Renowned expert on anti-Hitler conspiracy advised screenwriters

By Mark Shainblum

It would be hard to imagine anyone less Hollywood than McGill history professor Peter C. Hoffmann. At 78, with his neat bowtie and his impeccably polite, old-world manners, the renowned William Kingsford Professor of History is every inch the classic German gentleman-academic. Which is why it’s so difficult to visualize him poring over the screenplay of a blockbuster action movie directed by Bryan Singer of X-Men and Superman Returns fame.

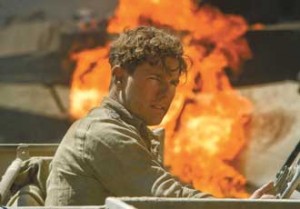

The movie in question, however, is Valkyrie, a World War II action-thriller that opened Christmas Day. Based on a true story, Valkyrie follows a group of idealistic anti-Nazi German army officers who plotted to assassinate Adolf Hitler in 1944. The attempt was led by Colonel Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg, a Roman Catholic aristocrat enraged by the crimes of the Nazi regime that blackened Germany’s honour. Stauffenberg was played by Tom Cruise, who also backed the film in his role as one of the principals of United Artists.

“As far as Tom Cruise is concerned, I did not know him except as the brother in the Rain Man,” Hoffmann acknowledged. “I thought he was very good in that, but I’m not one who goes to action movies, so this was new to me. On the whole, in the fundamentals, I think they have done very well. They have produced a film that is true and accurate.”

Hoffmann is widely considered to be one of the world’s leading authorities on the Stauffenberg plot, so it’s not surprising the writers of Valkyrie relied heavily on his massive 1969 history of the assassination attempt and his later, equally massive biography of Stauffenberg for background material.

“I understand that the scriptwriters glanced at my books from time to time,” Hoffmann said with typical understatement. “And on the strength of that they contacted me and wanted to know if they could talk with me. This went on for a few weeks and then they sent me the script, and asked me to read it.”

“Peter wasn’t an official adviser for the film,” said Nathan Alexander, who co-wrote Valkyrie with Christopher McQuarrie, “but we developed a relationship with him over the course of making the movie. He saw a draft of the script and gave us notes and comments. He was incredibly helpful to us.”

Hoffmann’s lack of official adviser status was by choice, he said. “United Artists offered me a contract, but I said I will not take any money. I want to be free, not a hired brain, and I will tell you what I think. On that basis I was able to press them to include things that I thought needed to be included and to correct things I thought needed to be corrected.”

In particular, Hoffman was adamant that the motives of the conspirators be portrayed in a historically accurate and complete way. Over the years, all sorts of dark motivations have been ascribed to Stauffenberg and his co-conspirators, not the least of which was that they wanted to replace the Nazi regime with an only slightly less odious military dictatorship, or that they were opportunists who only turned against Hitler when it became clear Germany was losing the war.

Such musings were uncharitable and without historical foundation, Hoffmann’s meticulous research showed, and the plotters suffered horribly when the bomb Stauffenberg planted failed to kill Hitler and the abortive coup d’etat fell apart. Stauffenberg and his immediate co-conspirators were summarily court-martialed and shot on the spot, while members of his extended family all over Germany were arrested and imprisoned under Nazi “kith and kin” guilt-by-association laws. Many of them were to die in their cells. Stauffenberg’s brother Berthold and several other members of the conspiracy who survived the coup attempt were tried by Nazi kangaroo courts and sentenced to horrible deaths by slow strangulation with piano wire.

“They were conscious of the very marginal chance of success and that they would probably perish,” Hoffmann said. “And even if they didn’t perish, they had no political future. Regicides can’t be kings. They accepted self-sacrifice as a probable outcome to document their opposition to the crimes the Nazi regime had committed, and to rescue a remnant of the honour of Germany.”

Hoffmann’s research documents that Stauffenberg expressed anti-Nazi and anti-Hitler sentiments as early as 1938, over a year before the war began. By 1941, while Germany was still arguably winning the war, Stauffenberg became aware of the enormity of Nazi crimes against civil populations, prisoners of war and the Jews, and became convinced Hitler had to be removed from power by any means necessary.

“Peter felt it was very important for the film that we get that right,” Alexander said. “His thoughts on the motives of the conspirators against Hitler helped shape the movie we have. We love Peter. He was a huge help and very supportive along the way.”

Hoffmann became interested in the Stauffenberg conspiracy in part because his own father played a role in it, he explains.

“He didn’t make much of it, partly because it had failed, and partly because his was not a leading role, not in the public limelight at all, like Stauffenberg or some of the others,” Hoffmann said. “So he never bragged about it, and there was nothing to brag about. He was just glad that he hadn’t been hanged.”

More generally, Hoffmann explains, his career as a historian has been motivated by fundamental questions about the 12 years of the Third Reich.

“How could it happen? Why did it happen? What course did it run?” he asked. “In fact, I asked my parents, my elders in general, who were there and were voters at the time, how could they let that happen? Of course, they didn’t let it happen, they voted for the Free Democrats, but that’s what got me interested in that period.”

With files from Daniel McCabe.