Mice and rats stressed by male experimenters; reaction may skew research findings

By Chris Chipello

Scientists’ inability to replicate research findings using mice and rats has contributed to mounting concern over the reliability of such studies.

Now, an international team of pain researchers led by scientists at McGill may have uncovered one important factor behind this vexing problem: the gender of the experimenters has a big impact on the stress levels of rodents, which are widely used in preclinical studies.

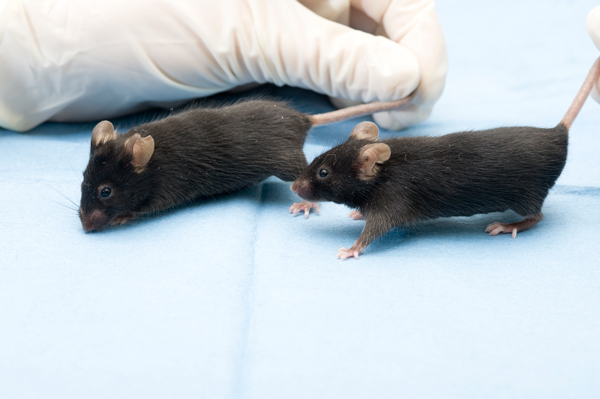

In research published online April 28 in Nature Methods, the scientists report that the presence of male experimenters produced a stress response in mice and rats equivalent to that caused by restraining the rodents for 15 minutes in a tube or forcing them to swim for three minutes. This stress-induced reaction made mice and rats of both sexes less sensitive to pain.

Female experimenters produced no such effects.

“Scientists whisper to each other at conferences that their rodent research subjects appear to be aware of their presence, and that this might affect the results of experiments, but this has never been directly demonstrated until now,” says Jeffrey Mogil, a psychology professor and senior author of the paper.

The research team, which included pain experts from Haverford College and the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden and a chemosensory expert from Université de Montreal, found that the effect of male experimenters on the rodents’ stress levels was due to smell. This was shown by placing cotton T shirts, worn the previous night by male or female experimenters, alongside the mice; the effects were identical to those caused by the presence of the experimenters, themselves.

Further experiments proved that the effects were caused by chemosignals, or pheromones, that men secrete from the armpit at higher concentrations than women. These chemosignals signal to rodents the presence of nearby male animals. (All mammals share the same chemosignals).

These effects are not limited to pain. The researchers found that other behavioural assays sensitive to stress were affected by male but not female experimenters or T-shirts.

“Our findings suggest that one major reason for lack of replication of animal studies is the gender of the experimenter – a factor that’s not currently stated in the methods sections of published papers,” says Robert Sorge, a psychology professor at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. Sorge led the study as a postdoctoral fellow at McGill.

The good news, Mogil says, is that “the problem is easily solved by simple changes to experimental procedures. For example, since the effect of males’ presence diminishes over time, the male experimenter can stay in the room with the animals before starting testing. At the very least, published papers should state the gender of the experimenter who performed the behavioral testing.”

“Olfactory exposure to males, including men, causes stress and related analgesia in rodents” can be read here.