Anatomy of an agricultural tsunami

By Neale McDevitt

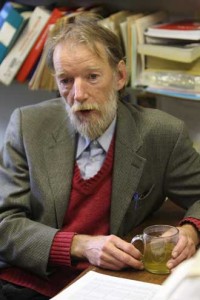

Earlier this year, rising food prices triggered riots around the world, including in Haiti, Yemen, Burkina Faso, Bangladesh, Cameroon, Ivory Coast and Indonesia. To get an expert opinion on how the current food crisis came to be, the McGill Reporter visited Macdonald Campus to sit down with John Henning, Program Director, Agricultural Economics. At McGill since 1985, Henning currently oversees a program that boasts some 30 undergrads and close to 20 Masters students. In a little under one hour, Henning gave us a crash course in agro-economics, including a quick history lesson in food crises of the past, an overview of the current situation, and an educated look at what the future may hold.

What caused the 2008 food crisis?

It was a bit of a perfect storm with a number of factors coming together at the right – or wrong – time. One of the fundamental factors was that the amount of grain being held in stocks was quite low.

Why are stock levels so important?

These stocks act as a buffer to whatever shocks come around. What we saw happening with the markets was like a little wave. Think about the ocean and you have this wave coming. If you have deep water near the shoreline the wave is no big deal – it rolls into shore and bounces out. But if that wave has a fair amount of energy to it and the water, or the grain stocks in this case, is very shallow, that wave starts building until you have a tsunami. We were already really shallow in stocks and once people started getting the idea that there were going to be shortages, we had that tsunami.

How much is linked to the problems in the financial market?

There has been a definite cross-pollination effect. In early 2007, people started to realize that there was trouble coming in the financial market. By summer 2007, a lot of the hedge funds had woken up and were starting to pull money out of the financial sector in the US. Things started to unravel.

But where were people going to put their money? There had already been some movement upward in agricultural prices starting back in 2006. A lot of commentators were thinking that agriculture was looking good – there were more and more people and supply was not keeping up with the demand. They started piling into commodities.

Over the next few months, hundreds of billions of dollars were invested in commodity markets – not just agriculture, but also gold and metals, as well. But agriculture saw huge flows of money rolling in in what you have to call speculative positions. People were betting on grain prices going up and this was where they were going to make their money.

These market conditions created the first ripples and low grain stocks resulted in the big wave. The analogy is that the hedge funds went surfing on this wave and rode it until July. Then there was a fairly sharp sell-off in agricultural markets.

What caused the sell-off?

Some people have suggested that U.S. monetary authorities acted in a coordinated way to try and trigger this to try to goose the value of the U.S. dollar.

Previous to that people had been abandoning the U.S. dollar to trade in commodities because the prices were going up. Essentially they spooked the market and people started bailing on commodities and jumping back to US dollar finance and this sort of thing. As far as the financial crisis was concerned, it created more liquidity – which was in the interest of the U.S. At the same time, as people started unwinding these bets on corn, rice and wheat and the rest of it and the demand wasn’t there, prices started coming down.

Will we get back to prices of three years ago?

Probably not. There is a long-term trend there. What we saw this year and last year was the market getting ahead of itself – people getting too excited and overly optimistic about pricing and it created a lot of trouble.

Where things end up will depend on how this crop year finishes up, especially in the US. It looks like it will be OK, but it was a little scary there for a while. When Hurricane Ike hit, all the focus was on Galveston and what happened on the coast. But when Ike moved inland and came north it dumped huge amounts of rain through the Midwest and through the corn belt – Iowa, Indiana, Illinois.

I was talking to a colleague of mine yesterday from the University of Illinois and he said right after Ike, you’d see cornfields under a foot of water. More like rice paddies than cornfields. There was some concern about what kind of impact there would be but it doesn’t look like it created too much trouble.

So much of this comes back to how robust the food stocks are?

Yes. If we get more stock rebuilding at the end of this crop year things should stabilize a bit and it would make the system more resilient to any type of adversity next year. We need those stock levels to act as a buffer. But, as I said, I think we’re going to see prices slowly trending upwards.

