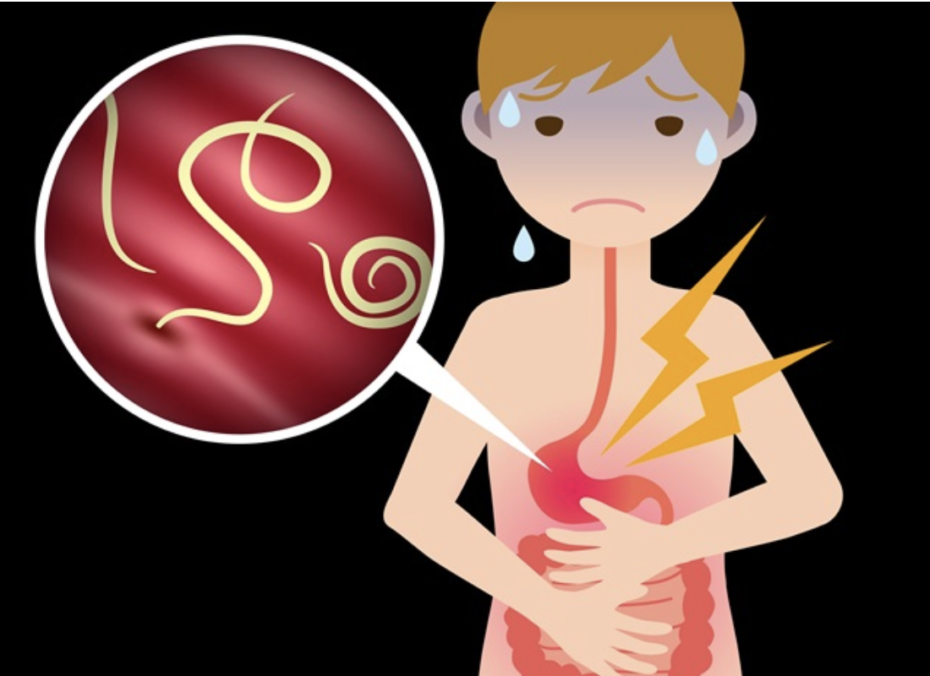

Canadians may bring parasitic intestinal worms back as unwanted souvenirs from travels abroad. But for more than one billion people in Asia, Africa and Latin America, they are more constant companions. Helminth parasitic worms, such as roundworms and hookworms, spread through fecal contamination of the soil in areas lacking effective sanitation and waste management. Chronic infection is associated with anemia, diarrhea, malnutrition, stunted growth and impaired cognitive development.

Canadians may bring parasitic intestinal worms back as unwanted souvenirs from travels abroad. But for more than one billion people in Asia, Africa and Latin America, they are more constant companions. Helminth parasitic worms, such as roundworms and hookworms, spread through fecal contamination of the soil in areas lacking effective sanitation and waste management. Chronic infection is associated with anemia, diarrhea, malnutrition, stunted growth and impaired cognitive development.

Dr. Theresa Gyorkos, Senior Scientist in the Infectious Diseases and Immunity in Global Health Program at the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre (RI-MUHC), has dedicated her career to understanding and reducing the harms caused by parasitic worm infection.

“The key,” she explains, “is to eliminate fecal contamination by a combination of treatment and improved household sanitation and hygiene,” a goal the World Health Organization (WHO) hopes to achieve by 2030. Until that happens, Gyorkos, who is Director of McGill’s Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Research and Training in Parasite Epidemiology and Control, is focused on getting treatment to people living in the 100 countries where infection in endemic.

Global deworming program

In the late 1990s, Dr. Gyorkos began working with WHO towards establishing new guidelines for periodic deworming. A resolution adopted in 2001 by the World Health Assembly recommended preventive treatment for high risk groups, particularly school-age children. A WHO-coordinated global program was put in place with technical guidance and support provided to endemic countries.

“It’s amazing to see hundreds of kids in a schoolyard lining up for deworming tablets,” says Gyorkos, “especially when you consider all the layers of government that need to work together to get deworming treatment to 600 million schoolchildren.”

Most endemic countries have established deworming programs for children in schools, which provide a ready-made infrastructure for distributing treatment and promoting prevention. The supply of deworming treatment for the WHO-led program comes entirely from donations from two drug companies, in the form of single-dose tablets; one company has even developed a chewable tablet for young children. Within each country, governments and program managers organize distribution and undertake periodic monitoring to check that the program is working to reduce worm burdens. A more recent focus is now on treating women of reproductive age to prevent anemia in mothers and low birthweight in babies.

Impact of climate change and spread of parasites

Gyorkos’s research efforts began in Canada, with studies of South-East Asian refugees arriving in the late 1970s and 80s. “The government was considering the need to screen people for worm infections, but we found the infections were self-limited and, because of our effective waste management systems, local transmission would not occur.” Another major accomplishment was a complete review of human parasites occurring in Canada, finding that some are shared with other circumpolar regions.

“We’re now looking at the impact of climate change on these parasites and their transmission,” says Gyorkos, who is also a Professor in McGill’s Department of Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Occupational Health.

Her research abroad, notably in the Amazon region of Peru, documents the impact of worm infections, the safety of treatments and the best ways to reach people. In a study published in 2018, Gyorkos and colleagues found that chronic worm infections at a young age affect cognitive and verbal abilities as well as physical development. In 2019, she published a systematic review of risks associated with deworming treatment in pregnancy, finding no increased risk, even during the first trimester. The WHO program, however, remains cautious about treating for worm infections in early pregnancy, preferring to rule out women in early pregnancy and instead, offering them deworming treatment at a later time. Gyorkos’s most recent study, which will appear shortly in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, evaluated how this ruling out can be done as efficiently as possible. “As a research community,” Gyorkos emphasizes, “we contribute the evidence on which WHO can base their guidelines.”

When we spoke, Dr. Gyorkos was reviewing drafts of the WHO strategic plan to 2030, pleased that the McGill Collaborating Centre had been renewed for a second four-year term. The Centre testifies to the Canadian research community’s responsiveness to global priorities, and Gyorkos’s own commitment to mentorship and support for global health researchers worldwide. The hallmark of success? “I’m generating all kinds of interest in worms!”