By Jim Hynes

Does Bilingualism Have a Future in Canada? Le bilinguisme a-t-il un avenir au Canada? Participants at a conference organized by the McGill Institute for the Study of Canada (MISC) commemorating the 50th anniversary of the launch of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism pronounced themselves on that question – in English, French…and Mohawk, before a packed house in the Faculty Club ballroom on Wednesday.

The event was co-sponsored by the University of Ottawa and the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages as part of a national lecture series they launched to commemorate the Royal Commission chaired by Le Devoir publisher André Laurendeau and Carleton University president Davidson Dunton in 1963. The resulting recommendations ultimately resulted in the creation of Canada’s Official Languages Act in 1969.

Together with representatives of the University of Ottawa and Concordia University, Commissioner of Official Languages of Canada Graham Fraser was on hand to deliver words of welcome at the event.

Some participants at the event celebrated Canada’s official bilingualism policy while others condemned it.

In the event’s first keynote address, Pierre Curzi, the actor and former Parti Québécois MNA and language critic known for his controversial views on Quebec’s anglophones, said French needs to be “the common language of Quebec” and that official bilingualism had created several negative aspects in the province, but that it also succeeded in ridding French Canadians of “the anglo minority who owned us.” Curzi, now a member of the provincial Option nationale party, pointed out that the official bilingualism policy had at least succeeded in making Quebec anglophones bilingual, but also said that he doesn’t consider that group be a minority in Quebec, but rather an “extension of the anglo majority in the rest of Canada.”

Curzi took aim once again at one of his favourite targets, anglophone Montrealers who “hold a disproportionate economic and political power” that “padlocks the electoral system” and “puts the brakes to what would normally be happening.”

During the panel discussion that followed, Indigenous human-rights activist, Ellen Gabriel, who delivered her opening remarks her native Mohawk, cited the “collective amnesia” of Canada’s two solitudes and bemoaned the fact that protecting English and French had come “at the cost and expense of indigenous languages across Canada.”

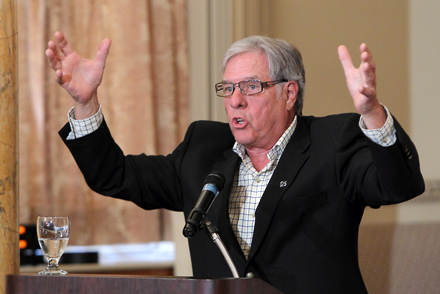

Panelist Warren Allmand, a longtime MP and a former cabinet minister, human rights activist and lawyer, and the current President of the World Federalist Federation – Canada, made the distinctions between official, institutional and individual bilingualism before enthusiastically endorsing the future and importance of all three: “Yes, yes, and yes.”

Other panelists included, actress producer and entrepreneur, Fabienne Colas, Concordia French Studies professor Sherry Simon, and McGill Associate Professor (French Language and Literature), Catherine Leclerc. The discussion was moderated by CBC Radio One host Bernard St-Laurent.

Before painting a positive portrait of the current state of English and French in both Quebec and the rest of Canada in his closing keynote, former federal Liberal leader, Stéphane Dion, whose father Léon was a special research advisor to the Royal Commission, celebrated the civil manner in which the discussions of the day took place.

“When an actor we love came and told you, with humour, kindness and courtesy, that your language had no place in the public sphere and public institutions, and there was not a single word of protest or interruption, and everyone listened politely…” Dion said. “Having seen how language debates take place elsewhere in the world, I can tell you, this is possible only in Canada and it makes me love my country even more.”

A video recording of the event will soon be available on the MISC website.

To read a McGill Reporter Q&A interview with Graham Fraser, click here.