmitter of mood regulation, anxiety, social behaviour, impulsivity and satiety. If you muck up the serotonin system, you’re likely to find alterations in people’s moods and their impulse controls which, in turn, makes them good candidates to develop bulimia.”

“Some people are born with lower-level activity of the serotonin system to begin with and dieting only lowers it even more,” continued Steiger. “When people with this type of genetic vulnerability deprive themselves of food, they may trigger a change that had never expressed itself before. Bulimia often arises in family pedigrees where you see a history of depression and other conditions related to low serotonin levels.”

Kinder, gentler therapies

Not that long ago, treatments for eating disorders were often, in Steigers own words, “overbearing.” Patients were forced to eat and coerced into not purging. “Now we treat people from a more respectful position,” said Steiger. “We focus on the psychological factors that influence how motivated a person is to make the change from the inside.”

“We have to help people reach the point where, as scary as it is, they understand that purging is not in their best interest. It’s what we call getting to the

starting line.”

While anorexia has the highest mortality rate among mental health problems, at roughly five per cent, the EDP success rate is very good. Twenty per cent of patients will have some sort of chronic problem for most of their lives but 80 per cent will fully recover or reach a point where their situation is

easily managed.

“We all feel lucky to work here because these are people we can truly help,” said Steiger. “Sure anorexia is startling – emaciated people frighten us. But, as corny as it sounds, we literally see patients blossom into healthy people right before our eyes.”