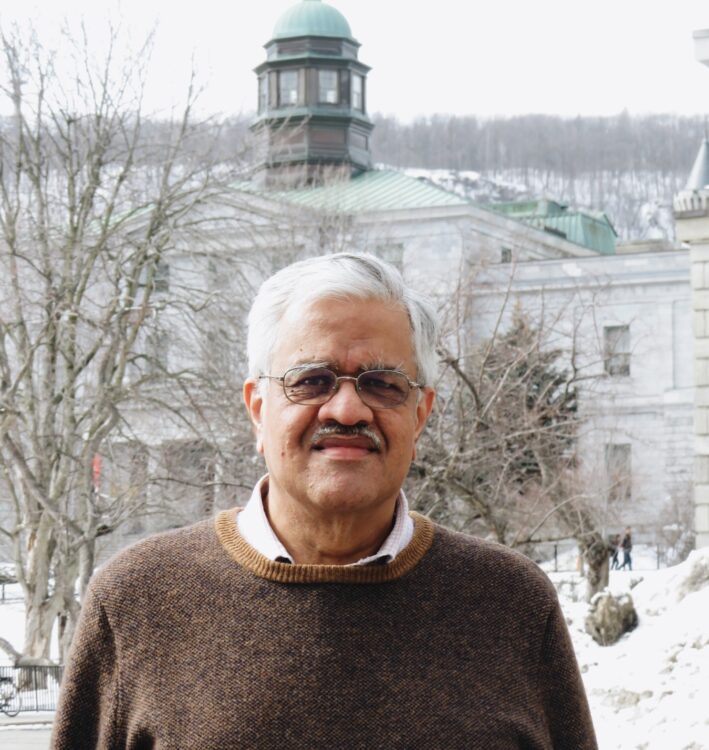

One of the greatest strengths of the McGill Environment Studies program is its emphasis on interdisciplinary work, and Madhav Badami, PhD, is no exception.

Badami began his career in mechanical engineering, but his drive to make a change in the world led him into teaching at McGill’s School of Urban Planning and the Bieler School of Environment. Through his work in and outside the classroom, Badami is able to share his ideas of collective action and learning for the future with hundreds of students every year.

On top of this, his involvement with the Sustainability Projects Fund (SPF) connects him with initiatives on all corners of our campuses. The SPF is the largest fund of its kind in Canada, valued at $1 million annually, and has the mandate to build a culture of sustainability on McGill’s campuses through the seed funding of interdisciplinary projects.

Badami shared his unique pedagogy in a sit down with the Office of Sustainability.

As an instructor, you are tasked with introducing students to the topic of the environment in their first years of study. What are some of your philosophies about teaching learners about sustainability?

There are various kinds of knowledge and analytical skills that are useful for understanding issues related to environment and sustainability, and to address them effectively. Because these issues involve scientific-technological, but also socio-economic, political-institutional, human behavioural, and ethical dimensions, I draw on perspectives from multiple disciplines to investigate them along these dimensions.

I also demonstrate the importance of addressing these issues [through the lens that] people really matter. This means, firstly, trying to understand – with humility – why people make the choices that they do in relation to resources and the environment.

Secondly, in order to develop and implement policies that are effective and equitable, I discuss the importance of carefully considering how people might be affected by and will likely respond to them.

Lastly, because these issues are characterized by multiple groups in society with conflicting interests and concerns, and a range of impacts that affect these groups differentially, I discuss collaborative approaches for reconciling these interests and concerns, and conflicts and trade-offs between these impacts from the perspective of various groups.

I use case studies to show the usefulness – and limitations – of the theoretical concepts and analytical approaches I discuss, and real-life examples from a range of contexts of the challenges in addressing these issues, and how they were surmounted.

You also just finished your mandate on the SPF Governance Council. Can you tell me a bit about what you enjoyed about your role there?

I think that the SPF is just terrific and it’s allowing a lot of really good work to happen at McGill. It’s great to see students and staff from different units across the University coming together to propose very interesting projects that aim to solve various sustainability-related issues on campus.

My participation on the Governance Council has been an enjoyable but also educational experience for me. We get the opportunity to evaluate these funding proposals in terms of their environmental, socio-economic and equity aspects, as well as their feasibility and their potential for long-term impact.

I particularly love that the council is made up of faculty, staff and students from different units across the University. As I said, you need to include a wide range of perspectives on these issues, and that is precisely what ends up happening in these council meetings.

Your position is unique in McGill in the sense that your involvement is not bound to one school. What has working between departments allowed you to do in terms of sustainability? Do you believe that this collaborative approach is more effective in tackling environmental and social issues?

I think it’s a really exciting place to be. My joint appointment in the School of Urban Planning and [the Bieler School of] Environment, both of which are highly inter-disciplinary fields, allows me to interact with people working on a wide range of issues from various perspectives. But even more importantly, it allows me to engage with students from a range of backgrounds. For example, in my graduate environmental policy and planning class, I have students in urban planning and environment, but also from the sciences, engineering, international development, law, urban systems, bioresource engineering – you name it – who come together to learn about and work on these important issues. It creates an amazing mutual learning experience for both myself and the students.

The issues we are dealing with in the world right now…. You can’t just put them in a disciplinary box. You need to integrate perspectives drawn from multiple disciplines in order to really understand and address them effectively. This is not to say that work on these issues within disciplines is not important — we absolutely need these efforts to find solutions – but there are certain aspects of sustainability that you just can’t understand without looking at the whole picture. It’s not “either-or”; it’s “both-and.”

As someone who is so integral to sustainable education at McGill, what message do you want to share with the McGill community?

Just because you aren’t in environmental studies doesn’t mean you don’t have a place in sustainability. If I had been asked 20-30 years ago if I could have ever imagined that I would be where I am today, I would have said, “Not in my wildest dreams.” I encourage you to find the best way that you can develop your own nuanced way of thinking about these issues that reflect their complexity and share them whenever you can.

Secondly, moral concern – and even outrage – is important, because it helps you move towards action. I want to emphasize the importance of hard thinking, as [American ecological economist] Herman Daly did many years ago, to focus on coming up with practical, feasible ways to reconcile different affected groups in society.

Along with moral outrage, I also want to emphasize the importance of realistic optimism. Yes, there are all kinds of challenges, and the solutions are not going to be easy, but it’s important to remember that positive change is possible, and in fact, it’s happening right now.