Undergraduate course reaches out to those with a disability

By Neale McDevitt

If, as Goethe once wrote, “our earthly ball [is] a peopled garden,” then McGill’s Adapted Physical Activity course offers a blueprint for successful cultivation. Take a class of Kinesiology and Physical Education undergrads, pair them with a person who is intellectually challenged; plant the seeds of compassion, trust and fun; add a little pool water; and watch it bloom spectacularly.

“I wanted to give students the opportunity to help a person with a disability to reach their goals,” said Education professor Greg Reid when asked why he started a ‘lab’ with the Adapted Physical Activity course 30 years ago. “I thought our McGill students needed to get their feet wet and use these techniques that I had been blabbering about in class.”

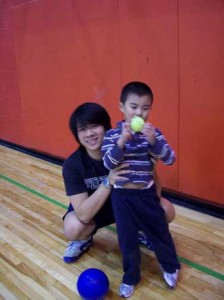

Every Wednesday during the semester, about 100 people with an intellectual disability converge on the McGill Sports Centre where they follow a physical activity program designed and supervised by a McGill student. The interaction is one-to-one, with the same pairings working together over a 10-week period. For the past two years, the course has been overseen by PhD candidate Cathy MacDonald.

With ages ranging from five to 55, each activity program is specially designed for each individual. “Our students are responsible for assessing their partner, setting objectives, prescribing a program and evaluating throughout whether objectives were met,” Reid said. “Because there are no set guidelines that will magically work for everyone, the emphasis – and really what being an educator is all about – is on problem-solving.”

The activities range from basic physical skills such as running, jumping and climbing for the very young to full-blown conditioning programs for the older participants who often have very clear fitness goals. Throughout it all, the McGill students act almost as personal trainers.

Aside from the obvious physical benefits, participants also make huge gains in self-esteem. “Physical education is a normalizing skill,” said Caryn Schacter, Principal of REACH, a school in St. Lambert for 60 people aged 4-21 with moderate to severe intellectual challenges and developmental delays. “We’ve had so many kids learn to swim at McGill, we can’t even count. And swimming is a transferable skill. Our kids can go to the local pool and swim with the other kids. It makes them feel more autonomous and part of the community.

“Wednesdays at McGill are always the highlight of the year for us. The kids just love it.”

But the life lessons aren’t strictly for the participants who are bused in every week. “If this was an optional course, a lot of McGill students wouldn’t take it because there is always a fear of the unknown,” said Reid. “By the end, however, most feel very proud of, and I would say even fulfilled by what they’ve accomplished.”

Schacter agreed. “Of course, we gain a whole lot from the program, but I also think the McGill people develop a new sensitivity.”

For all the friendships formed during the course, the last day isn’t always easy. “Some of the kids have real issues at the end,” said Schacter. “But the McGill people go out of their way to make the ending so nice. They give the kids mugs, t-shirts; pictures, letters – the bonds they create last for years.”