Researchers, CLUMEQ computers aid in breakthrough international experiment

By Chris Chipello

Early on the morning of July 4, officials at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, announced that they had discovered clear signs of a new particle consistent with the long-sought Higgs boson – the so-called God particle – whose discovery would support the prevailing theory of how elementary particles acquire mass.

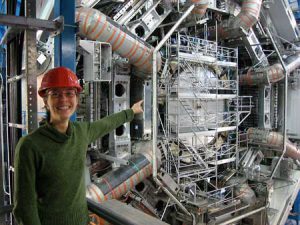

The much-anticipated announcement in Geneva, Switzerland, was carried around the world, and set off a whirlwind of media interviews in Montreal for Physics Prof. Brigitte Vachon. Vachon is one of several McGill researchers who are members of the ATLAS international collaboration – one of two multi-purpose CERN experiments (the other is known as CMS) involved in the search for the Higgs boson.

(See a Q&A with professor Vachon below)

Meanwhile another member of the McGill team, Prof. Andreas Warburton, was busily spreading the word about the CERN results from Melbourne, Australia, where physicists from around the world were gathered for this year’s major particle physics conference. The announcement of the CERN findings served as a curtain-raiser for the conference, and Prof. Warburton was among the scientists helping to distill the highlights via Twitter.

In a memorable scene after the ATLAS and CMS teams wrapped up their presentations, Prof. Peter Higgs, the theoretician who had set off the decades-long hunt for the elusive particle, congratulated the researchers. Warburton captured the moment in this tweet: ‘Peter Higgs: “Incredible that this has all happened in my lifetime.” ‘

The McGill research group also includes professors François Corriveau and Steven Robertson. The group has contributed directly to the development and operation of the ATLAS detector trigger system responsible for selecting in real-time the small fraction of collision data to be further analyzed, as well as performing data-taking shifts in the control room of the experiment and contributing to various data quality tasks. “All of this work benefits the entire collaboration and has a direct impact on all physics measurements,” including the results announced July 4, Vachon explains.

In addition, a significant fraction of analysis jobs that led to the preliminary results announced in Geneva were performed at the CLUMEQ-McGill high performance computing centre which acted as a host site for ATLAS data files and provides computing resources to analyze the volumes of ATLAS data. CLUMEQ is the research consortium for high-performance computing that includes McGill, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec network.

Both the ATLAS and CMS experiments at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider accelerator reported observing a new particle in the mass region around 125-126 GeV consistent with the Higgs boson. The McGill researchers are among hundreds across Canada who played critical roles in this breakthrough.

“We observe in our data clear signs of a new particle, at the level of 5 sigma, in the mass region around 126 GeV. The outstanding performance of the LHC and ATLAS and the huge efforts of many people have brought us to this exciting stage,” said ATLAS experiment spokesperson Fabiola Gianotti, “but a little more time is needed to prepare these results for publication.”

Five sigma corresponds to a certainty that the odds are less one in 3.5 million that this observation is simply produced by chance.

More than 150 Canadian scientists and students are involved in the global ATLAS experiment at CERN. TRIUMF, Canada’s national laboratory for particle and nuclear physics, has been a focal point for much of the Canadian involvement that has ranged from assisting with the construction of the LHC accelerator to building key elements of the ATLAS detector and hosting one of the ten global Tier-1 Data Centres that stores and processes the physics data for the team of thousands.

Likening the quest for the Higgs to Christopher Columbus’s voyage of discovery to the New World, Nigel S. Lockyer, director of TRIUMF, said, “With ATLAS and the LHC, we set sail in the direction toward what we thought was the land of the Higgs. Last December, we saw a smudge on the horizon and knew we could be getting close to land. With these latest results, we’ve seen the shoreline! We know we’ll make it to dry land, but the ship is not in to shore just yet.”

The results presented today are labeled preliminary. They are based on data collected in 2011 and 2012, with the 2012 data still under analysis. Publication of the analyses shown today is expected around the end of July. A more complete picture of today’s observations will emerge later this year after the LHC provides the experiments with more data.

“We have reached a milestone in our understanding of nature,” said CERN Director-General Rolf Heuer. “The discovery of a particle consistent with the Higgs boson opens the way to more detailed studies, requiring larger statistics, which will pin down the new particle’s properties, and is likely to shed light on other mysteries of our universe.”

Q&A on the Higgs boson with Prof. Brigitte Vachon

Shortly after the CERN press conference in Geneva on the morning of July 4, the Science Media Centre of Canada – a nonprofit organization that helps journalists cover science news – sent Prof. Brigitte Vachon a set of questions to help explain the findings and their significance. Here are the Centre’s questions, and Prof. Vachon’s answers:

Has the discovery of the Higgs boson been announced?

Preliminary results showing strong evidence for the existence of a new particle with a mass of approximately 125 GeV have been presented. These results are called preliminary since they have not yet been published, something that should happen approximately by the end of the month (July). The data analyzed so far suggest that this new particle resembles the long-sought Higgs boson. There is only a probability of one in about a million that the observation of this new particle is simply produced by chance.

If not, what more needs to happen data-wise to do so? When will this happen? If so, why is this significant for the Standard Model?

The hypothesis that there exists in the universe a so-called Higgs field that permeates all space is a cornerstone of the Standard Model of particle physics. The consequence of this theoretical hypothesis is the existence of a particle called the Higgs boson. The existence of this Higgs field in Nature would explain why matter has mass. More than a generation of physicists have searched for the Higgs boson. The discovery of a Higgs particle would be one of the biggest discoveries in the field in over a generation. It will not only strengthen our theoretical description of Nature but also provide guidance in where to look in our data to try to answer other fundamental questions such as the nature of dark matter.

How confident are we that this is the Higgs boson? Are there any surprises in the particle’s behavior?

The data collected so far only allow physicists to take a glimpse at the new particle which seems to exist. Precise measurements of its properties in order to confirm whether this is in fact the long-sought after Higgs boson will take many more years. Having said that, the little that we know so far about the behaviour of this new particle, it appears to indeed resemble the Higgs boson.

What else is significant about this data that should be noted?

What should be noted is that this observation is the result of an extremely large amount of work by many thousands of scientists world-wide. It is a perfect example of a successful international collaboration. It is very hard to convey the amount of effort and all the resources (human and technical) that has gone into making this measurement possible. Many thousands of people have contributed in their own way to this incredible success. The challenge of sifting through all the data collected is exceptional; it amounts to a greater challenge than seeking a needle in a haystack. And it could only be achieved with the dedicated work of thousands of scientists.