By MUHC Staff

In 2012, and again in 2013, two separate outbreaks of tuberculosis occurred in communities of northern Quebec. “The affected communities prefer not to have a spotlight shone on them,” says Dr. Marcel Behr, director of the McGill International TB Centre and RI-MUHC researcher, “since tuberculosis is a very sensitive issue. They need solutions more than they need attention.”

Concern for anonymity is not unusual for people with tuberculosis: in Canada it is the only disease for which a person can be incarcerated for refusing medical treatment. For at least the past two centuries, tuberculosis has been a persistent medical and social issue. It is a very adaptive disease that resists all attempts to eradicate it, and questions about its origins, spread of infection, treatment and social impact persist.

So why are communities in northern Quebec – and indeed in many areas in both the first world and developing nations – still suffering outbreaks? How is it possible that the disease continues to infect and cause the deaths of people in Canada? What are the social and fiscal costs associated to managing the disease?

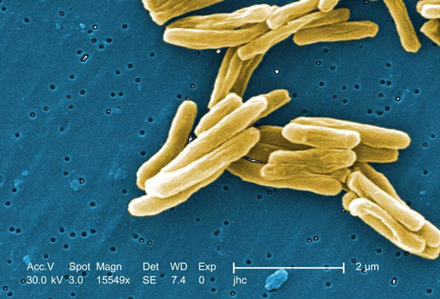

“That’s what we’re trying to discover,” says Behr. “The McGill International TB Centre’s mission is to study tuberculosis, its spread, its social impact on health. The centre brings together experts in fundamental research, clinical research and epidemiology.” The centre also studies a range of other mycobacterial diseases.

“This is a worldwide problem with very important social implications, and those affected live in first world and developing nations alike,” says Behr. “Worldwide, we record about nine to ten million new cases each year, and tuberculosis is responsible for about 1.4 million deaths every year.”

The centre was formed “organically” from an informal group of researchers in Quebec and Ontario who were already studying tuberculosis, but it recently banded together to build a formal research centre. This approach has many advantages, such as the ability to share resources, as well as take advantage of certain team grants not normally available to individual researchers. The centre currently counts over 20 researchers in four major institutions: McGill University, the University of Ottawa, the University of Montreal and the Institut national de santé publique du Québec.

The research also has an international scope, involving contributions from fellow academics from over 30 countries. This collaboration is essential because the capacity to treat and manage tuberculosis is currently undergoing a heavy challenge: without new tools and approaches, tuberculosis will continue to kill one person every 22 seconds.

According to Behr, “the McGill International TB Centre is examining a wide range of foundational, clinical, epidemiological and societal questions surrounding this disease.” These include: what are the host genes that help us to resist tuberculosis infection? What role does vitamin D play in immune response? What is importance of different strains of the bacteria? And how should governments and healthcare providers manage costs associated with the disease?

“The truth is we are very humbled by the ongoing prevalence of this disease, so we think it is best that we study it without making any prior assumptions,” Behr says. “Hopefully we will discover something that helps us overcome this worldwide challenge.”

To know more about the McGill International TB Centre go here. For those who missed it, you can watch the discussion of the Café scientifique “TB: Portrait of a global killer” held on March 21 by clicking here.