By Neale McDevitt

On Dec. 29, 2009, UCLA staff research assistant Sheharbano “Sheri” Sangji suffered extensive burns to nearly half her body in a chemical fire that occurred when the syringe full of t-butyl lithium she was handling exploded into flames. Eighteen days later, Sangji died of her injuries. She was 23 years old.

During the lengthy legal battle that ensued, after chemistry professor Patrick Harran was charged with four felony counts of “willful violation of an occupational safety and health standard causing the death of an employee,” it became clear this was a tragedy that could have been averted.

And could have happened anywhere.

“It was a horrible, horrible tragedy,” says Wayne Wood, McGill’s Associate Director, Environmental Health and Safety (EHS). “And something as simple as a lab coat could have saved her life. In incidents like this, we’re seeing a distinctive pattern where the Principal Investigator (PI) wasn’t necessarily engaged in the students affairs or reviewing the safety assessments and risks and making sure things are being taken care of. There’s a gap there.”

Public outcry for stricter safety standards

If there is any measure of solace to come out of the UCLA incident, it is that it has sparked a very vocal public outcry about the need to be more rigorous in the application of safety standards in labs and in holding people and institutions accountable for the safety of their employees.

For example, this year’s McGill Safety Week, from Sept. 8-12, is largely focused around the matter of individual responsibility.

“Here at EHS, we’re really emphasizing the University’s Internal Responsibility System (IRS),” says Wood. “Everyone is responsible for health and safety – from students to the Principal to members of the Board of Governors. Whether it be on the individual level to follow the rules and protocols the University has established; or to report the hazards that confront us on our day-to-day activities here; or for people with supervisory responsibilities who are legally responsible to make sure that their students and employees are duly informed and equipped to safely do the work – safety is everybody’s business.”

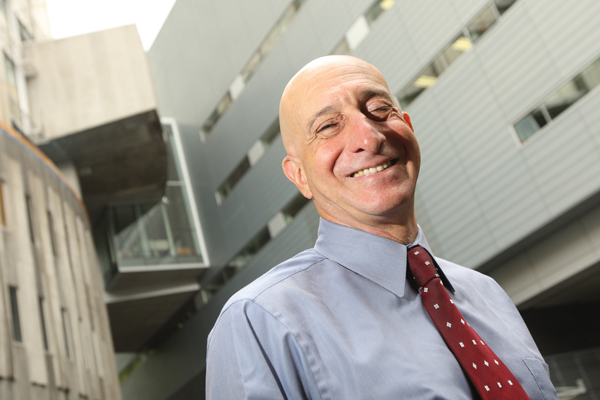

While following safety protocols and donning protective gear in labs would seem as logical as putting on a seatbelt in a car, some PIs are guilty of ignoring both. The big obstacle, says Alvin Shrier, of the Department of Physiology, is changing the culture in some labs.

“When you start a job at a company in the private sector, you walk in and they say, ‘Here are the rules. If you want to work here, follow them,’ ” says Shrier, Chair of the University Laboratory Safety Committee and a researcher with more than 30 years managing a lab. “But until recently, when you came in as an academic, you barely knew there were any rules at all.

“Over the past five to 10 years, the rules have become a lot more clear-cut, but we still see a lot of people – especially some older faculty members who are probably less informed about those rules and less likely to enforce them in their labs. And if your PI isn’t wearing a lab coat, what message does that send to the other people working there?”

Message comes from the top

While Wood agrees with Shrier that one of the big hurdles is overcoming the old-school attitude among some PIs, he believes any significant change must start from above. “I’ll come right out and say it, sometimes there is a gap at the level of the Chair of the department,” says Wood. “I don’t want to generalize because many Chairs are very good but some of them are ill-equipped because they aren’t necessarily trained in the responsibilities that come with being a manager or an employer.

“And this can carry right to the Deans,” continues Wood. “Some Deans are very isolated from health and safety issues and may be under the false impression that things are going well because no issues have come across their desk.”

But silence is not necessarily golden when safety is concerned. Many breaches in protocol or hazardous situations go unreported for a variety of reasons. Some people don’t like being the bearer of bad news or feel intimidated by their department head. Others don’t want to draw negative attention to the lab or have a cavalier attitude about potentially dangerous situations simply because they’ve gotten along without incident… for now.

“Safety is one of those things that if you don’t manage it, it’s going to bite you, and sometimes it’s going to bite you bad,” says Wood.

Another common excuse for not making a request to improve a potentially dangerous situation is that people believe recent budgetary constraints don’t allow for meaningful upgrades in safety measures and equipment.

Nothing could be further from the truth says Wood. “Michael di Grappa [Vice-Principal, Administration and Finance] has repeatedly told the community that while certain initiatives have to be postponed or cancelled because of budgetary concerns, health and safety is not one of them,” he says. “The senior administration is fully committed – and if they are committed to health and safety, it only makes sense that the people in the labs are as well.”

Critics decry ‘slap on the wrist’

Back in California, prosecutors maintained that Sangji never received adequate training to handle the highly volatile t-butyl lithium, a pyrophoric that ignites spontaneously in air. On the job in Harran’s lab for several months prior to the accident, Sangji had never even been issued a lab coat, which might have helped lessen her injuries when she was hit by the fireball. Instead, the synthetic material of her sweatshirt burned quickly, only adding to the severity of her wounds.

Harran’s lawyers painted a different picture, contending that Sangji – who had earned a bachelor’s degree in chemistry five months earlier – was an experienced chemist who chose not to wear protective clothing and had received proper training for the experiment.

The contentious nature of the case came to a head earlier this summer when Harran struck a deal that all but frees him from criminal liability. Instead, under a “deferred prosecution agreement,” he will perform 800 hours of non-teaching community service in the UCLA Hospital system, and pay $10,000 to the Grossman Burn Center in lieu of restitution to Sangji’s family.

Many people, including academics, criticized the settlement as being a slap on the wrist.

McGill’s Safety Week runs from Sept. 8-12. For more information and the complete schedule, go here.