In 2015, after 122 years of health care and medical innovation, the Royal Victoria Hospital transferred to the McGill University Health Centre’s new Glen site. The move created vacant space to the immediate north of McGill’s downtown campus. More importantly, it also created a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to build a bold new multidisciplinary research and learning centre for sustainability systems and public policy.

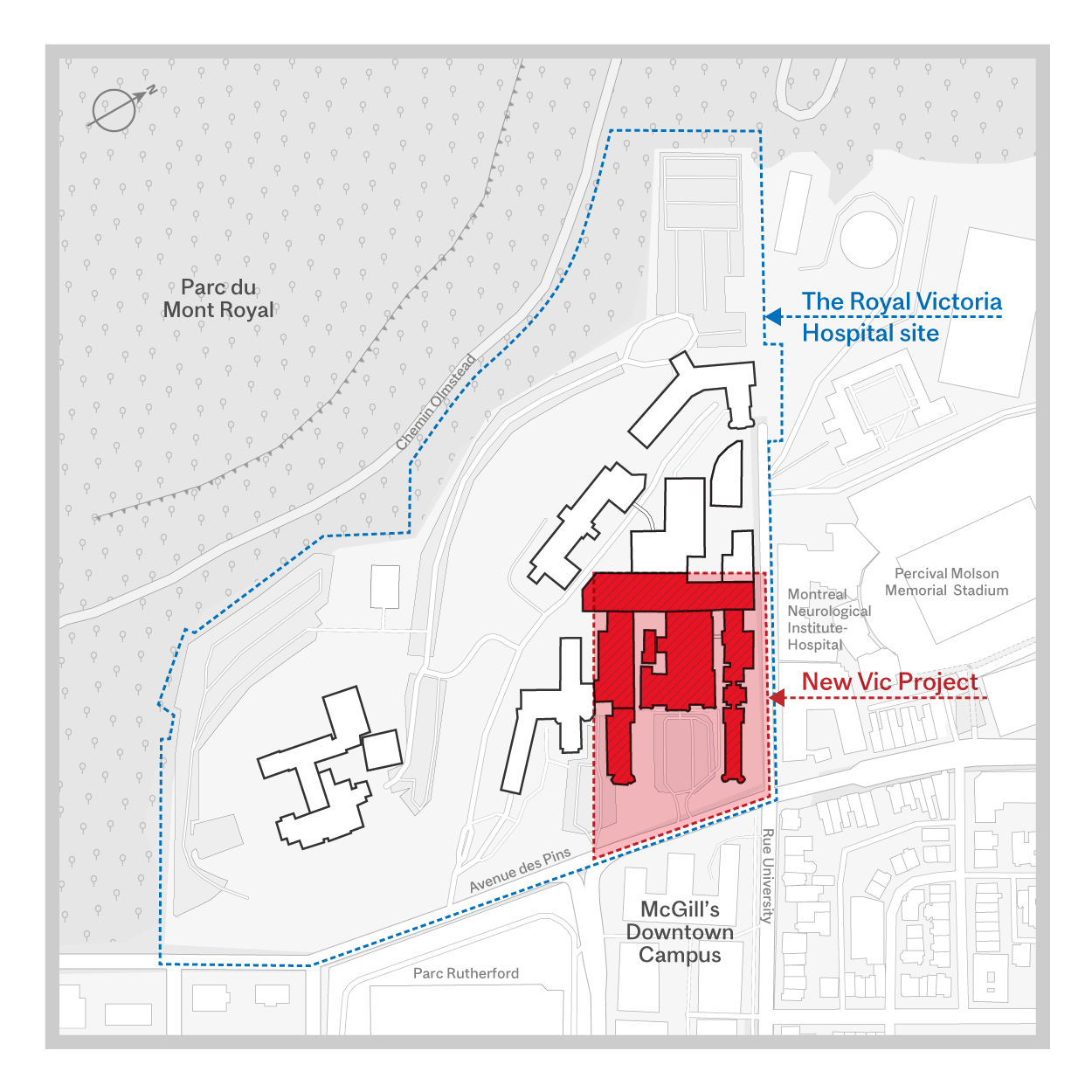

“The Royal Victoria Hospital has been part of Montreal life, and McGill life, for over a century,” says Pierre Major, Executive Director of the New Vic Project, McGill’s proposal to revitalize approximately 15 per cent of the former hospital site, at the corner of University St. and Pine Ave. The Société québécoise des infrastructures (SQI), a branch of the Quebec government, controls the entire 135,000 square metre site.

