“There are just so many stories tucked away along with the plants in an herbarium,” said Heather Rogers (MA, Digital Humanities ’23) as we sat in the bright spring sun outside the McGill Herbarium to chat about her work bringing the story of the influential curator out of the protection of the cabinets and into the light – virtually that is – preserved plants being rather sensitive to UV radiation.

Rogers has taken her research on Dorothy Newton Swales (BSc Plant Pathology, 1921; MSc Bacteriology 1922; PhD University of Manitoba, Mycology 1931) and transformed it into an interactive website so that others can follow the six decades of botanical collections made by the herbarium’s first woman curator (1964-1971) and longest serving mentor to young botanists.

Frozen flowers as teaching aids

After completing her PhD at the University of Manitoba in 1931 (the first woman to do so), Swales came back to Ste. Anne-de-Bellevue and McGill’s Macdonald College, as it was then known, to lecture in botanical sciences. She strove for excellence in her teaching, trying hard to bring her students the experience of connecting with plants in nature.

Not wanting to merely show them illustrations from books, she developed a technique of teaching from frozen flowers, so that students could see for themselves during the cold months of the academic calendar what a species would look like fresh. It is a teaching tradition I carry on at Macdonald Campus to this day.

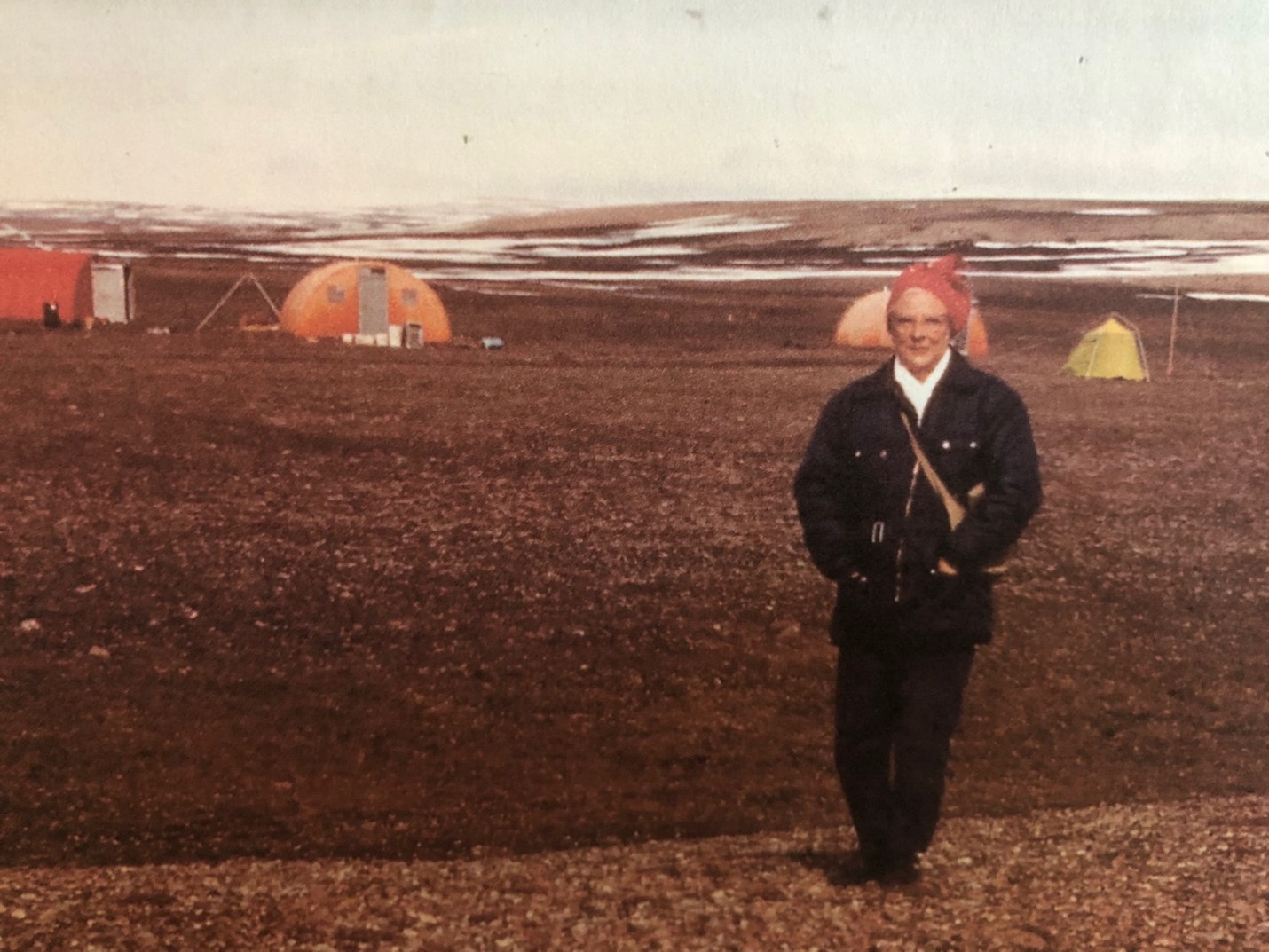

In the summer months she often went with students to the arctic regions of Canada, expanding the scope of species in the collection with each trip. She struck up friendships with arctic botanists in Norway and the former USSR, trading specimens to build a truly circumpolar collection.

The secret life of plants unveiled

“The stories are not just of the plants, but the people who collected them, preserved them, described them. The labels tell the story of where they were collected, what was growing alongside them, who determined their identities. The messy entanglements inspire us to look deeper and closer at the natural world. Reciprocity, symbiosis, mimicry, communication, are some of the ways I frame interactions within the natural world with what are usually considered human traits – which are really not unique to human societies at all,” explained Rogers on her approach that draws on the field of Critical Plant Studies and places agency on the plants to have a story of their own to tell.

I asked Rogers in what ways her own story has become entangled with that of Dr. Swales.

“I never really knew much about arctic plants and when I thought of the artic, I thought of it as a place that was so hostile to flowers and green plant life,” said Rogers. “Learning about that flora through Swales and how they’re a backbone for arctic ecosystems, for example how these plants create microclimates for pollinators. In her notes on summer travels to Iqaluit, Swales remarked that ‘much of arctic beauty and interest lies in the ‘microhabitat’, or the small things you discover at your feet.’ Now when I think of the arctic I think of the incredible resilience – which is such a human word-of these plant communities. They are small but they make life possible, so much relies on them for their existence. And also I totally fell in love with lichens.”

Nice work!!!