By Katherine Gombay

It looks like something from an old science fiction movie – a black glove covered with lights and hanging wires.

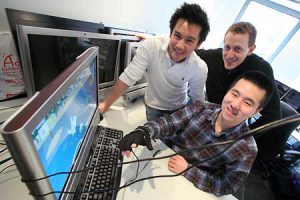

In fact, the glove is the result of a research experiment for the development of a new tool to help stroke victims recover hand mobility as they play custom-designed video games. The biomedical sensor glove, which was developed by a group of McGill mechanical engineering students, is designed to be hooked up to a computer that relays data about a stroke patient’s progress directly to the treating physician. The glove allows patients to exercise in their own homes with minimal supervision, while at the same time permitting doctors to monitor them from a distance. Patients can monitor their progress thanks to software; which will generate 3D models and display them on the screen while at the same time sending the information to the treating physician.

This means that as well as being a tool in stroke patients’ rehabilitation, the glove could also potentially lower medical costs by reducing their number of hospital visits.

The device was developed in response to a request from the start-up company Jintronix. Justin Tan, the company’s CEO, is the moving force behind the glove, a project that he’s been working on for the last six years. He got the idea while working on his undergraduate degree in biological engineering at MIT. For a class project, the students were asked to develop a medical device.

Because of the high prevalence of stroke in Southeast Asia, where he was born and his family still lives today, Tan was immediately drawn to the idea of creating a device for stroke rehabilitation. And at about the same time, his reasons for working on the project became even more compelling. “My father had a stroke right around this time, while on a plane from New York to Paris, so I became very passionate about that aspect of health care. Over time, as I walked him through the paces of his rehab, I got really familiar with the strengths and weaknesses of the services for stroke patients.”

Having completed his engineering degree at MIT, and a Masters in Public Health from Cambridge, Tan has now enrolled in studies in medicine at McGill, because he feels that without a complete understanding of the biological basis underlying specific conditions, it’s going to be difficult for him to apply his engineering skills effectively in the health care domain.

Jintronix started out as what Tan characterizes as ‘a passion project.’ “It was basically just a group of students who were interested in using the knowledge that we gained in class to build something that’s useful for society,” said Tan.

The company is made up almost entirely of students – eight out of the nine are either current or former McGill students in fields that range from engineering, to medicine and finance. The company came into being when Tan, working with Shawn Errunza, a friend of his since high school, held information sessions at university campuses in the fall of 2010 to recruit others who might be interested in contributing to the project. It was incorporated last year in order to apply for funding for project development.

Tan’s ultimate goal is to use both his clinical and engineering backgrounds to develop new technologies and systems designed to help people get better. Why not? It seems to fit like a glove.