“We now have the opportunity to rethink how the RVH can play a new role in its relation to the McGill campus, as well as in relation to the city as a whole. The site has a great heritage in health care, and now we have this opportunity to transform it into something that we feel is very much in line with that history.”

The vision

For over a century, the RVH healed people. Now, for its second chapter, it’s going to help heal the planet.

The idea behind the New Vic Project is to transform the main heritage RVH buildings into a mixed-used centre of multidisciplinary education and research that will be anchored by Sustainability Systems (which brings together Molecular–Materials Systems, Earth Systems, and Urban systems) and the Max Bell School of Public Policy.

In 2015, as the new Glen site was nearing completion, Principal Suzanne Fortier struck a Task Force on the Academic Vision and Mission of the RVH Site. The following year, the Task Force released a report entitled “Rethink, Reimagine, and Reinvent.” The report outlined a vision for using a portion of the RVH site to bring together the University’s outstanding strengths in sustainability-focused science and engineering with the social science and policy expertise needed to translate knowledge into real-world sustainability impact.

“Rethink, Reimagine, and Reinvent has two meanings,” says Christopher Manfredi, McGill’s Provost and Vice-Principal (Academic). Manfredi and Vice-Principal (Administration and Finance) Yves Beauchamp are the New Vic’s executive sponsors. “It refers, of course, to the physical site. But more importantly, it’s all about rethinking, reimagining and reinventing the nature of intellectual activity at the University. That second meaning is driven by the recognition that intellectual activity, and the challenges to which it is directed, are no longer predominantly organized around single discipline departments.”

Bruce Lennox, the Dean of McGill’s Faculty of Science and the Academic Lead of the New Vic Project, reinforces the idea that the New Vic will be “an activity-based research and learning site. It’s not about moving departments, it’s about bringing together people engaged in the activity described by the two research pillars: sustainability systems and public policy.”

Indeed, when completed, the New Vic will bring together approximately 150 professors and their associated research groups (representing some 850 grad students and postdoctoral fellows) from 20-something departments across the University. Add in undergraduates attending lectures or studying on site, and support staff, and the New Vic will welcome somewhere in the order of 3,000 people per day.

Integrating new with old

The turrets on the original L, A and E hospital wings, inspired by the Scottish baronial style of the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, are iconic Montreal landmarks. But when it comes to heritage value, not all the RVH site’s buildings carry that same deep cachet.

McGill is interested in reinventing only 15 per cent of the site, an area that is currently home to six buildings. The original L, A and E wings will be carefully restored and reimagined. “The heritage value of the site is really defined by those original 1893 buildings,” says Major. “The dossier d’opportunité pays significant attention to restoring them.”

The M and S pavilions, which were built in the early 1950s and aren’t on par with the majesty of the site’s original buildings, will be removed. The parking lot that is flanked by L, A, and E will be reimagined as a welcoming, open-air forecourt.

The restored heritage buildings will make up about 30 per cent of the New Vic Project, with the balance being new construction designed to respectfully integrate with those heritage buildings.

“The heritage aspect of the site is something that requires a great deal of thought and work,” says Major. “From day one, McGill has recognized its responsibility for ensuring that any new construction is going to support the heritage buildings.”

The target budget for the New Vic Project is $700 million dollars, which include a contribution from the Quebec government of $475 million. The remaining funds will come from the federal government, donations and the University.

The New Vic budget is distinct from the government funding the University receives for maintenance and upkeep of existing infrastructure on the downtown and Macdonald campuses.

