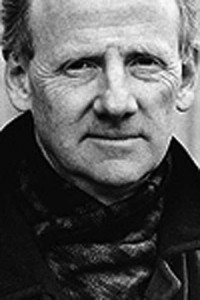

By Pascal Zamprelli

“The problem,” contended John Ralston Saul, “is that we act as if it wasn’t true; we act as though there is not an aboriginal tradition that is central to the law. We refuse to consider the idea that we do things here that are creations from here. We are missing the essential debates, because we don’t see the originality.”

Saul delivered the McGill Law Journal’s annual lecture Tuesday night before a packed house in the Faculty of Law Moot Court, which drew largely on themes from his most recent book, A Fair Country.

“Canada is built on three founding pillars,” he said, but “the original pillar has been virtually ignored,” despite having contributed in major ways to the Canada we know today. “It’s not some romantic historical thing about something that happened in the past,” he said, “it’s actually the foundation on which this society is built.”

Saul was eager to point out instances of aboriginal influence in the legal sphere, using a ubiquitous concept today – legal aid – as an example. When John Turner was Minister of Justice about 40 years ago, Saul said, he visited courts in the Northwest Territories, only to find a very different legal reality and learn that “this wasn’t a cash economy, that justice here was not a money business, and that lawyers weren’t going to be paid.” As a result, the government developed a system of legal aid for the territory, an idea that eventually spread across the country.

“That’s where legal aid was invented,” Saul said. “And it was invented not in order to deal with poverty or a class society, not to mirror European theories of helping the poor. It was created in order to deal with and mirror an aboriginal reality of Canada, which is to say a co-operative, non-financial society with an oral legal tradition.”

Saul also drew links between aboriginal ideas and Canadian multiculturalism, common-law marriage, immigration and citizenship policy, and single-tier healthcare, as well as larger concepts of egalitarianism and non-violence. He feels this influence, however, is rarely consciously recognized, much less formally recognized. He said that in struggling to try and trace every element of the Canadian reality back to European ideas, we are in fact selling ourselves short, and obscuring history. “It’s as if we hadn’t done one thing here that had a relationship to ideas that are endemic to this place,” he said.

Saul praised Canadian courts for integrating aboriginal theories into treaty cases, for example. But why not introduce these concepts – homegrown ideas – into more traditional legal cases, he asked, calling on the legal community, and the population at large, to rethink the sources of Canadian society. “What does

the relationship mean, and what is the role of aboriginals at the core of Canada, and therefore at the core of Canadian law?” he asked. “There’s enormous philosophical and legal work to be done.”