What kind of impact will the growing financial crisis have on agriculture?

Agriculture is a really capital intensive industry. In Canada there is probably somewhere in the neighborhood of $800,000 per farm on average tied up in the value of farmland, the animals, the machinery – it is a lot of money. We have a lot of diversity in our farms, some of them are very, very small – maybe an acre with not much capital there. But some of the dairy operations have millions and millions of dollars tied up in capital that has to be financed. Obviously, they are very sensitive to what happens in capital markets.

If money starts drying up in terms of lending, agriculture is going to feel it in particular because farmers tend to work on a revolving credit basis. They take out loans in the spring to buy the implements, the seed, the fertilizer and the fuel to get the crops in the ground. Then they wait until the fall, cross their fingers and hopefully get a good crop off and they use the income to pay off the debt.

It is the front end of the crop year where the availability of credit is really important. If that starts becoming scarce, if it becomes difficult to get loans or if the interest rates are going up it will further stress them. If it becomes serious, you’ll get less agricultural output and those stocks won’t rebuild and we’ll be set up for another tsunami.

Are farmers happy about the Bush administration’s bailout bill?

I would say that for most people, the answer is yes and no. Yes, in the hope that it will stabilize things – hoping that the banks will start lending to each other again and we get back to some sort of normalcy.

But the elephant in the room is what will happen to the credibility of the U.S. economy now? There are so many US dollars being held overseas – by China, Japan, Russia – that the Americans are in debt up to their eyeballs to the rest of the world. They’re holding those debts in U.S. dollars.

If the people holding those debts lose confidence in the ability of the US government to pay them back then all hell breaks lose because they will start dumping those assets in fear that if they hold on to them too long they won’t be worth much.

For example, the Chinese are holding a trillion-and-a-half dollars worth of U.S. debt and every day they are watching it go down in value. At some point they may decide they can no longer hold it and turn around and flog it for whatever they can get. That will mean real fireworks.

So, yes, the bailout will stabilize things but people have to pray that the creditors to the US economy will sit tight and won’t dump their assets.

How realistic a scenario is that?

It is entirely speculative. I tell students that this is all based on faith, like a religion. It is the Church of the Presumptuous Assumption because followers believe that the government will always come through.

But what is going on with banks is a problem of faith. They are worried about lending money to each other because they’ve lost faith that they will get it back.

Then there is the government, which has always been the lender of last resort. If people lose faith in the government then there’s nothing to prop it up. Everything comes tumbling down.

We’ve got this faith-based system with Ben Bernanke (Chairman of the Board of the US Federal Reserve) and the other priests trying to calm things down. But if the congregation losses faith in the priests, we’re dead.

No one can predict what will happen because it is all happening in people’s heads. You have to speculate. You can see rationale for some people pulling the plug and rationale for others not pulling the plug. They don’t want to trigger this big tidal wave. It’s a real dilemma. Do I hold on or do I dump now? The expected payoff is probably better to sell off now. Be the first out the door rather than the last. Of course, if you get too many people thinking like that, they can trigger something very large.

The world went through similar crisis in 1970s with rice. Is this type of thing cyclical or are both events entirely unrelated?

They are unrelated. In the 1960s, we had an opposite problem that was bad for farmers – prices were lousy and we had tons of stocks. Low prices and overproduction meant hard times for farmers. Americans, Canadians, Europeans, Australians – everyone was trying to put the brakes on production because they knew if they could scale back production somewhat they could get better prices.

The Americans introduced what they called “set-aside payments” as a policy instrument basically paying farmers not to farm. They paid farmers to take some of their land out of production – the idea being that it was in the common good to take that land out of production. Yes, it looked bad from a public relations standpoint to pay someone not to work but it was for the greater good. We did things like that, Europeans did things like that and, as a result, production started coming down.

This was just in advance of the first oil embargo. Oil prices went up and it made things even more difficult for farmers because they were paying a lot more for their fuel.Then there was a policy change in the Soviet Union. They had always been active in the grain market but not a big player. Typically, if they had a short year they absorbed that internally – people just didn’t have a lot to eat.