Once finished, the new and restored buildings will, together, create 51,500 gross square meters of teaching and learning spaces—including 1,100 lecture seats spread across six active learning classrooms.

The New Vic will be home to five types of state-of-the-art research labs, chosen to maximize flexibility of use: wet chemical labs, two types of process labs, computation labs, and studios.

“We’re building the New Vic for particular research activities,” says Lennox “and the lab typologies are designed to accommodate those different sorts of activities.”

“We have to remember that we’re designing the site for the next generation of researchers as much as we are for the researchers who are already here,” adds Manfredi.

The site will include library facilities, support staff offices, and an event space.

The restored heritage buildings will be incorporated into new light-filled courtyards and interiors that will provide people with many places for informal meetings and engagement. These “collision” spaces are crucial to the New Vic philosophy of stimulating spontaneous interactions.

“In order to bring disciplines together, to bring students together from different areas of degrees in their programs, you have to provide them with that collaborative, interactive, informal space,” says Lennox. “The big sustainability challenges that the New Vic is tackling are not going to be solved by remaining isolated in a disciplinary way. People need to get out of the offices, out of their labs, and meet people from other parts of campus.

“Changing the way that people interact is what we think is really an important part of the future of this university. It’s something that will change how we work as a university, how we teach, how we learn, and how we do research.”

Sustainability built right in

When completed, the New Vic will give a working home to people focused on finding sustainable solutions to the world’s most serious problems—so it’s a no-brainer that the infrastructure project itself will feature advanced standards of sustainable design and construction.

“We’re paying very close attention to this,” says Major. “We’ve made sure that our professional teams include the right expertise to guide us in all the choices that we have to make, and we’ve also made sure that our project budget has the funds to allow us to achieve what we want to do with this.”

One goal is for the New Vic to be entirely heated with clean energy; for example, the project team will soon begin testing the ground surrounding the site to see whether geothermal energy could provide up to 50 per cent of the site’s winter heating needs.

The renovations and new builds will use sustainable building practices, and will meet WELL and LEED Gold building standards. New construction will use waffle slab foundations, which use up to 30 per cent less raw materials than other foundations. When it comes to removing the M and S pavilions, the construction teams will be tasked with meeting McGill’s standard of recycling 75 per cent of uncontaminated demolition materials. Excavation materials will also be recycled. Wherever feasible, salvaged limestone will be incorporated into new facades.

The sustainability mindset will extend to the New Vic’s operations, which Major characterizes as “a living lab” that will gather and analyze data such as how geothermal wells are minimizing fossil fuel consumption, or how an atrium’s green wall is contributing to indoor air quality.

Returning the Mountain to the people

Montrealers love Mount Royal, and with good reason. Inaugurated in 1876, the park is a natural beauty, a marvel of biodiversity, and a year-round playground for young and old alike. As the park’s landscape architect, Central Park designer Frederick Law Olmsted, famously said, the Mountain’s verdant slopes are “the green lungs of the city.”

The New Vic will honour Olmsted’s vision, and Montrealers’ passion for Mount Royal, by better connecting the Mountain with the surrounding neighbourhoods and the downtown core. Over the years, infill construction, such as the M and S pavilions, gradually blocked off access to the park. With their removal, the Mountain will be visible from the University and Pine intersection for the first time in 70 years. On the western side of the New Vic site, a new exterior staircase will take pedestrians—McGillians and the general public alike—from Pine Avenue into Mount Royal Park. Because the site is being built to comply with McGill’s universal accessibility standards, there will also be elevators for people with reduced mobility.

“The architects have worked very hard, very thoughtfully, on how to restore the site’s relationship to the Mountain,” says Major. “We want to bring the Mountain’s presence further into the city.”

“In many ways,” says Lennox, “the New Vic Project is returning the Mountain to Montreal and to Montrealers.”

