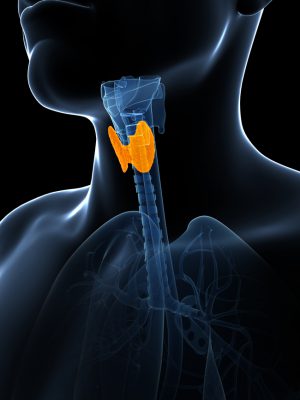

Having an underactive thyroid gland, a condition known as hypothyroidism, is a common disorder that affects an estimated 2 per cent of Canadians. In most of these cases, the problem originates within the thyroid gland itself. Although rarer, in other cases the cause stems from problems with the production or action of the brain or pituitary hormones that control the thyroid. Referred to as central hypothyroidism, this is a condition whose underlying causes have long remained unknown.

A recent study led by researchers at McGill and published earlier this year in the journal Endocrinology has begun to unlock this mystery for what appears to be the most common genetic cause of central hypothyroidism by providing, for the first time, an understanding of the underlying mechanism of the disorder.

Origin story of the discovery

During his time as a postdoctoral fellow at Northwestern University, Dr. Daniel Bernard, now a professor in the Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics at McGill’s Faculty of Medicine and the study’s senior author, began investigating the IGSF1 gene.

“At the time, we thought IGSF1 might be a receptor for a hormone involved in reproduction but our work showed that this was not the case,” explains Dr. Bernard. In 2001, he started his own lab in New York and the IGSF1 project moved with him. “When we discovered that it did not do what we thought, we worked for a while, unsuccessfully, to figure out its true function.”

In 2006, Dr. Bernard joined McGill and in 2007 he recruited a new PhD student, Beata Bak, to work with him on the IGSF1 project. She published one paper in 2008 but then toiled for years trying to figure out IGSF1 function, again unsuccessfully. In the summer of 2011, Dr. Bernard and his student began discussing the possibility that she might have to change projects after four years of working on IGSF1. The conversation was disheartening for both.

A short time later, the student went on a weeklong vacation with her husband. While she was away, serendipity struck. Within the span of that one week, Dr. Bernard received two unsolicited emails from clinician-scientists in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom who had discovered mutations in the IGSF1 gene in two families with unexplained central hypothyroidism. “They contacted me because our lab was the only one working on IGSF1 at the time,” notes Dr. Bernard. “When my student returned from her trip, she had a new and exciting project, and would finish her PhD in the next one-and-a-half years.”

Using mice models to better our understanding

As it was established that IGSF1 is made in the brain and pituitary gland but not in the thyroid, the researchers knew that impairments in IGSF1 function in one or both of these tissues, and not the thyroid, was what was leading to hypothyroidism in these patients.

To solve the puzzle, Master’s student Marc-Olivier Turgeon in the Bernard lab developed a new strain of mice that possessed a mutation in the Igsf1 gene similar to what they observed in humans with IGSF1 mutations. Observing these mice, they were able to identify the principal problem as originating in the pituitary gland.

“The brain secretes a hormone called thyrotropin-stimulating hormone or TRH,” explains Dr. Bernard. “TRH acts on the pituitary gland via the TRH receptor to stimulate secretion of thyroid-stimulating hormone or TSH. TSH then stimulates the thyroid to make thyroid hormones. In our Igsf1 knockout mice, the amount of TRH receptor in the pituitary is decreased, which renders the pituitary less sensitive to TRH from the brain.”

Next steps

The researchers now know that IGSF1 mutations are the most common genetic cause of central hypothyroidism, and some knowledge that provides them with insight into the mechanisms underlying the disorder. Yet many questions remain.

“One thing that continues to surprise us is the heterogeneity of the disorder,” notes Dr. Bernard. “Family members with the same mutation have differing extents of hypothyroidism – some mild, some extreme. Our mice are genetically identical and we still see this heterogeneity. We do not yet have an explanation for this but we are looking for one.”

The next steps for the researchers are to determine the cell and tissue specific roles for IGSF1 and to determine how IGSF1 functions in cells. At this stage, Dr. Bernard explains, “we only know what happens when we lose IGSF1’s function, but this does not tell us what the protein does under normal conditions. This question has haunted us for that past 17 or 18 years.”

Watch the video below