Pension plans are a hot topic these days. It is estimated that almost half of all Quebecers don’t have an employer-sponsored pension plan. For those who do, pension deficits are an even hotter issue. Deficits everywhere have rapidly accelerated over the last decade or so, and they have spiralled since the 2008 financial crisis. But what factors contribute to pension deficits in the first place? Here, John D’Agata, McGill’s Director Pensions & Benefits, sits down with The Reporter to answer our questions about what makes or breaks a pension deficit.

How does a pension plan run into deficit?

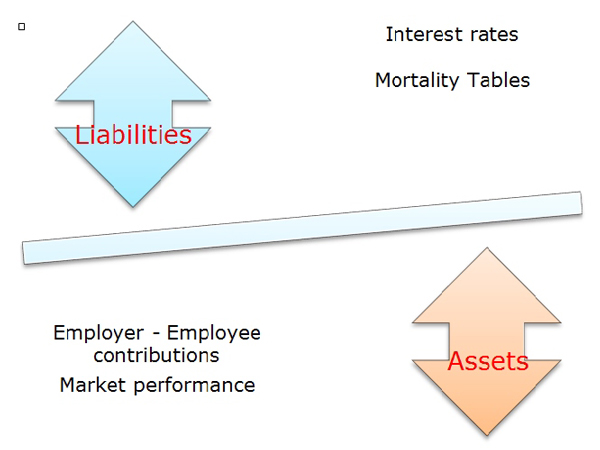

Pension deficits are caused by a series of interacting factors. But to simplify it, you could say that there are four main factors at play:

- Investment performance, which determines the appreciation/depreciation of your investments as it affects the market value of your assets, i.e., lower investment returns reduce the growth in the value of your pension holdings.

- Interest rates, which are used to determine your pension liabilities, i.e., lower interest rates mean payments to departing members increase.

- Employer-employee contributions, which define the amount of money that is regularly going in to fund the plan.

- And mortality tables, which define longevity and are used to estimate the average number of years plan members will collect their pensions.

To understand this interaction, we can classify these main factors as assets vs liabilities:

It is the balance, over time, between these main factors that mostly determines the health of a plan: assets must cover liabilities or, in other words, there must be enough money in the pension plan to fully pay out retirement/termination settlements, present and future. If however, over time, your liabilities exceed the value of your assets, the plan is out of balance and it will start to run into a deficit. Equally, gains made in one of the factors may be offset by losses realized in another. For instance, market gains may be offset by lower interest rates or improving longevity, ultimately resulting in increased deficits.

How have those factors played out at McGill to create our current deficit?

Our situation is very similar to those of most employers who offer pension plans in their benefits package.

On the assets side of the equation, investments experienced more volatile returns over the last 10 years. In addition, prior to 2013, employee contributions had remained the same since the plan was created in 1972. At the same time on the liability side, average life expectancy has increased over time, resulting in pensions being paid out for longer than was originally forecast. In addition, interest rates have stayed at historical lows, increasing our pension liability. Overall, the liability side of the equation began to outweigh the asset side. McGill’s Pension Administration Committee has for many years been looking at ways to make the pension plan more sustainable in the long-term.

The global financial crisis of 2008-09 changed the investment climate completely. Investment returns plummeted. Since then, markets have remained volatile, which continues to create a difficult environment for pension plans across North America.

We implemented numerous changes at McGill with various effective dates to restructure our plan and make it viable. The most recent change came into effect in January of this year, introducing cost-sharing of deficits between the University and those employees who are part of the hybrid segment of the pension plan (also referred to as part A, which includes a defined benefit minimum component).

It has been recently reported that the University finished last fiscal year with an operating surplus and that a big chunk of that surplus was due to a $12.5 million pension liability reduction. What does this mean concretely?

Some could interpret this as meaning that our extra pension contributions are used to create an operating surplus. This is not the case.

Favorable market conditions allowed our investments to perform better than anticipated, but the $12.5-million figure was calculated for accounting purposes to close our books for the last fiscal year, 2013-2014. This type of calculation currently differs significantly from valuations we must do to determine how we must fund our plan to keep it sustainable in the long run. Such valuations are called funding or “going-concern” valuations. In short, an accounting valuation doesn’t give a picture of the long-term health of a plan, as does a funding valuation. By law, funding valuations are triggered every three years. Our next funding valuation will be completed by December 2015.

New government accounting rules which are being introduced will soon allow funding valuations to be used for accounting purposes. This should eliminate the major discrepancies resulting from these two types of valuations and how they are applied. In fact, with these new accounting rules we expect that the University’s financial statements next year will show an increase in the amount of the pension liability, painting a more realistic picture of the pension plan deficit.

So, while a $12.5 million drop in the pension liability, based on current accounting valuation calculations, has been reported in McGill’s financial statements for last fiscal year (2013-2014), this figure does not affect the funding requirements for the long-term health of our pension plan.

Since markets have performed better, can members expect their extra contributions to go down?

Right now, contributions to the plan are based on the last funding valuation, which was done in December 2012. The next funding valuation will be completed by December 2015. Any revisions to our contributions must await the results of that new funding valuation.

While markets have performed better last year, this improvement represents one side of the ledger. In the December 2015 valuation, the Canadian Institute of Actuaries will factor in public sector Canadian mortality tables as opposed to previously used North American ones. This will increase our plan’s liabilities. And we are already anticipating that this increase will offset the gains we were able to realise on the assets side of the equation through our extra contributions and last year’s market performance. To know exactly by how much, we will have to wait for the results of the next valuation exercise scheduled for no later than December 31, 2015.

This is why it would be premature for us to consider decreasing our current employee-employer contributions or to modify the deficit cost-sharing provisions.