McGill University has created the Provost’s Faculty Mentorship Network to assist newer, pre-tenure professors gain insights and coaching as they build their lives and careers at McGill.

Launched at the end of summer 2021, the Network pairs experienced McGill professors with junior members of the McGill faculty to counsel them on a wide range of issues – everything from managing their teaching and research careers to achieving work-life balance.

More than three dozen mentees have already been paired with mentors, with more applicants soon to be matched with their new mentors.

Such a wide-ranging mentorship program has been signaled as a need at McGill for at least a decade. A 2011 report from the Principal’s Task Force on Diversity, Excellence, and Community Engagement recommended that the University “demonstrate a firm commitment to the recruitment, retention and professional development of diverse and excellent academic staff, administrative and support staff, and students.”

Another report, from the ad hoc Working Group on Systemic Discrimination in 2016, suggested some tenure-track faculty members had raised concerns about systemic discrimination and institutional barriers as obstacles to their getting ahead at McGill.

Angela Campbell, Associate Provost (Equity and Academic Policies), is delighted that McGill has launched this initiative, which she hopes will go an important distance in addressing the needs of pre-tenure colleagues. She says the mentorship program is open to all junior faculty members at McGill, but believes that the program will yield a disproportionate benefits for members of underrepresented groups and colleagues who join McGill without established contacts or roots at McGill.

“The research suggests that mentorship programs can yield a particularly important benefit for faculty who are women or racialized persons,” Campbell says. “All are welcome to take part in our program – it is universally accessible – and at the same time we hope it will further our larger EDI goals.”

Those recruited to be mentors for the program spent the past year undergoing training – in the middle of a pandemic – which involved virtually meeting with experts to deal with the finer points of how to be a mentor, and how to answer questions which may arise from mentees.

A lifeline for those from underrepresented groups

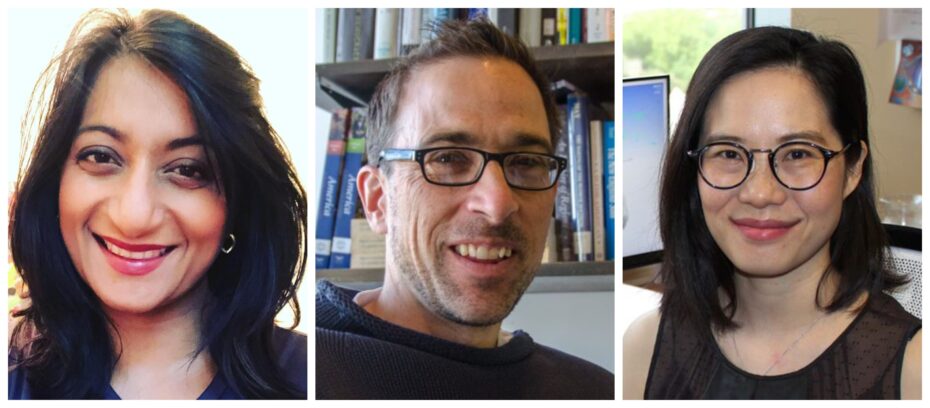

One of the mentors, Natasha Rajah a full professor in the Department of Psychiatry and a researcher at the Douglas Research Centre, says the program can serve as a lifeline for those professors from minority backgrounds.

“Individuals that come from underrepresented groups, who may not have the historical knowledge within their families, or within their networks, about how academia works,” she says. “Having that mentorship may really benefit them. Mentorship intersects with EDI [equity, diversity and inclusion], because individuals that need the help the most benefit the most, I think, from these types of mentorship programs.”

Xinyu Dong, an assistant professor in East Asian Studies who’s been at McGill since 2018, says she signed on to become a mentee to better find her way in a new environment.

“As a minority and twice an immigrant (from China to the US and now to Canada), I also feel especially uprooted and simply wish to find a supportive community,” her application reads.

Many of those who became mentors as part of the Provost’s Faculty Mentorship Network have themselves benefited from some kind of mentoring. Jason Opal, an associate professor of History and Classical Studies, is one of the mentors taking part in the program. He says he has received some mentoring on an informal basis.

“It was crucial,” he says. “I had mentorship from my graduate advisor who kept helping me, and from a new colleague at where I was teaching who would give me specific information that you otherwise can’t find, and would help me to see the big picture.”

Setting personal and career goals

Another mentor, Nicole Li-Jessen from the School of Communication Sciences and Disorders, says when she joined McGill in 2014, she received mentorship from a senior colleague to help her guide her through her new life in Montreal. Later, through a program called Telemachus in the Faculty of Medicine & Health Sciences – which she remains involved with as part of its Steering Committee – she received greater guidance in a wider range of areas, including “time management, how to set your priority to meet your career goals and personal goals.” Li-Jessen says that Telemachus also helped her gain clarity about the tenure process expectations specific to her discipline. The constructive guidance she received made her want to pay it forward by becoming a mentor in the Provost’s Network.

“Being able to build a community of support is very important for junior faculty,” she says.

Opal says this formal mentorship program has a couple of distinct advantages over an informal one.

“The first is that you cannot have someone from your department [as your mentor],” he says. “They’re more able to give good advice based on being external. So [as a mentor] you’re more external, you’re more third party, you’re more impartial. The other benefit is the training we had about things like the nature of disclosures, the nature of more difficult problems, that kind of like I won’t say legal, but more the kind of official relationships that happen in universities. Informal mentors don’t do that.”

A model for mentorship

Blane Harvey, an assistant professor with the Faculty of Education, says he got involved with the program to learn more about the mentorship process itself.

“I wanted to learn how to manage this different approach to mentoring my own students, and I found it overwhelming trying to figure out, to just learn as I go without strong guidance,” he says.

Harvey also recently became a father, and he felt he needed some additional help with managing his career and fatherhood at the same time.

“About six months ago, I had a daughter, and something that became very apparent to me is that work-life balance needs to be rethought when you become a parent.”

Rajah says in general, expectations for newer professors are far greater than when she arrived at McGIll a decade and a half ago.

“Things have become really competitive,” Rajah says. “I feel like [new profs today] are more burdened than maybe their more senior colleagues were when they were at that stage. Now you do two postdocs to get an academic position. And often that means you’re older, that means you usually have a family. And so, this vision of, you go to graduate school single, and you stay single, and… that vision isn’t real anymore. And it was definitely biased to a certain group.”

Both the mentors and mentees agree that pairing people from different disciplines can have its advantages. Li-Jessen, for instance, has a mentee in the Finance department. Although their academic disciplines are very different, their mentor-mentee profiles overlapped in the areas of EDI and navigating the tenure process.

“I’m sure that there will be some new synergy,” Li-Jessen says. “Maybe we’ll also do some research together! You never know.”

“I think there’s a lot of value in this idea of mentoring people that are actually coming from quite different backgrounds,” Harvey says. “We often think that you should mentor somebody in your own discipline, because they know what’s expected in your field. But actually we can draw a lot of inspiration from learning from people who work in very different ways from us. That’s really how we can innovate and how we can move forward. So, I think this particular initiative is cool for doing that, which is not necessarily what mentorship looks like, a lot of the time.”