Two teams of neuroscientists will work together for the first time as part of the transition at the RI-MUHC

By Julie Robert

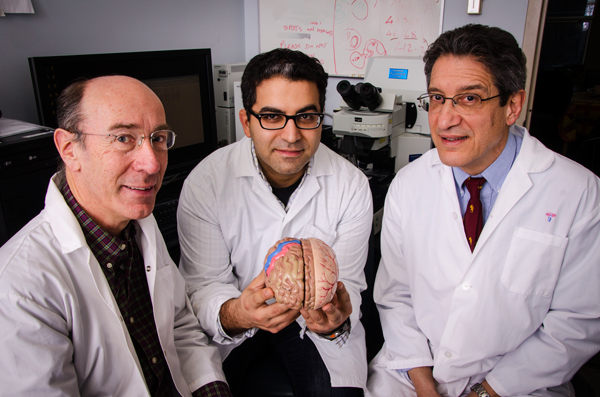

Merging two neuroscience teams who have never worked together can sometimes be almost as complex as the structure of a brain. But this is precisely the objective of a new Montreal General Hospital research program that will focus on brain, vision and brain trauma at the Research Institute of the McGill Univeristy Health Centre (RI-MUHC). This program will unite researchers from the Centre for Research in Neuroscience (CRN) and the McGill Vision Research Centre for the first time. The new merged team will work at unveiling the mysteries of brain wiring to better understand neurodevelopmental disorders such as amblyopia, autism, traumatic brain injury andschizophrenia.

“We focus on the idea that the brain is a very complex computer and that wiring of the elements of this computer is essential to brain function,” explains RI-MUHC neuroscientist, Dr. Salvatore Carbonetto, director of the CRN at the Montreal General Hospital (MGH) and professor of Neurology and Neurosurgery at McGill. “Furthermore, that wiring changes with development, and with experience.”

Figuring out how the brain works is the driving force behind both groups of neuroscientists, but at different levels. One group (CRN) is focused on how neurons communicate via “cellular switches” called synapses and how malfunction of these switches can cause autism and other psychiatric disorders. The other is trying to optimize brain plasticity to reverse disorders that occur in childhood and cause visual loss. The connection between these two levels is necessary to properly understand how the entire system works. One could say it is a match made in the brain!

“This is a very good combination, because the CRN team does a lot of excellent work on synaptic transmission and responses from neurons in animal models, while what we do is really focused on the human side of things, to optimize brain plasticity to recover vision later in life,” explains Director of the McGill Vision Research Centre Dr. Robert Hess. “We add the human side to their fundamental work and that will allow much greater translation into clinical therapies.”

The CRN group has a long standing interest in trauma. Some of the researchers are studying the cellular and molecular events that occur during the neuro-regeneration process, with the aim of developing therapeutics that are now being tested. According to Dr. Carbonetto, the gap between this very basic research and the clinic will be bridged thanks to the tremendous potential of studies on clinical neuroplasticity.

Dr. Hess is studying amblyopia, also known as lazy eye syndrome, which is caused by a defect in wiring between neurons. He hopes this transition will be an opportunity to look at the changes in synaptic transmission relevant to lazy eye that will lead to the development of new treatment approaches.

The merged team will form the tightest concentration of fundamental neuroscientist researchers in a hospital setting, according to Dr. Reza Farivar, member of the McGill Vision Research Centre and scientific director of MGH Traumatic Brain Injury Program, who specializes in traumatic brain injury research. “If you had put cardiologists next to us, we wouldn’t talk much because we do not have much to talk about. But between the CRN and us there is a lot to discuss,’’ says Dr. Farivar, who is enthusiastic about the merger. “A new synergy will be created that pretty much does not exist anywhere else.”

In the spring, this new group of neuroscientists will meet to initiate efforts to combine forces and develop new opportunities for team grants all of which will make the program one of the major research strengths of the MGH.