Children born of wartime rape in northern Uganda endure post-war violence, stigma, social-exclusion

For most people, the end of a war offers relief, hope and an end to violence. This may not be the case for children born of wartime rape, however, who often endure continued brutality in the post-war period.

That finding emerges from a new study of children born to mothers who were abducted, held captive, and sexually violated by members of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a rebel group led by Joseph Kony during the civil war in northern Uganda from 1986 to 2007.

Because little attention has been paid to the perspectives of children born of wartime rape, researchers from McGill University joined forces with Watye Ki Gen, a collective of women who were abducted by the LRA and held in captivity. Together, they interviewed 60 children and youths born within the LRA and currently living in northern Uganda. Participants in the study were between the ages of 12 and 19 at the time they were interviewed. Many had spent their formative years in captivity, ranging from a few months after being born to 7 years.

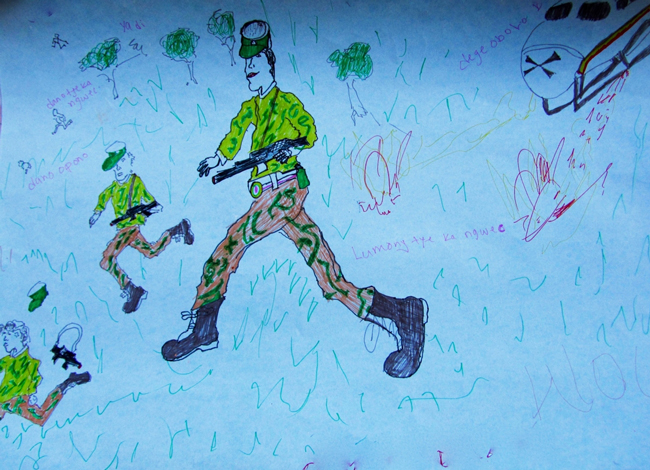

To supplement interviews and focus groups and to enable participants to express themselves in multiple forms, the youth were invited to participate in an arts-based workshop.

When asked to draw their family before and after the war, children often drew themselves and their siblings with sad faces in post-war drawings. When questioned about this, children explained that in many ways they felt their lives were actually better during the war.

This surprising finding, published in Child Abuse & Neglect, is a result of multiple forms of violence, stigma, rejection, social exclusion, and socioeconomic marginalization endured by children born in LRA captivity, explains Myriam Denov, lead author of the study and professor at McGill’s School of Social Work.

“The fact that children and youth identify the state of war and captivity — when violence, upheaval, starvation, deprivation and ongoing terror were at its height — as better than life during peacetime is highly disconcerting and demonstrates the extent of their perceived post-war marginalization,” says Denov, a leading expert on war-affected children and author of Child Soldiers: Sierra Leone’s Revolutionary United Front.

“Life is hard”

Youths interviewed for the study — some of whom shared the same father, LRA leader Joseph Kony—often articulated that “war was better than peace” because during the conflict they felt a greater sense of family cohesion and status within the LRA.

“Life is hard here because people stigmatize us … they have turned their hate against us … In my family, they hate the three of us who were born in captivity … My uncle beats us and said he would kill us. He doesn’t want rebel children, Kony children, at home,” explained one of the participants.

The findings underscore the need for support services to reverse the perception that war is better than peace. Specifically, youths stressed the need for livelihood programs targeting their socioeconomic marginalization, support for school fees, psychosocial support and community sensitization and reconciliation programs.