By Jenna Senecal

“Janah!”

That’s Jossum greeting me. Everyday after work I stop by Sophie’s shop to see my friend – every time he greets me with the same enthusiasm and his wide smile. We chat a little about the day, what he studied at school or which village I visited today; but then I continue home to prepare dinner. Then I return to the shop when it is dark – after my dinner and my washing up – it’s around seven o’clock.

“Janah!”

I sputter out my few Chichewa phrases to Jossum and he tries to teach me some new words.

“Do you want to play shop?” Jossum asks.

“Yes!”

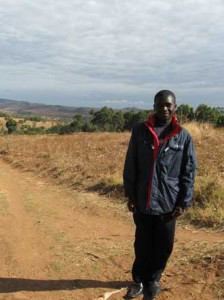

I have come to Ntchisi, Malawi, in southern Africa as a volunteer through Engineers Without Borders – Canada. During the day I work with a local Malawian NGO: Work for Rural Health. The project’s goal is to reduce the number of diseases in children under 5 through improved hygiene and sanitation practices.

Malawi is one of the most densely populated countries in southern Africa, with an average annual income of about $800 a year ($2.19 a day) and high infant mortality and HIV/AIDS rates which result in a low life expectancy of about 43.5 years.

During the evenings, I hang out at the kiosk with Jossum. My co-worker, Dellings, owns the kiosk and his wife, Sophie, manages it.

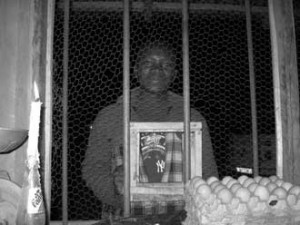

Jossum crawls out of the shop through the half door and I enter the same way. I’m sitting on small wooden bench. There is room for the two of us to sit, but I am alone inside and unsure if it would be culturally acceptable if we were both sitting here together. The floor on which the bench and my feet are resting is made of old cracked clay, and for a few minutes my bench is a rocking chair.

The only door to the room is the two and half feet tall by three feet wide entrance I crawled through – it takes you right outside. The same wall with the door has wooden boards on the bottom half and chicken wire on the top. There is a hole in the chicken wire – large enough to pass items out for exchange of Kwacha, but small enough that someone can not reach in and take more than a handful of items at a time.

Where the wooden boards change to chicken wire there is a counter – full of goodies on a good day: bread, eggs, sugar, gum, biscuits; empty, except for a few batteries and super glue on a poor day. Today is a good day. The three other walls all have shelves with more goodies – soap, matches, dried fish, Tasty Soy Pieces, Fanta and Coca-Cola. But even on good days these shelves are never full.

The only light is a candle. The outside is completely dark – no street lights, only the stars. I can only make out Jossum’s silhouette eating the banana I brought for him. A rare treat, as the market in Ntchisi is very small and I can find bananas only at bigger trading centres.

There is a small radio on the shelf, playing a local gospel song; the batteries are weak and the signal is not strong, more static than music. I cannot hear or see people until they are right there, right in front of me. Little kids always make me jump.

Jossum starts talking – talking in his broken, but now more confident English – he shares his vision, his wishes to go to college, to get a degree, to get a job, to not live like this anymore. And how this job will not get him there.

“Fanta.”

“40 Kwacha,” I reply.

It’s Moose Man, he wants a Fanta – I call him Moose Man because he always wears the same shirt with a moose on it and I don’t know his name. Yesterday he asked me to buy him a Fanta; today he is asking me to sleep with him. He is drunk. He leaves.

Jossum starts talking again. “People see you – ‘Ah, I want to talk to that girl – but how? How? I do not speak good English.’ So they do not know what to say and they are too shy. What comes out is ‘Give me money’ or like what ‘Moose Man’ said. But they are just joking, they just want to talk, they just want to be your friend.”

Eight o’clock comes and it’s time to close the shop. I return home to write in my journal, read and sleep. Jossum returns to Sophie’s house – he is the house boy and his day’s work is not finished. He washes the dishes from the family’s dinner (if the water is on) and washes their shoes.

He eats dinner, maybe watches a little TV with the family, but then retires to his room to study. He wakes up early, at about 5:30 a.m., to start mopping and preparing food. At 7:15 he leaves for secondary school, Form 3 (our Grade 11) and returns at 2 to eat lunch. Then he goes to the market to pick up things for Sophie’s Shop, crawls through the half door in the shop and turns on the radio.

“Janah!”

I’m walking home from work and Jossum calls out to me. I tell him that tonight I will be the shopkeeper and he will be the student – that he can now go home to study. He looks at me like I’ve given him a million kwacha.

But it will take more than a kind gesture and a night free to study to get a houseboy in Malawi into university.

Jenna Senecal is a U3 student in Bioresouces Engineering. She is currently President of the Engineers Without Borders – McGill, Macdonald Campus Chapter and has just returned from a three-and-a-half-month placement in Malawi, Africa. For more information you can contact Jenna at president_mac@mcgill.ewb.ca or check out the web site at www.ewb.ca

Sidebar: How Jossum dreams of going to college

Jossum is from a small village in Ntchisi district and is living here so he can attend school. His father passed away when Jossom was very young, leaving his mother to raise five children. He is third, and the only one to have gone to high school. Primary school is free (Standard 1 through 8), but Secondary is not (Form 1 through 4). So Jossum had to work very hard to get himself through the first two years. Molding bricks, building toilets – every time he got paid, he’d walk to the school to put the money toward his tuition. He was recognized for his efforts and Red Cross Malawi now pays his school fees. The work he is doing at Sophie’s is for room and board – he is not paid any Kwacha.

During his break between Form 3 and 4, he will find another job in hopes of saving money for college. But he is worried; college is very expensive: 100 000 MK (about $750) per semester – with few scholarships and little chance of a bank loan. He will find a job but it will pay between 2,000 – 6,000 MK a month. It will be a long time before he can go to college. He has asked me for help…