In the early 1970s they decided they could take advantage of the situation. Grain prices were low and they had had a short crop. Everyone was expecting them to import a little more but no big deal. At the time there were five really big exporters who controlled most of the world trade in grains.

The Russians basically called them and whispered in their ear “Hey, have we got a deal for you. We need to buy another million tons of corn – but don’t tell anybody – and we want to buy it all from you.” And they called up the next one and struck the same deal. They lined up several million tons of grain, fixed the prices at very good levels before anybody could figure out what was going on. It became known as the Great Grain Robbery. The Russians have always been really good traders and business people and they knew how to use the system. They were locking up supplies. The suppliers were willing to commit at favorable prices but once the market got wind of this – that several million tons of grain had just disappeared – the prices spiked. That spike took several years to work through. By the late 1970s prices were fairly low again. One of the lessons is, when you get a shock like that it does take a few years for the market to settle down.

Can we safeguard against this type of situation?

I think governments are fairly reluctant to get too involved. Partly because the mentality of governments is much more oriented toward a free market than it was 30 years ago. Things like this were attempted years ago. There were specific commodity agreements among countries to build up international stockpiles but they never worked very well.

Philosophically, we live in a world that is much more free market oriented. It just wouldn’t fit the way things have evolved with the World Trade Organization. It has been active in the post WWII era in getting governments not to intervene and letting the market work.

But we’re seeing that this system can also have its own problems. I guess the question then becomes, what sorts of interventions could help? Is there anything that could be done? I think many people would argue that the most important thing would be increased transparency – more information on who’s doing what.

There has been some people suggesting that increasing interest in biofuels has helped drive grain prices higher. Is the need for ethanol at fault here?

It is a factor, but I don’t see it as a major contributor. At least twice as much grain goes into feeding livestock as is used to make ethanol. But sometimes people only look at the front-end use of corn going into an ethanol plant. Like a cow, there is always something coming out the other end. If you put a ton of corn into a plant, you don’t use the entire ton to make ethanol. They really only use the starch and the residual product is fed to animals – it is called distillers dried grains and it is relatively high in protein.

Even if we only look at what comes in the front door of an ethanol plant, it really isn’t a huge amount. I think there is some concern for the future in terms of how many ethanol plants will be built and how large that consumption might get but right now I wouldn’t point a finger at that and say “That’s the cause of higher prices.” It was just one ripple.

With grain prices where they are, the ethanol industry is really in dire straights right now. The ethanol companies that are traded publicly, their share values are fraction of what they were. Some of them are trading around a dollar when they were trading around 13 or 14 dollars a year ago. I recently read somewhere that today someone could buy an ethanol facility for significantly less than what it would cost to build a new one.

The anticipation is that there will be some survivors and they’ll be picking up assets – a bit like we’ve seen happen with the banks and the creation of these super banks.

What can regular people do to help the situation?

The bottom line is, if we all really wanted to do something we’d cut back on meat consumption. Collectively in North America, we are overeating meat. I think the average is about 100 kilos of meat per person per year. Remember, that’s just the average. There are a lot of vegetarians out there and a lot of people who don’t eat that much. That means there are a lot of big-time carnivores out there. And each kilogram of meat is consuming several kilograms of grain so it isn’t a great conversion. Depending on what animal we’re talking about, the ratio can be as high as 7 to 1.

If we cut our meat consumption in half, which wouldn’t be a bad thing health wise, we’d be back to average levels of consumption of the early 1950s.

John Henning’s first job

I come from Niagara Falls and, as you know, the tourist industry is very big there. I worked next door to Marineland at another tourist attraction called the Indian Village. It was a replica of a Six Nations stockade and village.

I hoed weeds and cleaned up litter in the parking lot. Back then, in the 1960s, people littered much more. Since I was the guy picking up all this trash it had a big impact on me. It was a little environment and protecting that environment became very important to me.

One of the things they did was have a show where the native workers would sing and dance. One day, some of them didn’t make it to work. The guy who ran the show came up to me and said “You know all these dances, right?” They found some clothes for me and I became White Owl for the day. [Laughing] I didn’t miss a step.