By Katherine Gombay

Disasters such as floods, tsunamis, and earthquakes often result in the spread of diseases like gastroenteritis, giardiasis and even cholera because of an immediate shortage of clean drinking water. Now, by using paper coated with silver nanoparticles, McGill chemistry researchers have taken a key step toward making a cheap, portable, water-filtration system to be used in these emergency situations.

“Silver has been used to clean water for a very long time. The Greeks and Romans kept their water in silver jugs,” said Prof. Derek Gray, of McGill’s Department of Chemistry. But though silver is used to get rid of bacteria in a variety of settings, from bandages to antibacterial socks, no one has used paper-based silver systematically to clean water before. “It’s because it seems too simple,” affirmed Gray.

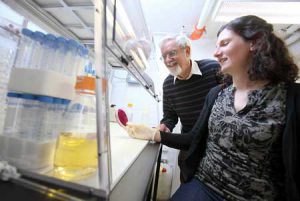

Gray’s team, which included graduate student Theresa Dankovich, coated thick (0.5mm) hand-sized sheets of an absorbent porous paper with silver nanoparticles and then poured live bacteria through it. “Viewed in an electron microscope, the paper looks as though there are silver polka dots all over,” said Dankovich, “and the neat thing is that the silver nanoparticles stay on the paper even when the contaminated water goes through.”

The results were definitive. Even when the paper contains a small quantity of silver (5.9 mg of silver per dry gram of paper), the filter is able to kill nearly all the bacteria and produce water that meets the standards set by the American Environmental Protection Agency.

The filter is not envisaged as a routine water-purification system, but as a way of providing rapid, small-scale assistance in emergency settings. “It works well in the lab,” said Gray, “now we need to improve it and test it in the field.”

Gray and his team are currently developing an even “greener” version of the filtration system, a process that has definite side benefits. “It smells like caramel and everyone comes round to find out what we’re doing,” said Dankovich. “I’m having a really good time working on it.”