Honouring Indigeneity

In 2017, McGill University’s Provost Task Force on Indigenous Studies and Indigenous Education set out a series of Calls to Action deemed essential to McGill’s recognition of and reconciliation with Indigenous peoples. Eleven of those Calls to Action focus on physical and symbolic recognition as an important part of addressing McGill’s history and making the campus a welcoming space for Indigenous students, faculty, staff, and community members.

To this end, the New Vic Project’s design will embed Indigenous themes in its public spaces as it balances function with the natural landscape, the site’s heritage, and the recognition that the RVH site has long served as a place of meeting and exchange for the Haudenosaunee and Anishinabeg nations, as well as other Indigenous peoples.

“Recognizing and honouring the Indigenous history of the site is one of the New Vic’s guiding principles,” says Provost Manfredi.

Whether it’s planting rooftop gardens that respect the site’s Indigenous heritage, or respectfully harmonizing the New Vic’s built environment into the natural landscape that is so essential to Indigenous identity, the New Vic project teams will continue to closely consult with both McGill’s internal Indigenous communities, as well as external Indigenous communities.

“We have put a process in place for exchanging with these groups to determine what are the realm of possibilities,” says Major. “The next steps in the next weeks and months will be to pursue this engagement, and come to more clarity so we can provide guidance to our professionals, and incorporate Indigenous physical representation into our documents when we go out to tender for the construction.”

An important piece of a larger puzzle

Although the New Vic Project includes the iconic, castle-like buildings that for many are synonymous with the Royal Victoria Hospital, Pierre Major stresses the fact that McGill’s project involves only a small fraction of a much, much larger site. The SQI owns the complete 135,000 square metre site, which includes the Ross, Women’s and the Hersey pavilions, the Allan Memorial Hospital, and vast grounds.

But just because the New Vic is a small part of the RVH puzzle, it doesn’t mean it’s not important to the SQI’s larger vision for the other 85 per cent of the site.

“The New Vic is just 15 per of the site’s total footprint, but it’s still a key component of the SQI’s overall master plan,” says Major. McGill has worked closely with the SQI to ensure the New Vic plan was in sync with the SQI’s overall vision for the site, making sure height and density limitations, and greening requirements, for example, were respected.

The City of Montreal has translated the SQI’s master plan into a proposed set of bylaws. Although residential housing and hotel projects are off the table, the SQI hasn’t yet finalized exactly what will occupy the rest of the RVH site.

“Of course, our preferred new neighbours would be those that are related to sustainable research and teaching and public policy,” says Major. “We’ve made that clear with the SQI, and we’ll continue to work with them constantly as this project moves forward.”

Long-term planning for the future

A project of the New Vic’s magnitude doesn’t happen overnight. After the Principal’s Task Force developed the project’s guiding principles and themes, McGill worked with the SQI to develop a dossier d’opportunité (DO) that outlines the University’s plans. More than a year in the making, the DO is 1,400 pages of technical architectural renderings and layouts, all in the context of the New Vic’s academic plan. The Quebec Government approved the dossier d’opportunité in May 2021.

The project’s next milestone is a dossier d’affaires (DA). McGill’s Board of Governors will render a decision for the New Vic Project to proceed to the DA development phase when it meets next month. Once completed, the DA goes to the Quebec government for approval in the spring of 2022.

Following the Quebec government’s approval of the DA, the New Vic will break ground in 2022, with a grand opening projected for 2028.

Hello

A question I forgot to ask earlier is what about bicycle parking. I am thinking about interior, access controlled parking for year-round use. Is there any on campus, and is there any plan to integrate bicycle space into this or other renovations going on around the campus?

Heidi, Plans call for about 150 spaces for bicycles. Roughly half would be covered.

Fantastique! Love that the old Vic will be maintained and transformed into the new Vic. I recall the majesty of those historic buildings…walked by everyday when I lived in Molson Hall residence so many decades ago. Even got to visit the Urgence Santé once…seriously dated interiors. The proposed open air courtyard looks spectacular with its mesmerizing ovals of light…reminiscent of Calgary’s new public library (home for me). Miss McGill and Montreal. Cheers.